A small mountain stands in the middle of the ocean, a hill, strictly speaking. It is called Anak Krakatau, which roughly means “Child of Krakatau”, because a much larger mountain once stood in its place. Just like its predecessor, the Anak Krakatau can spit fire because it’s a volcano. Whenever it erupts and the lava flows down its flanks into the sea and the rocks it throws into the air collect on its banks, it grows a little higher and further into the sea.

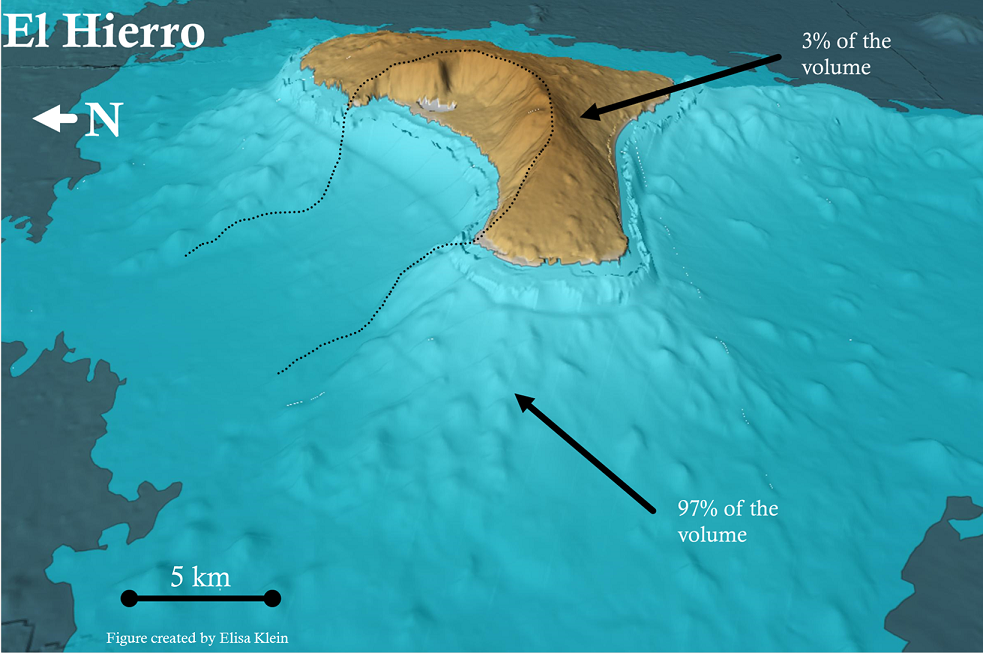

Just like an iceberg, only the smallest tip is visible above the water.

If you look under the sea surface, you can see that the “volcano child” is not as small as one might have thought at first. Because just like an iceberg, only the smallest tip is visible above the ocean. If such a volcanic island continues to grow, various circumstances can cause it to become instable, similar to a sandcastle that you piled up too high. Sometimes a large part of the volcano slides very slowly, a few centimeters a year. But sometimes it gets a lot more dramatic and a whole flank collapses into the sea in a single fast event.

If you drop a stone into the water, it causes the water to move and creates small waves. When half a volcano slides into the ocean, the exact same thing happens, only on a bigger scale: A tsunami develops. This is exactly what happened a few years ago at Christmas on Anak Krakatau. A large block from the small volcano slid into the ocean, causing a tsunami that killed several hundred people on the surrounding islands.

Under which circumstances do volcanic islands collapse catastrophically and when are they more likely to be stable?

Tsunamis that are triggered by earthquakes can usually be predicted well today and people can be warned in good time. With tsunamis triggered by landslides and collapsing volcanic islands, this is much more difficult. The problem is that it is not well understood what happens when a flank collapses into the ocean. There are many open questions; Under what circumstances do volcanic islands collapse catastrophically and when are they more likely to be stable? Is there a connection between the slow sliding of some volcanoes and their collapse? Is the gliding even the beginning, a warning of a catastrophic landslide?

For my PhD, I’m looking at the geometric shape of volcanic islands. It is important that I look at the entire volcanic structure – from the sea floor to the summit. I look at so-called DEM data for this. DEM stands for Digital Elevation Model, i.e. digital height maps. On land, these are obtained through very precise radar measurements from satellites and can be downloaded from data platforms on the Internet. However, radar waves cannot penetrate water, which is why so-called echo sounders are needed to survey the ocean. These are devices that are attached to the hull of a ship and emit a sound signal. The device then listens for the echo from the signal. It can then calculate the depth to the sea floor from the time it takes for the echo to get back to the ship.

So far, only a small part of the oceans has been mapped.

This data can also be found on special data platforms, but so far only a small part of the oceans has been mapped in this way. If I can find a good data set, I can determine where the base of the volcano is, where it ends and where the sea floor begins. I use a program I created to help me with this. Then I can calculate a lot of properties. How steep are the slopes? What is the area and volume, and how much of it is visible above the water?

I collect all this information in a database for all the volcanoes I study. I also gather any additional information I find in scientific publications; How old the volcano is, what material it is made of and whether it has already collapsed. I can then take a very close look at the database and find connections with the help of statistical methods. Perhaps very large or very steep volcanoes collapsed particularly frequently?

Of course, I can’t stop volcanoes from collapsing with the answers to these questions, and I don’t think anyone will ever be able to do that. So, I wouldn’t have been able to save Anak Krakatau either. But each of these answers help us to understand a little better why volcanoes sometimes creep slowly into the sea and sometimes collapse into the water rather dramatically. The more we know about this, the better we can assess the dangers and how best to protect people from them.

Elisa Klein

Find me here:

Pre-Collapse Website

Twitter: @Elisa_Klein_

And on Research Gate