By the time this blog entry is published, I will have completed my first year as a doctoral candidate at GEOMAR. And what a year it was! As a university student I heard all the stories, I read all the memes and saw all the videos on #PhDLife. I thought I knew what I was getting myself into and that I was prepared and ready. I was very wrong! I think the video The five stages of a doctoral thesis by the German YouTube channel The secret life of scientists covers it perfectly. The “naïve starting phase”, where you are confident and excited, because you just finished your Master’s thesis, your first real science project, is followed by the stage of disillusionment:

“You realize quickly that everything you learned during your Master’s thesis is irrelevant now. It also occurs to you that while in theory you learned a great deal at University, you have absolutely no idea how to do things in practice.” [1]

This! Very much this!

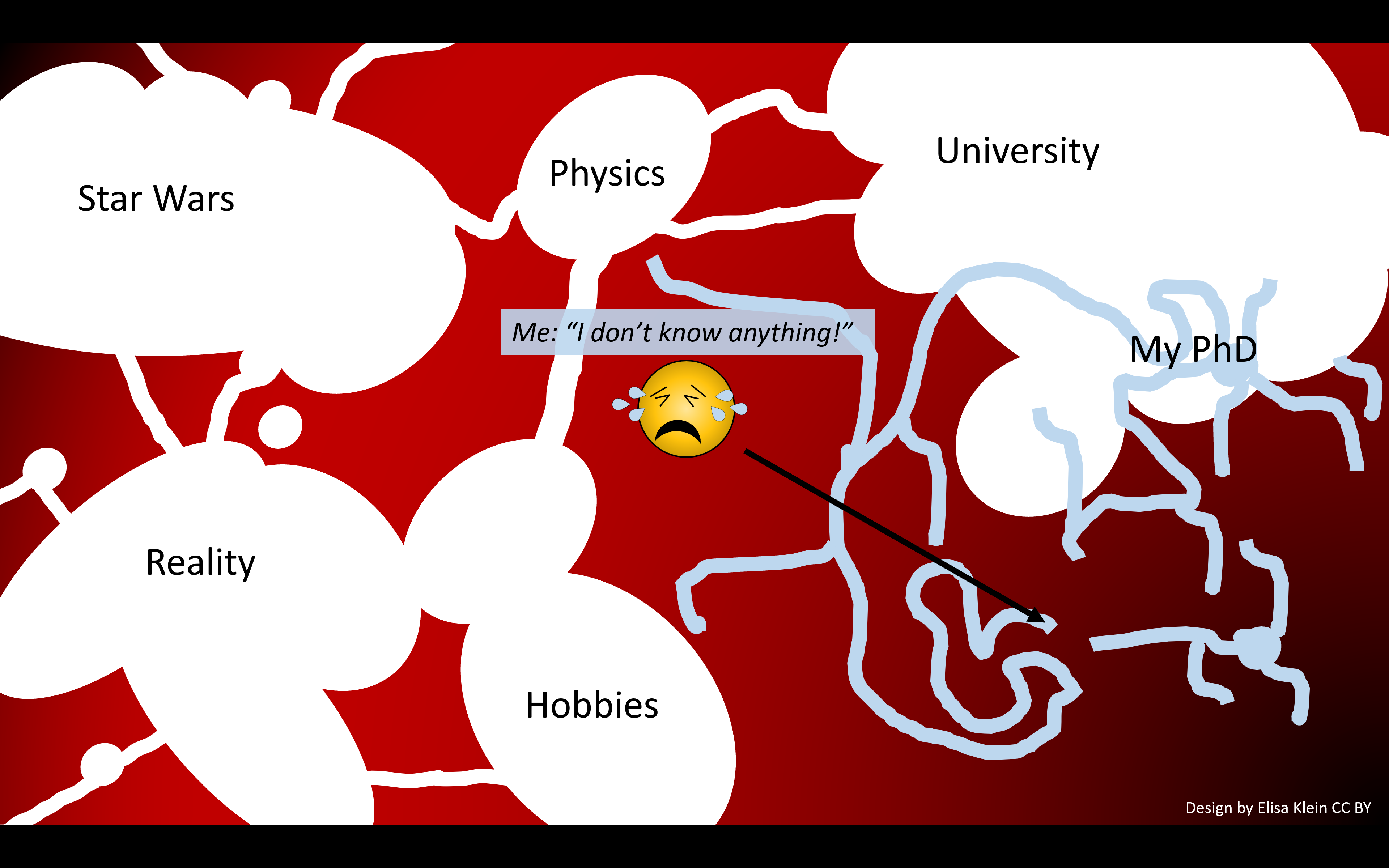

For me, the disillusionment stage consisted of a single main struggle: Being utterly lost as to where I as a scientist and my research fit into the big picture of science. This threw me into what I call a scientific identity crisis.

A part of this crisis was self-inflicted, as I chose to change the method, though not the subject of my research, when starting the PhD. I am very much a generalist, which, for a long time I thought was a disadvantage. It was during my Bachelor thesis that I realized that all my weird disconnected interests and skills become a useful package in science. Where else can you combine using a foreign language, math and physics skills, writing, creating aesthetically pleasing, yet informative figures and a constant curious stream of adult-annoying questions to your advantage? So, the burning question for me was not “Am I a scientist?”, even if I struggled this year, I never questioned that. But rather “What kind of a scientist do I want to be?”.

I found that I cannot compete with my science friends who left University highly specialized in one method or being fluent in a bunch of programming languages. That’s not me! I am genuinely interested in the themes I have been working on, but when I was done with my Master’s thesis, the prospect of doing that method again and again seemed daunting and, quite frankly, boring. However, there is a great disadvantage in changing the method or the field: You have to learn to work with a new set of software, which takes time. I was constantly frustrated by being held back by my lack of software skills, while from a geophysical point of view I had a very clear picture of what I wanted to do with my data. I just needed to figure out how it worked with that software. I have the most supportive supervisor, but she couldn’t help me much in this regard, as she wasn’t familiar with the software either and it took me a few months to find people whom I could ask (besides, you know, Google and YouTube).

The search for a network was so difficult because I didn’t really have an idea what to search for. I didn’t have the necessary vocabulary and definitions. My work didn’t have a name yet. It was like being set out into a hazy, foggy forest and being told to go North. You run around in circles, mark where you have been and try to find clues on which way to go. Or perhaps you even stumble across an established path, that is actually leading somewhere. Slowly but surely, I made some progress. I found papers and people and a name for the field. I began to see connections to related research topics and establish where I and my work fit into the bigger picture. As if the fog was slowly fading, and suddenly recognizable features appeared in the distance.

In December I had a very bad phase. I was immobilized by imposter syndrome, self-doubt and utterly overwhelmed and stressed out by having to be a self-reliant adult in this world. A lot of things came together at the time, not the least of which were raising Covid numbers. However, I also participated in a seminar on science communication and that really kept me afloat. I realized that my intrinsic motivation for doing science is exactly this: Sharing my passion and fascination for it with people and giving insights into the world of academia. So, here I am, sharing my struggles on this blog. And if somebody asks me today “What kind of a scientist are you?” I can proudly answer: “The heck do I know!”

Elisa Klein

[1] Translated from German by the author.

Link to the video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NgUATs2bx7w

Find me here:

Pre-Collapse Website

Twitter: @Elisa_Klein_

And on Research Gate

Despite not being a doctoral candidate (yet?) I relate to your post on so many levels – most of all your feelings about being a generalist in a world of highly specialized scientists! Thank you so much for this very well written post and your honesty to share these feelings publicly,I enjoyed reading it a lot.

Thank you! I have heard about more and more career paths recently and I am slowly realizing that a lot of “specialists” have come to that place in a very convoluted way. So, there are probably more generalists out there in academia than we think 😉