Ahoi!

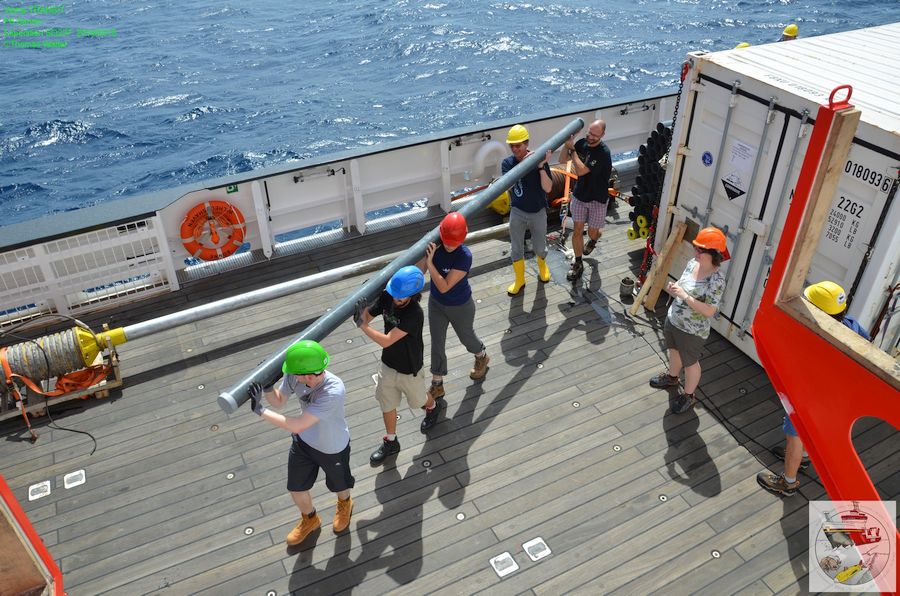

Ein wunderschöner Sonnen-Tag bei 10° Nördliche Breite. Heute habe ich etwas Zeit meinen Blogeintrag zu schreiben, da unser Bathymetrie Team die nächsten beiden Tage die Vema Transformstörung weiter kartiert. Mein Name ist Christopher Schmidt und ich bin hier an Bord für das Schwerelot verantwortlich. Das Schwerelot ist eine 5 Meter lange Metallröhre, an dessen oberen Ende ein Gewicht von 1,3 Tonnen angebracht ist. In dieser Röhre ist ein weiteres Plastikrohr, in dem wir versuchen Sedimentproben aus der Tiefsee an die Oberfläche zu bringen. Dafür wird das Schwerelot über die Bordwand gehievt und an einem Kabel 5000 Meter in die Tiefe gelassen, bis das Gewicht die Röhren ins Sediment drückt. Ein Kernfänger am unteren Ende des Rohres verschließt das Schwerelot und das gewonnene Sediment wird an Bord gehievt. Sedimentkerne aus diesen Tiefen bestehen zumeist aus Schluff und Tonpartikeln. Das sind alles sehr, sehr kleine Minerale, die durch Strömungen und Wind von den Kontinenten in die Ozeane getragen werden oder von im Ozean lebenden Organismen stammen. Der Zwischenraum in den Sedimenten ist gefüllt mit sogenanntem Porenwasser und ich interessiere mich für dessen chemische Zusammensetzung.

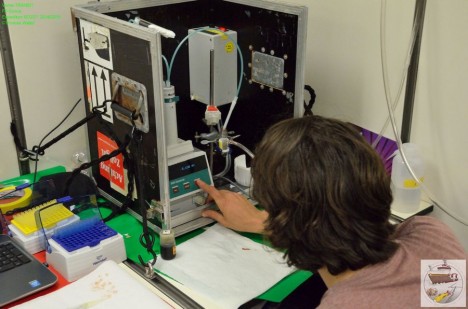

Die Vema Transformstörung ist eine große, alte Verwerfung im Meeresboden, die vielleicht als Wegsamkeit für Fluide aus den darunter liegenden Gesteinsformationen dient. Wenn diese Fluide aufsteigen, verändern sie die Zusammensetzung des Porenwassers zwischen den vielen kleinen Partikeln. Das Porenwasser gewinnen wir mittels Spritzen mit kleinen Filtern, den Rhizonen, aus dem Sedimentkern im Plastikrohr. Die gewonnenen Wasserproben werden dann hinsichtlich ihrer Geochemie untersucht, um Hinweise auf aufsteigende Fluide zu finden. Hier an Bord wird direkt die Alkalität titriert, die restliche Chemie wird zu Hause in Kiel bestimmt.

Außerdem bohre ich den Kern auf und entnehme Sedimentproben für andere Arbeitsgruppen. Die Stratigraphie (also die Schichtung) des Kerns und die Sedimentzusammensetzung verrät diesen Wissenschaftler etwas über Veränderungen in Ozeanströmungen und Klimaschwankungen.

Jetzt genieße ich nochmal einen Sonnenuntergang an Bord, bevor in zwei Tagen wieder die Stationsarbeit beginnt.

Christopher Schmidt, Masterstudent, Geomar Kiel

[English]

Greetings!

It’s another lovely day at 11°N and I’ve got some time to write my blog entry today as we’re currently carrying out a multibeam survey before the next sampling station in 2 days. My name is Chris Schmidt, I’m a master’s student in Geology at Kiel University and I am responsible for the gravity corer onboard. The gravity corer is a 5 m long, hollow metal tube with a big 1.3 ton weight on top. The gravity corer is lowered over the side of the ship on a cable and when it hits the seafloor the tube is driven into the soft sediments by the weight. The corer is then hauled back up to the ship and it brings with it a section of the sediments it sampled inside the tube. Seafloor sediments tend to be muds or clays. This means they are composed of lots of very, very small mineral particles that have travelled into the oceans from the continents – through rivers or by the wind – or are produced by the animals and plants that live in the ocean waters. We are very far from the continents so most of the particles are very fine, but as we get closer to big landmasses they get larger and then they are usually called sands, just like on the beaches at home. Between these particles are lots of tiny spaces filled with seawater. We call this the pore-water and I am very interested in it’s composition. The VEMA transform is a big, old crack in the seafloor and it my act as a pathway for fluids from the deeper rocky crust to get back into the ocean. If these fluids are coming up underneath the sediments we sample they change the chemistry of the pore-waters and give us clues as to the location and extents of these fluid “vents”. On board I examine the alkalinity of this water and I’ll do further analyses back home in Kiel.

Other people will also use samples from the gravity corer so I’m also taking samples of the sediments for them. Gravity core samples can provide information on the stratigraphy (the layers) in the sediments, which may provide information on the history of the oceans and climate. For example, in other places similar cores are used to examine the history of volcanic eruptions from ash layers and to constrain anthropogenic climate Change.

Christopher Schmidt, Masterstudent, Geomar Kiel

Das Schwerelot wird über die Bordwand gehievt / Gravity corer is lowered over the side of the ship. ©Thomas Walter

Das Schwerelot kommt mit Sediment zurück an Bord/ Gravity Corer is hauled back on board. ©Thomas Walter