Wie aus einem Eimer Schlamm eine wissenschaftliche Probe wird

Ich stehe im kältesten Raum des Forschungsschiffes Sonne bei -20 °C. Irgendwie fühle ich mich mehr wie auf einer Polarexpedition so dick eingepackt in Winterjacke und mit meinen Handschuhen. Vor mir auf dem Metallregal stehen diverse Rotdeckeltonnen gefüllt mit Schlamm aus der Tiefsee, gelöst in hochprozentigem Ethanol. Obwohl ich Handschuhe trage, durchdringt die Kälte meine Hände, die sich fast so kalt anfühlen wie die Rotdeckeltonne, die ich im Arm halte. Ich halte die Rotdeckeltonne wie ein Baby und rolle sie langsam hin und her. Dabei durchmischt sich der Schlamm aus der Tiefe mit dem Ethanol. Das regelmäßige Rollen alle drei Stunden nach der Erstfixierung verhindert das Festfrieren des im Schlamm gehaltenen Wassers und verbessert die Qualität der Fixierung. Nach 12 Stunden tausche ich den Ethanol aus, um das restliche Wasser aus der Probe zu bekommen. Durch eine Konzentrationsmessung nach 24 Stunden kann ich dann kontrollieren ob der Ethanolgehalt über 90 % liegt. Eine kontinuierliche Kühlkette bis hin zum Sortieren auf Eis und ein hoher Ethanolgehalt sind die wichtigsten Faktoren für eine hohe Probenqualität und um DNA von den Tierchen aus der Tiefsee zu bekommen, die im (Infauna) und auf dem (Epifauna) Meeresboden leben. Eigentlich kein Wunder, da es am Meeresboden in 5500m Tiefe gerade mal 2 °C Grad warm ist.

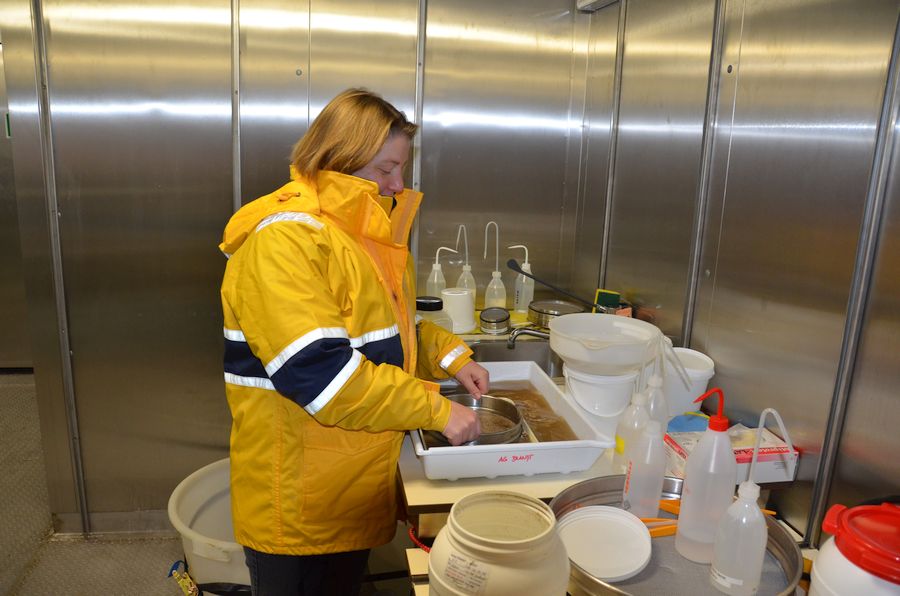

Die Geschichte meines Eimers voll mit Schlamm beginnt am Meeresboden während der EBS (Epibenthosschlitten) hinter dem Schiff hergezogen wird. Sobald das Gerät wieder an Deck ist warten bereits 2 große Eimer mit vorgekühltem und gefiltertem Seewasser darauf mit dem Schlamm aus den Netzbechern gefüllt zu werden. Solange der EBS in der Wassersäule hängt umschließen Kühlboxen die Netzbecher und transportieren das kalte Tiefenwasser mit an Deck. Wenn die Boxen geöffnet werden, kommen die Netzbecher sofort in die Eimer (einen für den Netzbecher vom Supranetz, den zweiten für den Netzbecher vom Epinetz). Mein Job ist es zusammen mit Ulrike Minzlaff die beiden Eimer so schnell wie möglich in den Kühlraum zu bringen, wo wir bei 4 °C die Proben waschen und bereits größere Tierchen für biochemische Analysen herauspicken. Um zu gewährleisten, dass uns genügend gefiltertes Seewasser im Kühlraum zur Verfügung steht, hieß es erst einmal Eimer schleppen. Insgesamt mussten wir 16 Eimer filtern und vorkühlen und vom blauen Deck ins grüne Deck herunterbringen. In diesem Fall ist Wissenschaft auch Sport und trainiert unsere Armmuskeln. Unten im Kühlraum stößt Ann-Christine Zinkann zu unserem Team. Ulrike und Ann arbeiten an ihrer Master-, bzw. Doktorarbeit. Zu dritt stecken wir die Köpfe zusammen, um die größere Tierchen zu erspähen bevor wir den Schlamm in vorgekühlten 96 %igen Ethanol überführen.

Jetzt, 48 Stunden später, ist die Probe durchfixiert und fertig zum Sortieren. Noch immer im Kühlraum fange ich an zu frösteln und stelle die Probe auf ein Tablett mit Eis, um sie nach oben zu transportieren. Ich verlasse den -20 °C Raum durch die dicke Eisentür und durchquere den 4 °C Raum. Kaum öffne ich die zweite dicke Eisentür kommt mir warme Luft entgegen. Ich betrete den Gang auf dem grünen Deck und schließe die Kälte wieder im Kühlraum ein, mache mein Kreuz auf der Probenliste und klemme mir die Schale mit Eis und Probe unter den Arm. Der andere Arm ist frei, damit ich mich auf der Treppe nach oben notfalls stabilisieren kann falls die Schiffsbewegung mich aus dem Gleichgewicht bringen sollte. Kaum im Nasslabor II, unserem Sortierlabor, angekommen, stelle ich die Probe auf dem Tisch ab und schäle mich aus meinen warmen Sachen zurück in den Sommer. Die erste wird vom Team bereits sehnsüchtig erwartet. Die Wartezeit von 48 Stunden ist für die von Natur aus neugierige Spezies „Wissenschaftler“ eine Geduldsübung. Jetzt ist es soweit: der Eimer voll Schlamm hat seine Metamorphose zur wissenschaftlichen Probe abgeschlossen!

Dr. Saskia Brix, Senckenberg am Meer, Deutsches Zentrum für Marine Biodiversitätsforschung (DZMB)

[English]

How a bucket of mud becomes a scientific sample

I am standing in the coolest room of RV Sonne, the cooling room at -20 °C. In a way, I feel like on a polar expedition wearing a winter jacket and gloves. In front of me in a milky light a few icicles are hanging from the metal shelves which are occupied by huge sample jars. Although I am wearing gloves, the sample jar is freezing cold and my hands are starting to be cold only after a few minutes holding it. The jar contains 6 Liters of extraordinary mud – mud from the deep sea and full of critters living down there. I am holding the jar like a baby gently rolling it in my arms and trying to elute the sediment (mud) inside as good as possible in ethanol. This job needs to be done every 3 hours after the sample came up with the EBS (epibenthic sledge) from 5500 m depth. After 12 hours I am exchanging the ethanol to ensure a complete fixation for further work including winning DNA out of the critters of the deep. After 24 hours we measure the ethanol concentration to ensure over 90 % ethanol in the sample. Cold temperatures and high ethanol concentration are most important for retrieving high quality DNA from deep-sea crustaceans, which are not visible by eye and live in the sediment (Infauna) or on it (Epifauna). When the sample is coming up from the deep sea (it is about 2 °C down there…) it needs to stay cold the whole time until we start to pick the deep-sea critters out of the mud 48 hours later when the fixation process is done.

The history of the buckets of mud starts 48 hours earlier when the EBS was back on deck after the first deployment. Before a bucket of mud ends on the shelf in the -20 °C room, it was taken from the cod end of the epibenthic sledge and put in precooled and filtered seawater directly on deck next to the EBS to escape and hide from the warm and tropical air. To ensure that enough chilled seawater for washing the mud is down in the cool room, we needed to filter 16 buckets full of seawater and bring them down the stairs from the blue to the green deck. If we would not filter the seawater, we would find planktonic copepods from the surface water all over in our deep-sea sample. Science is also sports in this case and training for our arm muscles carrying all these buckets. Ulrike Minzlaff and me took our two buckets full of mud (one for the cod end of the supranet and one for the cod end of the epinet) to the cooling room. Down there, Ann-Christine Zinkann was with us to wash the sample and pick out living animals we could see by eye before we put the deep-sea mud in chilled 96 % ethanol. Both of them take creatures from the deep for biochemistry analyses for their master and PhD theses.

Standing in the cooling room 48 hours later holding the sample in my arms, I am now starting to feel as cold as my sample. I put the cuddled sample on ice for my way back to the lab. Back through the thick metal door I enter the 4 °C degrees cool room. From here, I make my way to the next thick metal door and end in the ship´s corridor on the green deck. Opening the door warm air is touching my skin and immediately I am happy to be out of the cold. I do my cross on the checking list, already thinking that I need to get rid of my warm winter jacket. One arm around the ice-cold sample, the other arm free to stabilize myself in the ship´s movement I go up the staircase to the blue deck. On my way back to the sorting lab I meet other scientists busily running around in shorts and T-Shirts. As soon as I reach my destination, the wet lab II – our sorting lab – , I put the sample on the middle table and start to open my jacket happy to change from polar dress back to summer style. Seven other scientists are already awaiting the ready-to-be-sorted sample. One habit of a scientist´s nature is to be curious and after 48 hours of waiting for a final fixation process, of course everybody in our team is curious to look at the first sample to be sorted on this scientific maiden cruise of RV Sonne. The bucket of mud standing in a tray full of ice is now a scientific sample, which will hopefully help us to increase our knowledge about life and species diversity in the abyssal plains of the North Atlantic Ocean.

Saskia Brix, PhD

Senckenberg am Meer, Deutsches Zentrum für Marine Biodiversitätsforschung (DZMB)

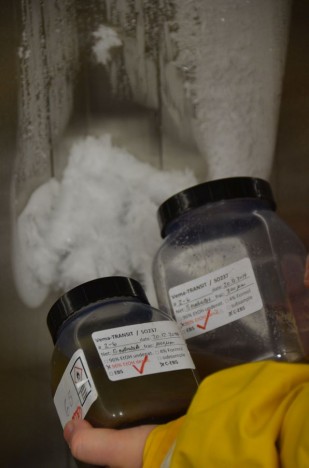

Kautexbehälter der ersten Proben von Station 2-6 in -20 °C / Sample jars from the first sledge deployment, station 2-6 in -20 °C. ©Thomas Walter

Hallo Saskia,

so kalt habe ich es mir auf der MS SONNE(!) nicht vorgestellt. Danke für den wunderbaren Bericht.

Mach(t) es weiter so gut und viel Spass bei der Forschung!

Hamburg ist nun weiß gepudert.

Guten Rutsch in ein fröhliches, gesundes 2015.

Herzlichst

Hilke

ps: bitte grüße Angelika, Thomas und Marina!