Last week, we sat with all our GAME friends together, talking, drinking, having fun and suddenly we had this melancholic thought: “damn only one month to go”! Where did all the time go? How fast can a 9-month experience be? We got a bit sad and started talking about all the great things we experienced, all the nice people we met, all the cute dogs who had accompanied us and all the hard times we had when nothing worked how we wanted it to and we were just there in the middle of our mess thinking `WHY???` (But then, of course, everything did work out and we had a smoothly running experiment and GAME is awesome!).

But let’s start from the beginning. Back in March 2018, Team Chile met for the first time. So, who is Team Chile? Well, we are two very eagerly working bees, with a lot of love for the ocean and all animals on this planet (maybe sometimes a bit too much love). Martín, from Chile, is already an old-stager at GAME, since he already participated in the last project (apparently, he is a workaholic, who cannot get enough of crazy working hours) and Lili, from Germany, who is just in the middle of her bachelor studies. Half-baked and naïve enough to think that she can easily write her bachelor thesis about this project. Hence, the perfect team. Now that we have established that, let’s start talking about actual content. What is GAME, what have we done and how was our time in Chile during the past 6 months.

View of the University Bay at which we spent day and night. In the background are the cities Coquimbo and La Serena.

If you have read the previous blogs, you might be familiar with GAME. If not, here is a short overview. GAME stands for Global Approach by Modular Experiments. Until now, institutes from all over the world participated in the programme and offered laboratories for the students to work in. The experiments are usually realized by teams of two students and ideally one of the team members is from the country the institute is in and the other is German (or is enrolled at a German university). After a six-month period, during which the experiments are conducted, the data are analyzed synoptically by all students from all countries at GEOMAR.

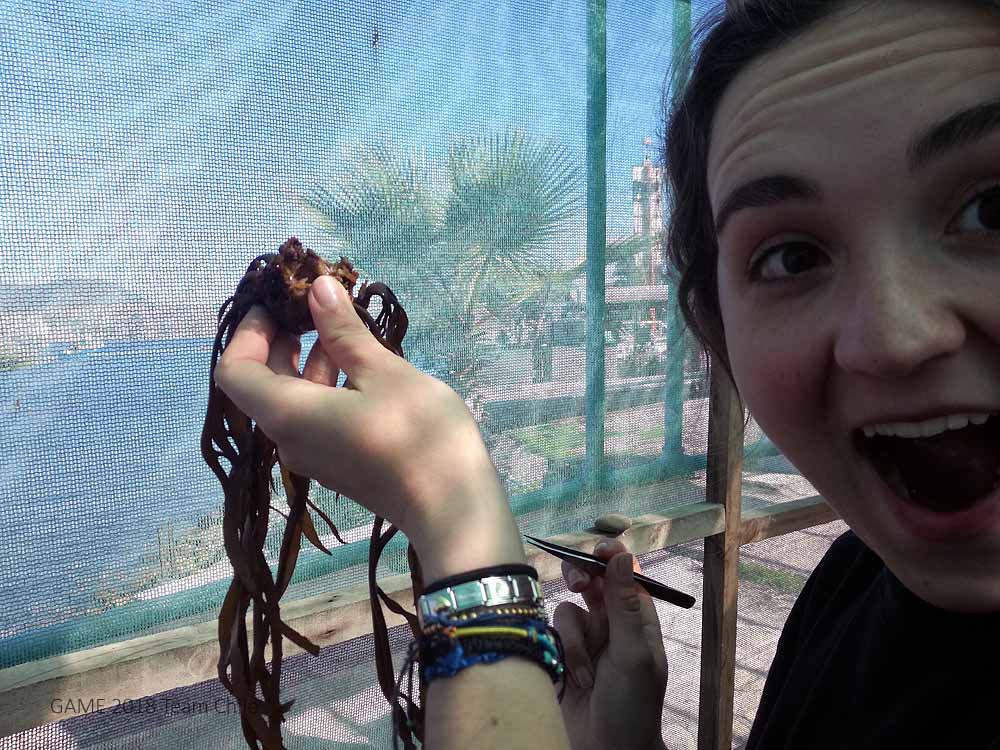

This year’s project was about how marine grazers’ food preference would change with ocean warming. To realize this experiment, we first had to run a couple of small experiments, which made our schedule pretty tight. So, once we both had arrived in Chile, we started right away with the first experiment, which was about finding an adequate marine grazer and algae. Still in the relatively warm months of April and May (autumn in the southern hemisphere) we jumped into the sea just in front of our university, where we could easily find a wide variety of differently colored and shaped algae, as well as a wide range of animals that seemed suitable for our experiments. After several small-scaled feeding experiments, we decided to use the black snail Tegula atra as our companion. This snail is a beautiful medium-sized gal, which, most of the time, did exactly what we wanted it to do: Eat. Unfortunately, the locals have a big culinary interest in our precious snail and at the usual diving spots only few individuals could be found. According to Martín the black snail is particularly tasty and therefore under heavy fishing pressure (although, the tastiness could not be reconfirmed by Lili, as she refused to eat her little new friends). Due to this, we had to drive to either protected areas or rocky shores, to be able to collect enough snails. What was not so bad, because of this Lili could see many super pretty places in Chile (the impressed German, how Martín liked to call her). After we collected enough snails and algae for the experiment and placed these in their new homes, the real fun started.

Chilean landscape near our sampling spot in Lagunillas. Note that the rare red Añañucas are in blossom.

The aim of the first pilot study was to find out, how temperature influences the feeding rate on pelletized algal material. For this, we had to keep 80 snails in the lab and needed to do a manual water exchange twice a day for almost 20 days. This summed up to about 3200 water exchanges! Furthermore, the pelletized algal material needed to be made by hand. In few words, we had to sample, clean, dry and grind the algae to then ‘bake’ the pellets. It was like baking your own bread from wheat grains! In total we made almost 500 pellets. This, sure, was fun and did not feel at all like assembly-line work. After successfully finishing the pilot study, we could then move on to the next step: The main study. In this, we tested whether a temperature increase affects the diet composition of the snail via multiple-choice feeding assays. For these assays, we decided to use five different algae species, which could all be found within the gasoline tank range of Martín’s old jeep. But first, we needed to build a laboratory set-up, in which we could keep all the algae and acclimatize them to rising temperatures. This might sound easy, but, for real, this was not an easy task at all! The heating system constantly broke down and caused smaller or bigger electricity short cuts, the pumps decided, without apparent reason, to stop working and we had quite some flooding in the set-up area. Sounds like fun, right?! Well, it took us almost a whole month to fix all the problems, and only with the help of our dear colleges at the laboratory and our true dog-friend Marcelina, who was always there to cheer us up, we were able to get everything up and running.In the end, however, we were quite proud of our set-up and it (almost) never failed again.

At this time, it was already end of July, which means cold winter in Chile! So, unlike most of the other teams, we were freezing like little cold frogs and still had to go in at 14°C to dive for snails and algae. We were lucky when we could feel our hands and feet after an hour in this freaking-cold water (okay, so mostly Lili was freezing and Martín pretended not to be sooo cold). But now enough of the complaining. At the beginning of every dive, while the limbs were still warm, we could really enjoy Chile’s fantastic underwater world, with pretty sea stars, clumsy crabs and big kelps which were moving with the waves.

Sampling experience in Mineral de Talca. When you look really close, you can see Martín in the very back.

Once we had collected enough snails and algae, we transported them back to the University, placed them in their new homes and started right away with the acclimation period. During this time, we steadily increased the temperature and every day twice we ran and exchanged the water of our dear snails. This was hard work, especially, if you consider that the snails needed our attention every single day! They do not care for holidays nor weekends and so we needed to be there every sacred day, morning and afternoon, taking care of our beloved snails.

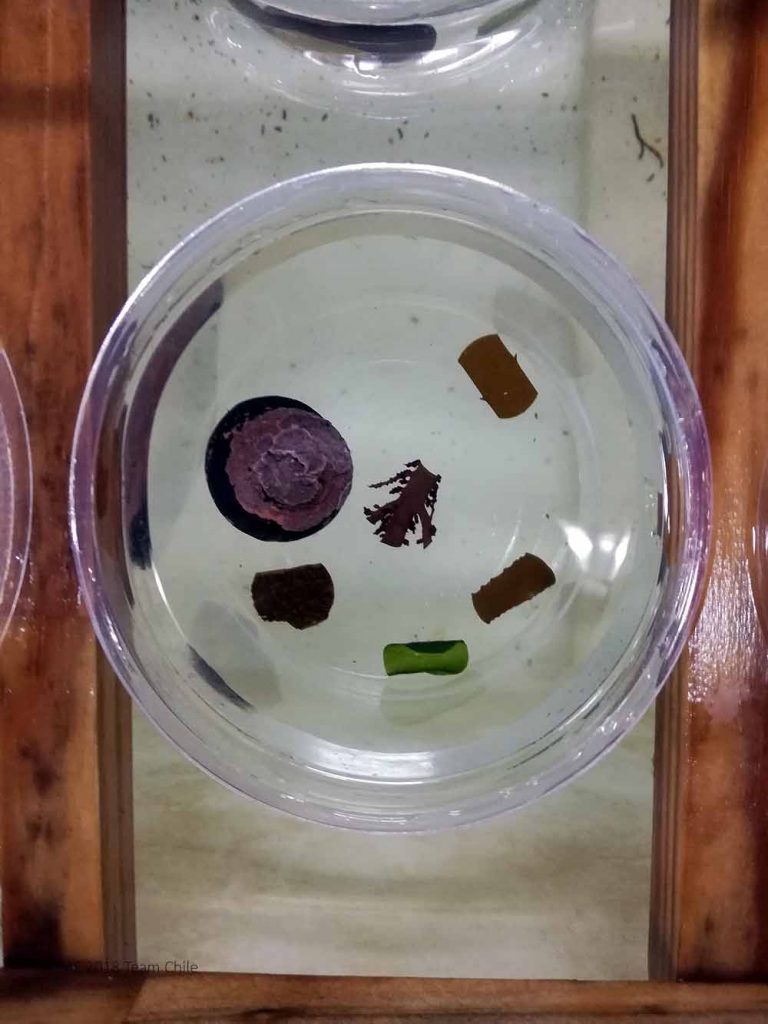

Feeding assay. The big round thing with the pink coat is one of our beautiful snails (Tegula atra) the other things are algae pieces.

Soon the guards at the University entrance knew us and we always got the ‘you poor thing have to work’ – look from them. But we successfully finished the entire main study just one day before the national holiday in Chile! It was the perfect timing to enjoy the different typical Chilean activities and to stuff ourselves with delicious Chilean food. Could not have been better! After the holidays, we spent one more week with cleaning, working and making sure that everything was left as clean and ordered as possible. Then we were already preparing to fly back to Germany! With the heart and luggage loaded with knowledge, good experiences, algae samples, and more than one souvenir.

Now, back in Germany, we met all the other teams, exchanged experiences and stories about our time abroad (or, for the non-German students, the time at home). Especially in the first couple of weeks, we were just talking about how everyone managed to survive, to complete his/her experiments successfully and how grazers and algae behaved in the lab. All the experiences and images from 8 countries were all put together in just one room. However, we also had work to do. First, every team did some analyses only for its data and then we were running the global analysis with everybody’s data in one pot. It is not so easy to come to one conclusion when 16 minds are involved, especially when everybody made some changes to adapt the experiment to the local conditions. So, the comparability between sites was shrinking every time somebody rose his/her hand to say ‘well, we did it a bit different’. But after some heavy thinking and discussions, it now appears like we have it all worked out and that we are ready for the next step. This is presenting our data and being proud of the great experiment we put all our sweat, tears, blood and laughs in!

Cheers,

Lili and Martín