Buenos días from Chile!

Time is passing by so fast – our experiment will be finished in just a few days and soon we will head back to Germany and meet all the other lovely GAMEr’s in Kiel. The past few months have been very salty, stressful and exciting for us and our organisms – but let’s start from the beginning…

After our GAME meeting in March in Germany, we went to Coquimbo, Chile, around mid of Apirl to work at the Campus Guayacán of the Universidad Católica del Norte together as a team. Martín is an undergraduate student of Marine Biology from Coquimbo, who is living in the neighboring city La Serena and who is spending as much of his free time in the water as possible. Nora is a student of the University of Rostock, she is currently doing her Master in Marine Biology and she came to South America for the first time. It is a big help for her to have an English speaking team partner, ‘cause her Spanish skills are about zero (especially in the Chilean Spanish jungle. Maybe you have heard about all the crazy Chileanisms, haha).

#1: The Grazer-Experiment

During our first week we started the pilot studies with our test organisms: the red sea urchin (Loxechinus albus) and the black sea urchin (Tetrapygus niger). During this time, we learned how to handle them, how to manufacture delicious algae pellets for them and to set up all the necessary equipment in the laboratory to finally start our main experimental study. We collected red urchins from hatchery tanks at the aquaculture institute and black sea urchins from the bay in front of the university. They moved into their new homes that were cozy 300 ml cups with yellow lids.

We tested the effects of 10 different temperature levels on the urchins and their consumption rates and we realized five of them simultaneously in a static set-up during two experimental trials. Static set-up means that the water, which is inside of our replicate cups, was not exchanged via a flow-through but through manual water exchange. So, our usual working day started with 1.5 hours of water exchange, which we did in the morning by splashing our urchins with 300 ml of fresh Pacific water – that was previously heated up to the target temperature of course. And actually it also ended with a manual water exchange – sometimes late at night, depending on our daily tasks. While the Black Sea Urchins preferred to sit on the bottom of the replicate cups or directly on their food pellets, the ambulacral feet of the red urchins happily danced around in the water column checking out the Ulva pellets. They always amazed us when we watched them and we really fell in love with our little friends! J We measured the change in the urchin’s biomass during the experiment and quantified their consumption of Ulva pellets. Even if Ulva sp. is not the main natural food source for these urchin species, it is rich in nutrients and you find Ulva species all over the world. The reason why we used this alga species is that it allowed the later global comparison of grazer consumption rates, since all GAME teams of this year used manufactured Ulva pellets for their experiments. In the moment, when some urchins at the hottest treatment level (26 °C) began to die, we were really sad. Later (after having got all the data we needed) we celebrated a festivity for them (BBQ on the “container” with a burial of ashed urchins in the sea, haha).

One experimental trial took us 20 days and we did two consecutive trials. So, by the time we finished the second trial it was already mid of July. The manual water exchange, pellet cooking, late night pellet exchange, feces filtering (by using previously cut opened and emptied tea bags) and many other tasks made us really tired. But – no time for long breaks – we directly started to prepare the second experiment.

#2: The Algae & Interaction Experiment

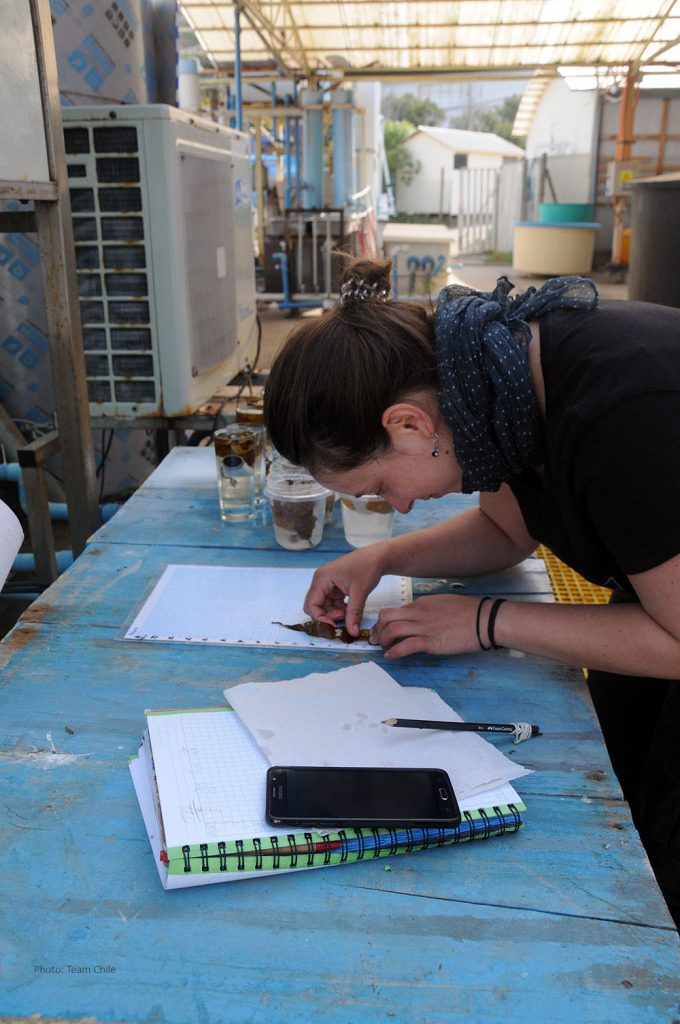

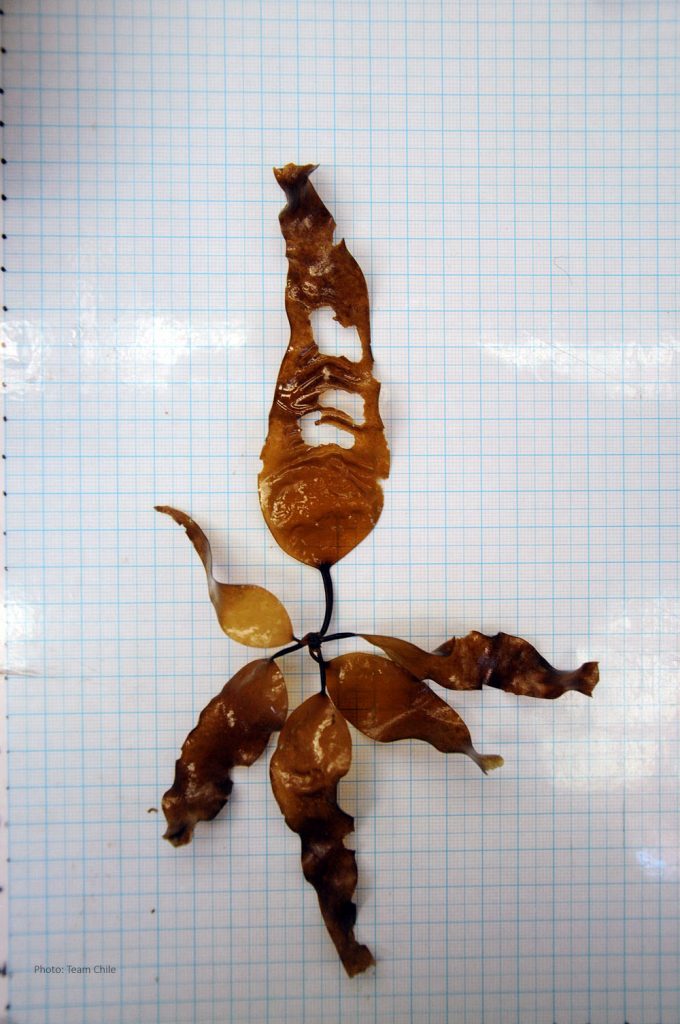

Urchins love kelp. We do too! For our second experiment we initially planned to work with one of the many Lessonia species and/or with Macrocystis sp. However, during field trips we discovered that it will be really hard to find enough same-sized juvenile Lessonia individuals on the rocky shores of the Coquimbo area because they live in the difficult to access splash zone. However, to work with adults of these kelp species, you would need to build enormous tanks, ‘cause Lessonia can reach up to 2 meters in length and Macrocystis even up to 20 m!!!. We were offered a great chance and took the opportunity to work with juvenile Macrocystis pyrifera from an aquaculture farm. In the beginning we stored them in big tanks and planned also to cultivate them for some time in the La Herradura Bay in front of the Campus’ shore. But massive epiphyte growth in the bay made us change our plan, so we cultivated the algae only in the tanks until we were ready and had set everything up to start the experiment.

In contrast to the first, the second experiment took place outside to provide the algae natural light conditions. Three tanks – one tank had the ambient water temperature of the bay and served as an experimental control, while the two further tanks were reserved for treatment levels with elevated temperatures – were running simultaneously. This experiment was (luckily) designed with a flow through-system, which was a big help. By this the algae continuously got fresh, nutrient rich sea water, which was heated up to the respective target temperature while running through a 30 m long pipe that was looping around in the water baths of our temperature treatment tanks.

In the mornings and evenings we “danced our algae” which means we moved them with a little stick and by this created some water movement in the replicate tanks. That was necessary to clean the algae from epiphytes and also to make sure that they are not stuck in a corner of their tank. The second experiment had only 180 replicates, what was a lot less compared to the 225 replicates we used to have in our first experiment, BUT now our replicate tanks contained about 6.5 liters of sea water each instead of only 300 ml… Every few days it was necessary to clean the tanks from biofouling, which meant lifting, cleaning and moving 180 units with 6.5 liters of water each. By the end, when we finished the second experimental trial we had roughly carried 18 720 liters (!!!) of water around and we got pretty strong, haha.

During the two trials, we measured the change in biomass in Macrocystis, its growth rates, its photosynthetic activity via PAM and maybe later in Germany we will analyze frozen tissue samples to determine C:N ratios and phlorotannin concentrations. During two occasions per trial, we also let the algae interact with our grazing friends Loxechinus and Tetrapygus during night time (yeah – we liked to make our lifes as complicated as possible 😉 ). For this, we moved the algae into the 300 ml cups that we used in the first experiment for 6 hours. During this time, one third of the algae replicates were allowed to live happily and grow without any disturbance; another third was sharing the cup with a red or a black sea urchin, but the algae and the urchins were separated by a gauze (so only a chemical interaction between the two could occur and nutrients from the urchin’s feces might have passed), while the last third of the algae was in direct contact with an urchin.

We expected to see either a net loss in biomass or a reduction in growth due to the combination of feeding pressure and heat stress or to see some compensatory growth in the grazed algae.

Chilean way of life

While Martín’s life besides university (if there is a life besides university ;-)) takes mostly place in La Serena, Nora is living in the guest houses (cabañas) of the campus together with other international students. From there you have a beautiful view over La Herradura Bay and the “pampilla” is not far to chill out on a warm rock between cactuses and lizards.

Weekend trip to the marine protected area Reserva National Pingüino de Humboldt at the caleta Punta de Choros, just 2 hours from Coquimbo!

A few weekend trips were possible – if there was no water/pellet exchange, feces filtering, appointments with our supervisor on Saturday mornings, measurements of dry or ash weight – but there is still so much to discover in beautiful Chile! This year an incredible amount of rain has fallen in the Coquimbo region, so you see hills that are very green and flowery instead of only green cactuses in a brown and dry desert.

Flowering Desert/ Dersierto Florido” occur only in very rainy winters (or at least what the Chilenos up North describe as “very rainy” ;)). Here a picture of the pampilla at sunset with beautiful flowers.

After our last experimental day, we celebrated Chile’s Day of Independency on the 18th of September and Martín took some free time to visit his favorite fishing village “Caleta Chañaral”, which is up north, while Nora participated in another fieldtrip with some colleagues. We both put our heads under water and explored the Macrocystis and Lessonia communites. When you see the kelp moving under water through currents and waves, it looks like a wonderful mysterious forest dancing with the tides. It is even prettier than all the dances of our urchins and algae in our replicate tanks! Bakan! One day you should explore it too!

Snorkeling just in front of the university in La Herradura Bay. We found a really big adult red urchin (pretty exciting and very tasty)!

We look forward to meet all the other Gamies back in Kiel, but before we will try to recharge our batteries as much as possible during our last week in the Chilean spring sun next to the sound of the South Pacific.

Saludos y abrazos, Martín & Norita

Amazing fieldtrip my friends ! See you around