——-ENGLISH VERSION BELOW —————————————————————-

Nach zwei Wochen auf See haben wir uns auf dem FS SONNE entgültig häuslich eingerichtet. Alle Wissenschaftler:Innen haben Ihre Routine gefunden, wissen wo welches Labor und die Waschmaschine ist, wann die Kaffeepausen sind (10 Uhr und 15 Uhr, nicht zu spät kommen) und wo sich der Sportraum befindet.

Moin Moin Mola Mola

Auf See treffen wir auf eine Vielzahl an Vögeln und natürlich Meeresbewohnern. Vor einigen Tagen begleitete uns für eine Weile ein kleiner Finnwal, der dem Schiff sehr anhänglich begegnete. Hydroakustische Messungen waren gerade nicht im Stationsplan vorgesehen und alle freuten sich über das neugierige Tier. Eine Besonderheit, die selbst die erfahrenen Marine Mammal Observer überraschte, ist die Präsenz von Mondfischen (lat. Mola-Mola, Sunfish auf Englisch) im Forschungsgebiet. Immer mal wieder treibt träge eine große weißlich schimmernde „Scheibe“ am Schiff vorbei, teilweise mit einem Durchmesser von 2-3 Metern. „Fun fact“ dazu von unserem PAM-Team: Mola Mola scheinen grummelige Laute von sich zu geben, wenn man ihnen zu nahe kommt.

Mola Mola Familie (credits: Bruce MacTavish).

Mola Mola (credits: Bruce MacTavish).

OBS Retrieval – oder: „Wiedersehen macht Freude

Währenddessen hat auf dem Schiff die erste OBS-Rückhol-Phase begonnen. Ein uraltes Sprichwort in der Seismik besagt: „Es ist leicht, ein OBS über Bord zu werfen, es wiederzufinden jedoch, ist eine große Kunst.“ Keine Sorge, dass ein OBS tatsächlich verloren geht, passiert äußerst selten und das Team von SO294 hat bisher erfolgreich alle Geräte wieder geborgen. Für alle Fälle ist allerdings auf jedem OBS die Kontaktdaten der Besitzer:Innen (das Forschungsinstitut), sowie ein Versprechen auf Finderlohn bei Rückgabe angebracht.

Wenn die OBS also früher (Kurzzeit) oder später (Langzeit) wieder auftauchen, beginnt die Schatzsuche. Die Koordinaten an der die Geräte zu Wasser gelassen wurde sind bekannt, das Schiff steuert also die Koordinaten an und wir geben das Signal zum Lösen vom Anker. Bei Wassertief von über 2000m ist die Auftauch-Position nicht auf den Meter genau bekannt und wir suchen das OBS auf die letzte Distanz auf Sicht. Hilfreich dabei sind Peilsender, ein installierter Blinker und eine leuchtend orangene Fahne.

“Be there or be square” für dieses OBS trifft glücklicherweise beides zu und die Daten können ausgelesen werden (Credits: Sarah-Marie Kröger).

Coring – because geologists love digging up the past

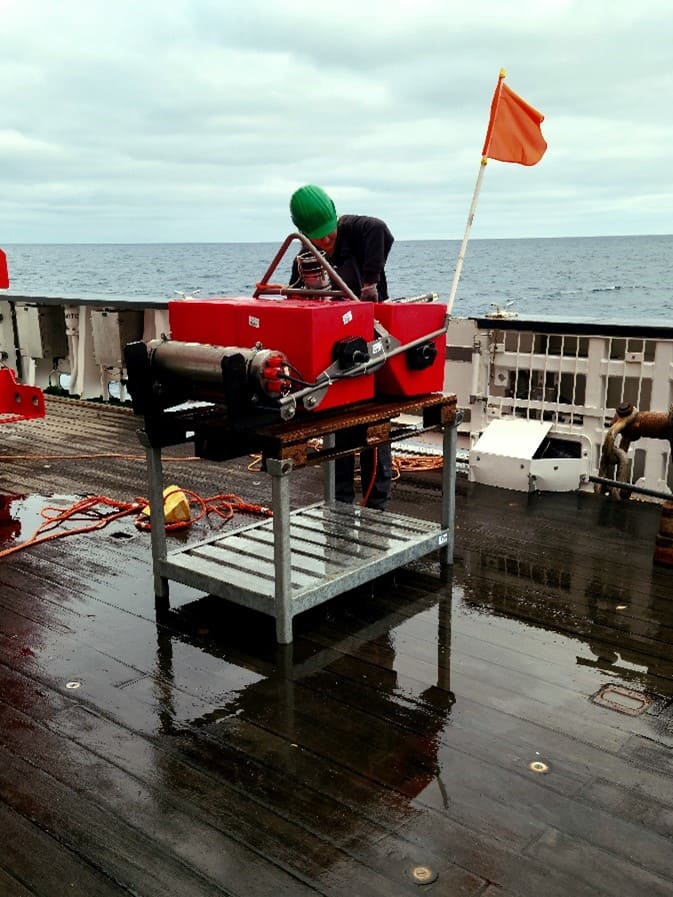

Ein weitere Methode, welche in der Meeresforschung nicht fehlen darf, ist die Beprobung der Sedimente am Meeresboden. Es gibt dafür verschiedene Gerätetypen, je nach Forschungsfrage und Einsatzgebiet. Für diese Reise haben wir das Schwerelot im Gepäck.

In der Theorie ist das Prinzip denkbar einfach: das fünf Meter lange Schwerelot wird ins Wasser gelassen und dank eines tonnenschweren Gewichts „stanzt“ er aus dem Meeresboden Sediment aus, wie ein Keksförmchen den Teig. Das Lot wird wieder an Deck geholt; innen befindet sich ein Rohr aus PVC, indem sich der Kern befindet. Ein „Kernfänger“ am Boden des Lots sorgt dafür, dass das Sediment auf dem Weg an die Meeresoberfläche nicht wieder herausgleitet. Das PVC-Rohr wird dann noch auf dem Schiff zerlegt, je nach Forschungsvorhaben auch beprobt und anschließend werden die Kernfragmente bis zum Ende der Reise verstaut. Nicht ganz so einfach ist die tatsächliche Umsetzung – Es müssen eine Vielzahl von Parametern beachtet werden und selbst dann hat man nicht immer Erfolg und das Gerät kommt leer wieder an die Oberfläche.

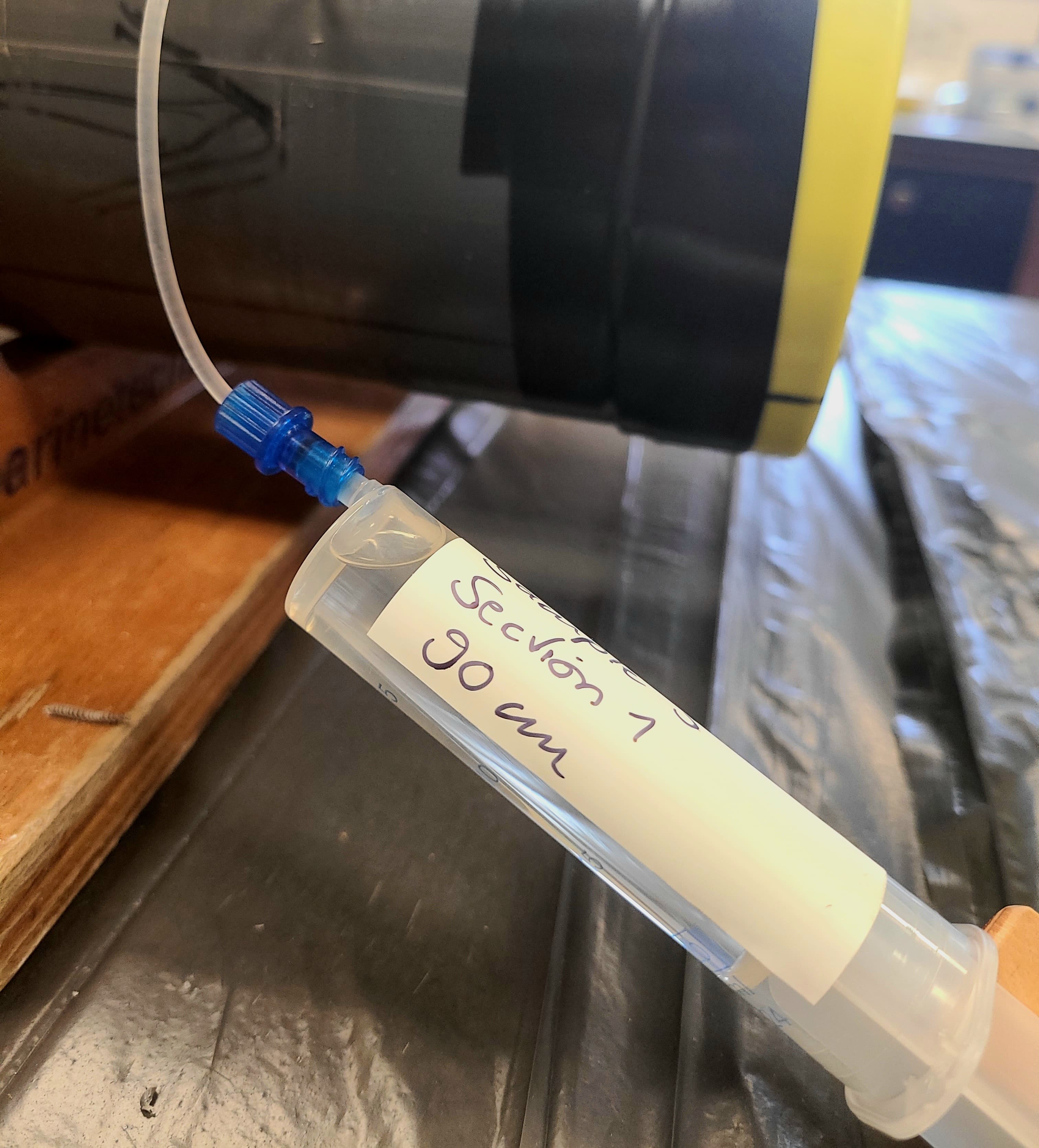

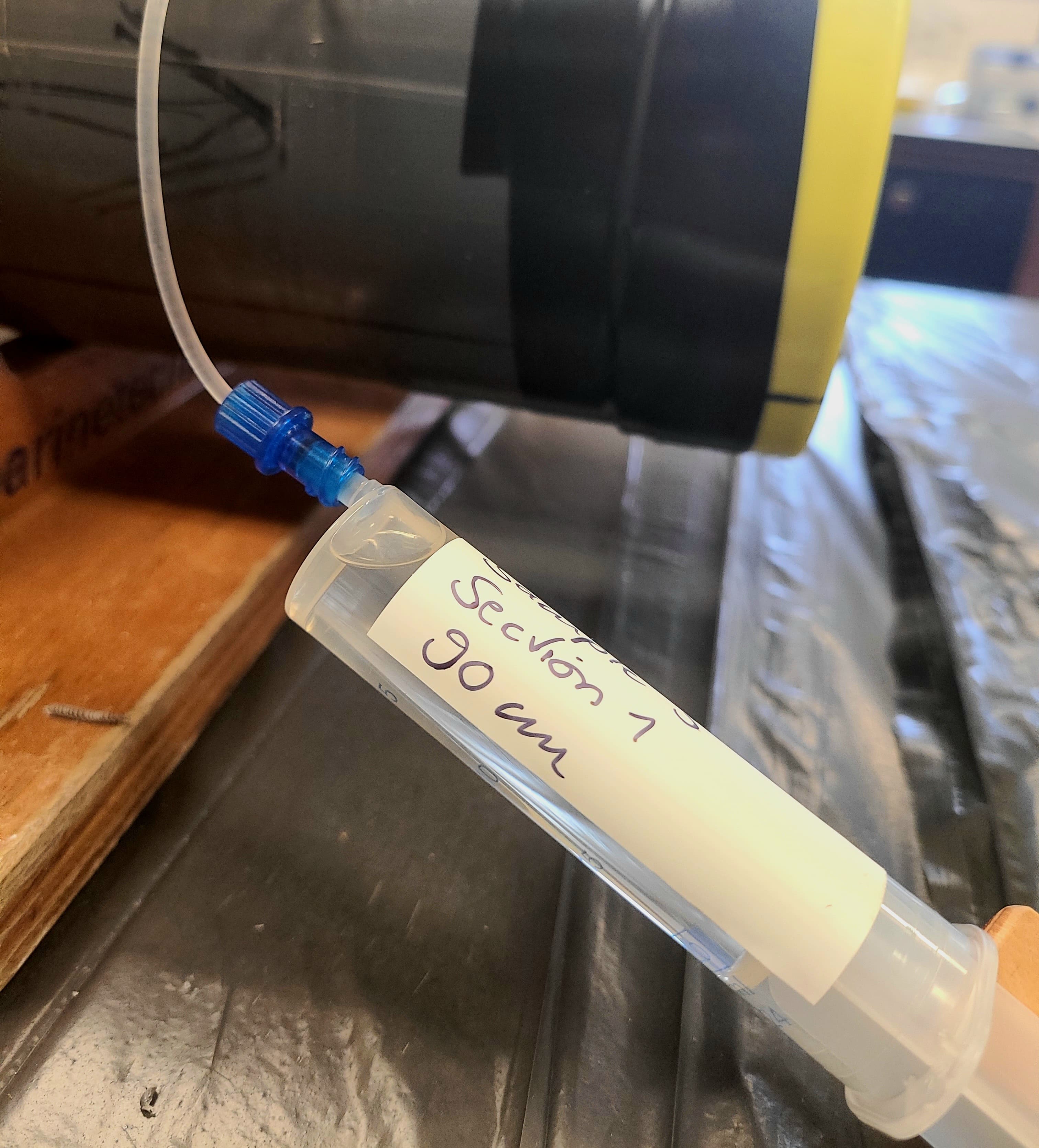

Die Beprobung erfolgt teilweise bereits direkt an Bord in den Laboren

Das volle Schwerelot wird wieder an Deck geholt.

Während wir bisher von wunderbar sonnigem Wetter und idealen Forschungsbedingungen verwöhnt wurden, ist der erste Kern-Tag von Seegang und Wind und Nieselregen gekennzeichnet – das lässt uns auch daran erinnern, dass nicht nur zuhause, sondern auch hier auf See vor Vancouver Island der Herbst begonnen hat.

Das von uns geborgene Sediment hier vor der Küste, ist schmierig zäh, grün-bräunlich und irgendwie – unspannend wie die Nicht-Geolog:Innen an Bord etwas desillusioniert bemerken. Man darf sich aber von der tristen Erscheinungsform des Ozeanbodens nicht täuschen lassen – denn der tonige Boden hat allerlei Geschichten zu erzählen, wenn man ihn denn zu lesen vermag. Im Grunde zeigt ein ungestörter Kern wie ein Archiv die geologische Vergangenheit der Region. Mithilfe von Mikrofossilien und der Radiokarbon-Datierung lässt sich das Alter in jedem Sedimentabschnitt bestimmen, Geochemiker:Innen beproben das Porenwasser unter anderem auf Spurenelemente und Umweltwissenschaftler:Innen suchen im Sediment nach Mikroplastik.

Und Seismolog:Innen? Hier an Bord untersuchen wir, ergänzend zu den seismischen Daten, die Kerne auf Spuren vergangener Events. Unterseeische Hangrutschungen werden gerade in seismisch aktiven Regionen häufig von Erdbeben ausgelöst. Ist im Kern also ein Event zu finden, welches auf eine solche Hangrutschung hinweist, könnte das Auskunft über ein vergangenes Beben liefern.

PART 2 ——ENGLISH VERSION————————————————

After 2 weeks at sea, everyone on the RV SONNE has finally settled in. All scientists have found their routine, know where the lab and the washing machine are, coffee break times (10am and 3pm, don’t be late) and where the fitness room is located.

Moin Moin Mola-Mola

At sea we encounter a variety of birds and of course sea creatures. A few days ago, we were accompanied for a while by a small fin whale, which was very affectionate to the ship. Hydroacoustic measurements were not in the station plan and everybody was happy about the curious animal. A special feature that surprised even the experienced marine mammal observers is the presence of many sunfish (lat. Mola-Mola, Moonfish in German) in the research area. Every now and then a large white-ish shimmering “disc” drifts lazily past the ship, sometimes with a diameter of 2-3 meters. “Fun fact” from our PAM-team: Mola-Mola seem to make grumpy sounds when you get too close to them.

A family of Mola Mola passing by (credits: Bruce MacTavish)

Mola Mola (credits: Bruce MacTavish)

OBS – We just love reunions!

Meanwhile, on the ship, the first OBS retrieval phase has begun. An ancient wisdom in seismology says, “It’s easy to throw an OBS overboard, but finding it again is a big job.” Don’t worry, losing an OBS happens rarely and the SO294 team has successfully recovered all devices to date. Just in case, however, each OBS has a label attached with the contact information of the owner (the research institute), as well as a promise of refund if returned.

Be there or be square – luckily this is correct in both ways for this OBS – the data can be collected (credits: Sarah-Marie Kröger).

When the OBS turns up sooner (short term) or later (long term), the treasure hunt has begun. The coordinates where the equipment was deployed are known and the ship heads for the coordinates, where we give the signal to release the OBS from its anchor. At water depth above 2000 m the position where the OBS may surface again is not 100% known, and we search for the OBS on sight. Extremely helpful: direction finders, an installed flasher and a bright orange flag.

Coring – because geologists love digging up the past

Another piece of equipment that is indispensable in marine research is the corer. There are different models, depending on the research question and the field of application. For this cruise we brought the gravity corer.

In theory, the principle is easy: the five-meter-long gravity corer is lowered on a wire into the water and, thanks to a top- weight of 1 ton, it “punches out” sediment from the seafloor like a cookie cutter punches out dough. The corer is brought back on deck; inside there is a tube made of PVC which holds the sediment core. A core catcher at the bottom of the tube ensures that the sediment does not slide out on its way to the surface. The PVC tube is disassembled on the ship and, depending on the research project, sampled. After that, the core fragments are stowed away until the end of the voyage. The actual procedure is not that simple – many parameters have to be considered and scientists are not always successful – the device comes back to the surface without sediment.

THE PVC – tube containing valuable material is segmented.

The core is hieved back on board.

5 m long Gravity Corer.

While we have been spoiled by wonderfully sunny weather and ideal research conditions so far, the first core day has been characterized by swell and wind and drizzle – this also reminds us that autumn has begun not only at home, but also here at sea off Vancouver Island.

The sediment we recover off the coast, is sticky, green-brownish and somehow – unexciting as the non-geologists on board remark somewhat disappointed. But don’t be deceived by the dreary appearance of the ocean floor – because the clay has all kinds of stories to tell if you are able to read it. An undisturbed core reveals the geological past of the region like an archive. With the help of microfossils and radiocarbon dating, the age of sediment can be determined, geochemists sample the pore water for trace elements among other things, and environmental scientists search for microplastics.

The corer is deployed.

The sediment can be processed directly on board in the labs.

And seismologists? In addition to the seismic data, we investigate the cores for past sediment failure events. These submarine landslides are often triggered by earthquakes, especially in seismically active regions as this one we work in. If an event is found in the core that indicates such a landslide, this can provide information about a past earthquake.