by Benson Mbani

Two weeks into my summer holiday, while dancing along to the Jerusalema dance challenge, an email came through which needed urgent action. Usually while on holiday, I only briefly check emails every few days, and only respond to urgent ones. It was from Dr. Timm Schoening – my supervisor and chief scientist for this cruise. But why would he send me an email that needed my action when he knew I was on vacation?

“… would you like to join our cruise ‘Metal-ML’ across the Atlantic Ocean in October? …” read the email in part. Why wouldn’t I want to join any cruise to any part of the world? Especially one that I don’t have to pay for? I wondered to myself. “Of course, I would like to join” I responded as I partly danced along to Jerusalema dance. You see there is that part of the dance where you have to play your feet in some funny type of way as you make the turn. Took me a couple of tries to get it right ;). Anyway, when the day finally came, we drove about 5 hours from Kiel to Emden, which is the departure port where the ship was docked waiting for us to give it company as it cruises into the rough waters of the Atlantic. As is required, we had to follow laid down standard health guidelines. After the mandatory strict pre-cruise quarantine period, and with a negative COVID test result in hand, it was finally time to board Germany’s second most modern ocean research vessel named after Maria S. Merian. A magnificent piece of engineering.

But what research do I even do at GEOMAR? Broadly speaking, my thesis is about underwater computer vision, which involves machine learning, applied statistical pattern recognition and image processing techniques to challenges related to seafloor image understanding. But why do we even need image understanding anyway? What does it even mean? Can’t we just stare at the images and see what is in them?

As it turns out, image analysis is a relatively easy and trivial task for a human above the age of five to tackle. What is not so obvious, however, is how the human brain is an advanced ‘supercomputer’ that integrates the visual sensory information that comes in through the eyes with other information such as prior experience, that makes it effortless for us to understand and interpret image content, in some cases even for images we have never seen before. The problem is that humans suffer fatigue and bias really quickly, and so despite the fact that we are good at image interpretation, it is neither feasible nor scalable to rely on human interpreters to analyze the terabytes worth of image and video that is generated during deep-sea expeditions.

The obvious alternative is to train computers to mimic the human visual system and automatically do image understanding for us. Believe it or not, there is no obvious way to train computers to be as competent as humans in image understanding. Partly because the human visual system is not fully understood, thus not easy to conceptualize and program as an algorithm. In addition, the fact that computers view an image as a set of ‘numbers’ on a grid represented as a matrix also makes this task relatively non-trivial. Consequently, training computers to be able to transform these ‘raw numbers’ into useful information is at the core of computer vision research. Being able to train computers to achieve such a task allows marine researchers to non-invasively sample large benthic habitats using underwater cameras and rely on the computer vision algorithms to do the image interpretation tasks automatically as they focus on the science.

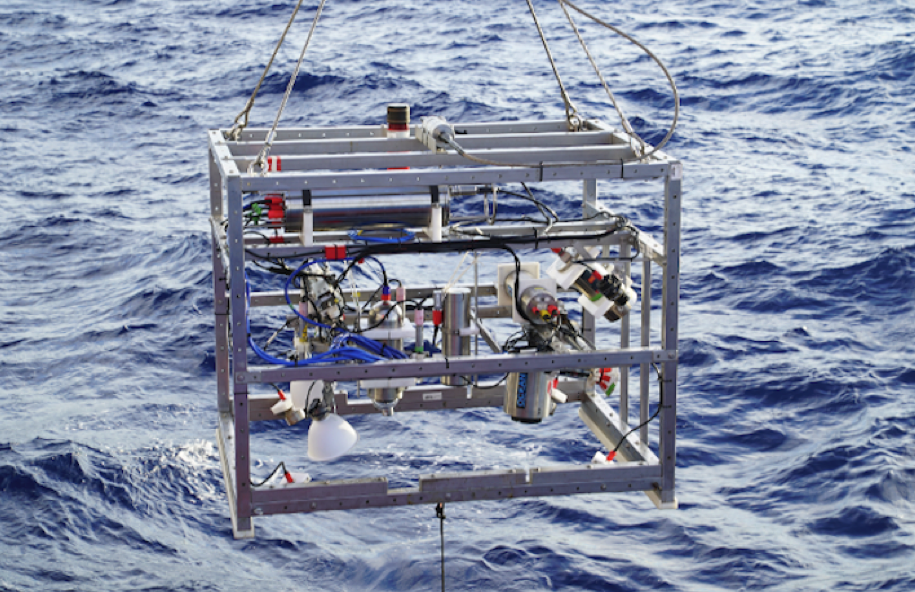

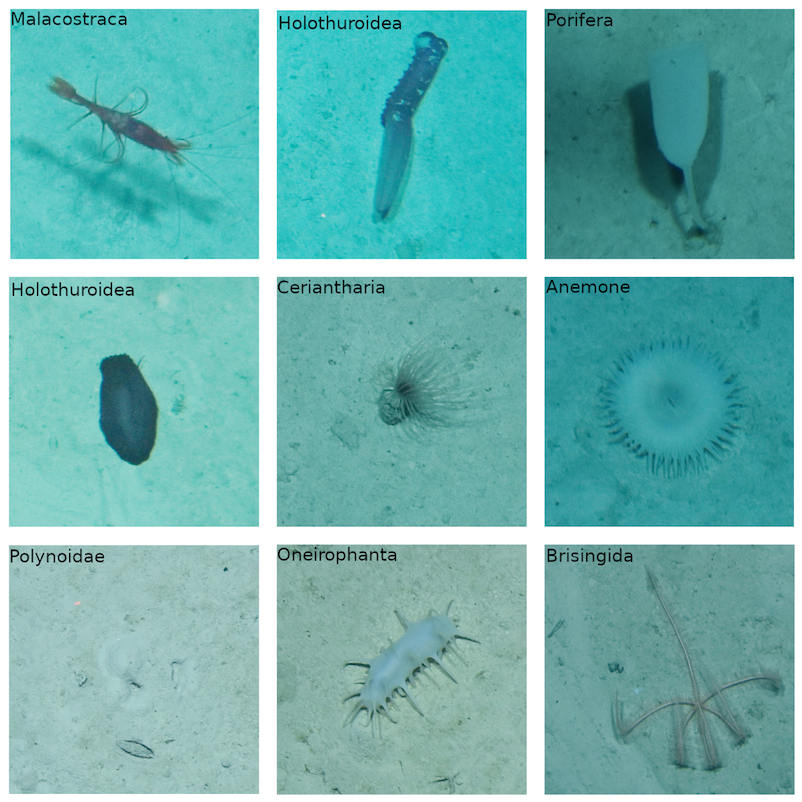

Back to the cruise! As would be expected, I was part of the team of scientists dealing with the Ocean Floor Observation System (OFOS). Figure 2 shows the OFOS we used during the MSM96 cruise. The OFOS shown below is a system comprising video and still photo cameras used to survey the deep sea floor. It is connected to the vessel by a 7 km fiber optic cable that maintains a continuous direct connection which we rely on for live seafloor video streaming at a resolution of 4K. Also, the OFOS is equipped with a photo camera which captures high resolution still photos every second. Figure 3, below, shows a sample of still photos captured and annotated during the MSM96 cruise on board Maria S Merian.

So, what goes on in a typical day at sea? First, we prepare a transect along which we need to collect video and photos. This information is then sent to the crew at the bridge who then steer the ship to the start of the transect and position it so as to be stationary, ready for OFOS deployment. The OFOS is then gradually lowered 5 kilometers into the water column. It takes roughly 2 hours to arrive at the seafloor. Once close to the seafloor, we optimize the camera settings remotely to get clear pictures with good contrast. The live stream from the OFOS is relayed to a big screen in the lab from where we begin annotating benthic fauna as the ship is moving along the transect. Since it takes at least 12 hours to complete imaging a transect, we work in shifts through the night.

After we have sampled the entire transect, we store and back-up the data onto our NAS devices and immediately start preliminary on-board image analysis on the newly acquired image sequences and recorded videos. For each image frame (on both the still photos and videos), we extract features – which means properties/characteristics of the image. For instance, for each image we automatically extract the mean color and entropy as proxies for entire image sequences. We also do laser point detection to calculate the area of seafloor imaged in square meters.

It’s been almost 5 weeks since we left Kiel to start the cruise, that means it’s been more than six weeks since I did the Jerusalema dance, which is not a good thing, obviously. The thing with cruising in the Atlantic is that it can get so rough sometime. That means it may not be a good idea to do the dance on board. But Maria S Merian is a beautiful vessel and so there were always plenty of options to safely keep fit in the sport room, after the image analysis work for the day is done, of course 😊