— Deutscher Text folgt unten —

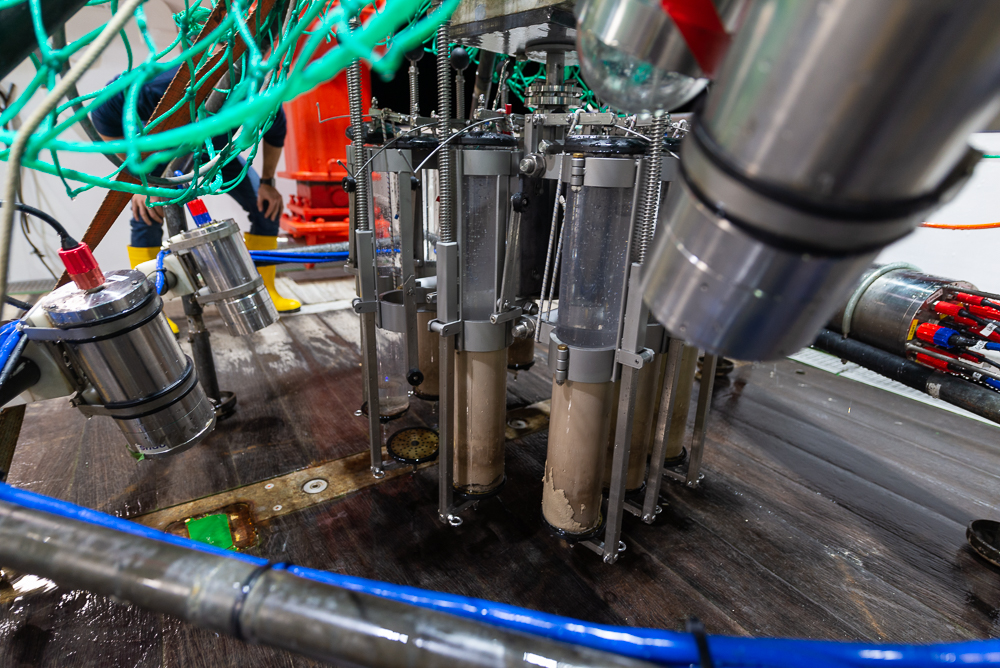

The geochemistry group leader runs into the mess, shouting “SURPRISE MUC IN 15 MINUTES!”. Our adrenaline levels shoot through the roof. Everyone leaves their coffee/tea behind, we walk rather quickly (no running on deck!), clothes get changed, everyone is on their post. After three weeks on the research vessel, we now know the drill. The Multi Corer (MUC) is always ready to be deployed. Together with the crew of RV Maria S. Merian, the MUC is gently heaved over the side of the vessel and begins its long and dark descent into the depth of the ocean. Now we wait…After around two hours it reaches the seafloor at roughly 5400 m water depth and only thanks to the support of our skilled and seasoned technicians, we are able to place the MUC at the ocean floor at just the right speed. Our only information is the change of the rope tension. As we give the signal to heave the MUC back up to the surface, all eyes are fixed on the computer screens trying to decipher whether all liners closed correctly making our operation successful or not. Now the first bets are made. How many of the twelve liners are filled? Some hope for all. Some secretly hope for less so they can catch up on the lost sleep. Again, now we wait and prepare our instruments and sampling material. Last minute caffeine doses are taken in and as the MUC is safely lashed back on the working deck, the geochemistry group swarms out like a team of formula 1 mechanics (humble brag). Everyone knows their task in their sleep now.

(Photo by Nico Fröhberg)

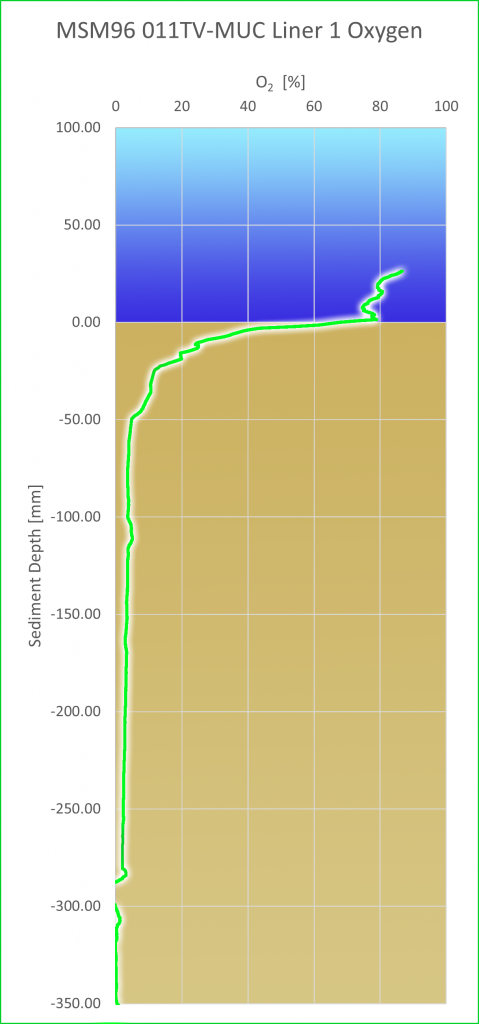

Once all the liners (yeah twelve!) are taken out of the Multi Corer they are photographed and transported into the scientific cool room of the ship, where we have set up one of our many lab spaces to process the sediment cores at the same temperature they had on the seafloor. Our most pressing question now: Is the sediment oxic or not. If all the oxygen has been consumed within the sediment cores we investigate, we mustn’t expose it to the oxygen in the air but have to process the samples in a glove bag under nitrogen atmosphere. With great hurry (and care!) the first core is placed in a rather oversized device to measure the oxygen concentration. An electrode is attached to a profiler that moves it vertically to determine high resolution oxygen concentrations within the sediment core. Depending on how fast the oxygen concentration changes over depth, high resolution measurements with increments as small as 0.1 mm can be conducted by Willi the profiler, named so for the whale-like noises it makes occasionally.

(Photo by Nico Fröhberg)

After the first oxygen measurement is completed, sampling of the other cores begins. After further processing in the cool room, the sediment samples are transported to the upstairs laboratory. There, the pore water is extracted and sampled for various parameters and immediate on-board nitrate measurements.

(Photo by Nico Fröhberg)

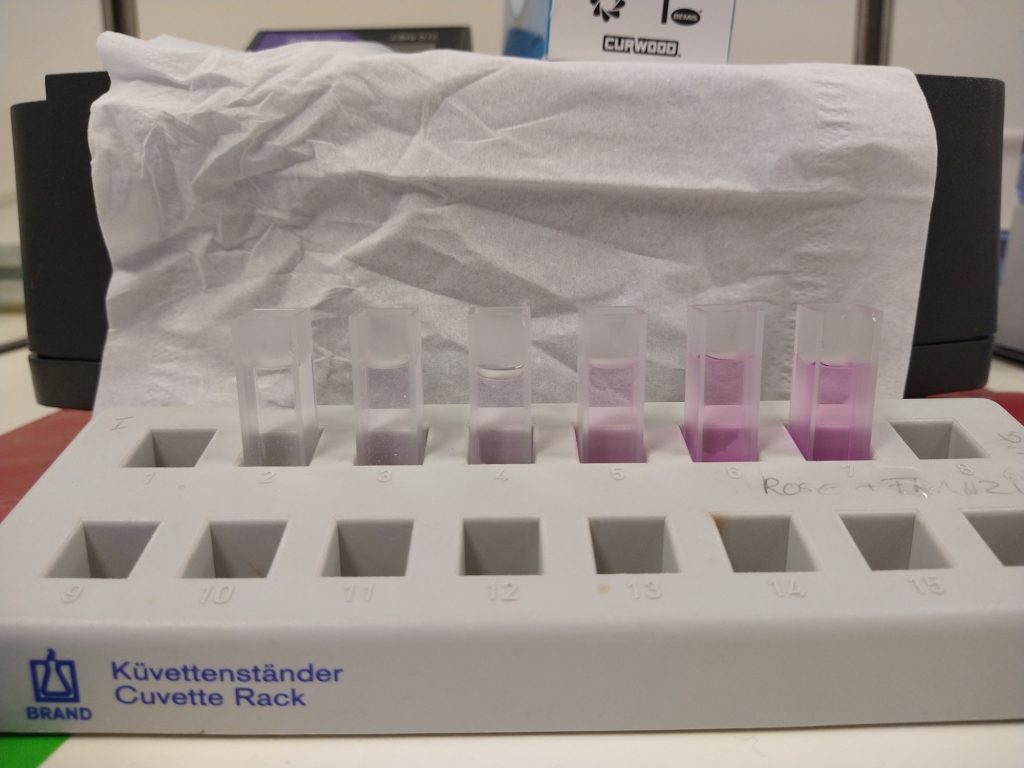

Nitrate acts as one of the most important nutrients for life in the ocean and is often a limiting factor for growth of marine organisms. After oxygen, it yields the second highest amount of energy for the oxidation of organic carbon by microbial life. Nitrate is released within the sediment by remineralization of the remains of marine organisms. Together with the oxygen concentration, the nitrate concentration gives us information about the redox state of the pore water. Therefore, its concentration is measured photometrically at 1-4 cm resolution at each sampling location. To determine the nitrate concentration, two chemical reagents are added to the sample to firstly reduce the present nitrate to nitrite, which then forms a pinkish complex. Finally, the light absorption at a specific wavelength for that colored complex is measured with a photometer. We can then calculate the nitrate concentration in the sample according to the calibration curve, which was obtained by repeated measurement of reference material.

(Photo by Nico Fröhberg)

Three weeks, 26 Multi Corer deployments, 37 oxygen profiles with a total of 5848 measurements and roughly 400 nitrate measurements later, we have almost completed the sediment sampling program. In the next couple of days, we are on our way back to the PAP (porcupine abyssal plain) research area where we want to finish up our work.

We are excited and looking forward to dust off the mud and begin working on our samples in the home laboratory.

Cheers from board of RV Maria S. Merian!

Überraschungs-MUC!

Die Leiterin der Geochemie-Gruppe rennt in die Messe und ruft: “ÜBERRASCHUNGS MUC IN 15 MINUTEN! Unser Adrenalinspiegel schießt durch die Decke. Alle lassen ihren Kaffee/Tee zurück, Stühle fallen um. Wir rennen (bzw. gehen schnell) an Deck, die Kleidung wird gewechselt, jeder ist auf seinem Posten. Nach drei Wochen auf dem Forschungsschiff wissen wir jetzt, wie es läuft. Der Multi Corer (MUC) ist immer einsatzbereit. Zusammen mit der Besatzung des FS Maria S. Merian wird der MUC sanft über die Bordwand gehievt und beginnt seinen langen und dunklen Abstieg in die Tiefe des Ozeans. Nun warten wir… Nach etwa zwei Stunden erreicht er den Meeresboden in etwa 5400 Meter Wassertiefe und nur dank der Unterstützung unserer erfahrenen Techniker sind wir in der Lage, den MUC mit genau der richtigen Geschwindigkeit am Meeresboden zu platzieren. Unsere einzige Information ist die Änderung der Seilspannung. Während wir das Signal geben, den MUC wieder an die Oberfläche zu hieven, sind alle Augen auf die Computerbildschirme gerichtet und versuchen zu entziffern, ob alle Liner korrekt geschlossen sind, was unsere Operation erfolgreich macht oder nicht. Jetzt werden die ersten Wetten abgeschlossen, wie viele der zwölf Liner gefüllt sind. Einige hoffen auf alle. Einige hoffen insgeheim auf weniger, damit sie den verlorenen Schlaf nachholen können. Auch jetzt warten wir wieder und bereiten unsere Instrumente und unser Probenmaterial vor. In den letzten Minuten werden koffeinhaltige Getränke eingenommen, und als der MUC wieder sicher auf dem Arbeitsdeck festgezurrt ist, schwärmt die Geochemie-Gruppe aus wie ein Team von Formel-1-Mechanikern. Jeder kennt seine Aufgabe jetzt im Schlaf. Sobald alle Liner (ja zwölf!) aus dem Multi Corer genommen sind, werden sie fotografiert und in den wissenschaftlichen Kühlraum des Schiffes transportiert, wo wir einen unserer vielen Laborräume einrichten haben, um die Sedimentkerne bei der gleichen Temperatur zu verarbeiten, die sie auf dem Meeresboden hatten. Unsere dringendste Frage jetzt: Ist das Sediment oxisch oder nicht.

Wenn der Sauerstoff innerhalb der von uns untersuchten Sedimentkerne verbraucht wurde, dürfen wir sie nicht dem Sauerstoff in der Luft aussetzen, sondern müssen die Proben in einer Glovebag unter Stickstoffatmosphäre verarbeiten werden. Mit großer Eile (und Vorsicht!) wird der erste Kern in ein ziemlich überdimensioniertes Gerät zur Messung der Sauerstoffkonzentration gestellt. Eine Elektrode wird an einem Profiler befestigt, der sie vertikal im Kern bewegt, um hochauflösende Sauerstoffkonzentrationen innerhalb des Sedimentkerns zu bestimmen. Je nachdem, wie schnell sich die Sauerstoffkonzentration mit der Tiefe ändert, können hochauflösende Messungen mit Inkrementen von nur 0,1 mm durchgeführt werden, von Willi, dem Profiler, so benannt wegen seiner walähnlichen Geräuschen, die er gelegentlich von sich gibt. Nachdem die erste Sauerstoffmessung abgeschlossen ist, beginnt die Probenahme der anderen Kerne. Nach der Weiterverarbeitung im Kühlraum werden die Sedimentproben in das Labor im Obergeschoss transportiert. Dort wird das Porenwasser aus dem Sediment extrahiert und für verschiedene Parameter und sofortige Nitratmessungen an Bord beprobt. Nitrat wirkt als einer der wichtigsten Nährstoffe für das Leben im Ozean und ist oft ein limitierender Faktor für das Wachstum von Meeresorganismen. Nach Sauerstoff liefert es die zweithöchste Energiemenge für die Oxidation von organischem Kohlenstoff durch mikrobielles Leben. Nitrat wird innerhalb des Sediments durch Remineralisierung der Überreste von Meeresorganismen freigesetzt. Zusammen mit der Sauerstoffkonzentration gibt uns die Nitratkonzentration Auskunft über den Redoxzustand des Porenwassers. Daher wird seine Konzentration an jeder Probenahmestelle photometrisch mit einer Auflösung von 1-4 cm gemessen. Um die Nitratkonzentration zu bestimmen, werden der Probe zwei chemische Reagenzien zugesetzt, um zunächst das vorhandene Nitrat zu Nitrit zu reduzieren, das dann einen rosafarbenen Komplex bildet. Schließlich wird die Lichtabsorption bei einer bestimmten Wellenlänge für diesen farbigen Komplex mit einem Photometer gemessen. Somit können wir die Nitratkonzentration in der Probe anhand einer Kalibrationskurve berechnen, die durch wiederholte Messung von Referenzmaterial erhalten wurde.

Drei Wochen, 26 Multi-Corer-Einsätze, 37 Sauerstoffprofile mit insgesamt 5848 Messungen und etwa 400 Nitratmessungen später haben wir das Sedimentprobenahmeprogramm fast abgeschlossen. In den nächsten Tagen sind wir auf dem Weg zurück zum PAP-Forschungsgebiet (Porcupine Abyssal Plain), wo wir unsere Arbeiten abschließen wollen.

Wir sind gespannt und freuen uns darauf, den Schlamm abzustauben und im heimischen Labor an unseren Proben zu arbeiten.

Grüße von den Fahrtteilnehmern der FS Maria S. Merian!