Bottlenecks

In our final blog we will re-capture our journey through the Mediterranean as it is not very often that one gets to travel from one end almost to the other. The Mediterranean is unique because of its numerous passages and straits. These maritime bottlenecks also characterized our journey, but luckily mproved to be the only bottlenecks we had to break! So come along with us and take our tour again through Mare Nostrum, our sea, and learn about its rich cultural and geological inheritance while we are heading towards the port of Heraklion on our last transit, enjoying every glimpse of the sea that we get while packing our equipment, cleaning the labs and getting hooked on the data that we collected over the last weeks – just like scientists do!

See you all back home in a little while,

Heidrun Kopp

Chief Scientist MSM-71, at sea

P.S. The narrow marine straits were the only bottlenecks we had to break during MSM71 – so a big THANK YOU to Sebastian M., Mario B. and Iris S. in the galley for three weeks of culinary treats and of course to Benjamin R. and his troops from the machine, who kept everything running.

Marine straits and their place in geological history

by Anouk Beniest, UPMC The Maria S Merian left Las Palmas de Gran Canaria on the 7th of February 2018 at 4 in the afternoon. Our final destination is the harbour of Heraklion on the island of Crete. In 22 days at sea we have to recover 29 broadband Ocean Bottome Seismometers (OBS). In addition, we will deploy another 48 OBSes and Ocean Bottom Hydrophones (OBH) along two different profiles. To do so, we need to cross the Atlantic and reach the Ligurian Sea through the strait of Gibraltar. Then, after recovery of all stations, we sail through the Strait of Bonifacius in between the islands of Corsica and Sardinia. Next we’ll pass the Ionian Sea through the Strait of Messina. To reach Heraklion, the last strait to take would be the Strait of Kythira – Antikythera. Where do these narrow seaways come from? And what role did they play in recent geological history?

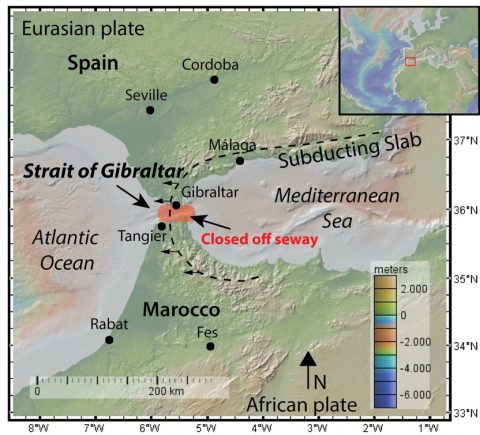

Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar separates the African and Eurasian plates by a 14.3 km stretch of water. Before Africa and Europe became located so closely together, the Tethys Sea separated the two continents. When subduction of the Tethys Ocean was initiated some 90 Ma the Strait of Gibraltar resulted from the northward moving African plate. The narrow

seawa has played a major role during the late Miocene, when around 5.9 Ma when it caused a separation between the Mediterranean waters and the Atlantic Ocean. As a result, limited amounts of less salty and fresh waters entered the Mediterranean basin and it dried out, leaving a massive package of salt at the bottom of the basin. This crisis is now known as the Messinian Salinity Crisis. Only 600.000 years after the closure of the basin, around 5.3 Ma, the barrier at Gibraltar was breached and the so-called ‘Zanclean flood’ filled the basin with water. Over the last 5 myr, sediments have been deposited, covering the salt layers and the Mediterranean Sea as we know it nowadays is the result.

Map of the Strait of Gibraltar, showing the retreating slab and the region that was closed off during the Messinian salinity crisis in 5.33 Ma. Map: Anouk Beniest/UPMC

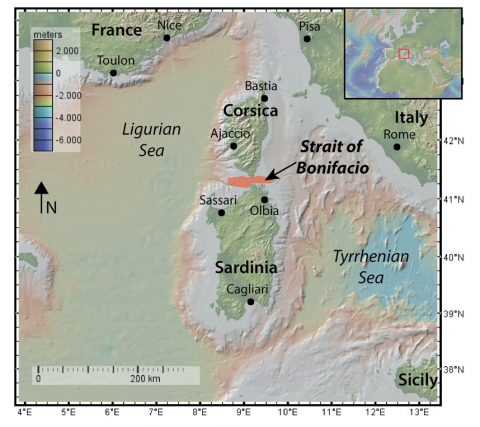

Strait of Bonifacio

The islands of Corsica and Sardinia are separated by the 11 km wide Strait of Bonifacio. Both islands are made of granite and limestone and throughout a large part of their existence they behaved as one big crustal block. To the west and east of the islands the crust is under extension resulting in the Ligurian Sea and the Tyrrhenian Sea. The strait itself is rather shallow, not more than 100 meters deep. It is part of a deep ravine that would surface in prehistoric times when sea level was low. Then the passage would form a land bridge between the two islands.

Map of the Strait of Bonifacio, showing the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian seas that are connected through the Strait of Bonifacio. Map: Anouk Beniest/UPMC

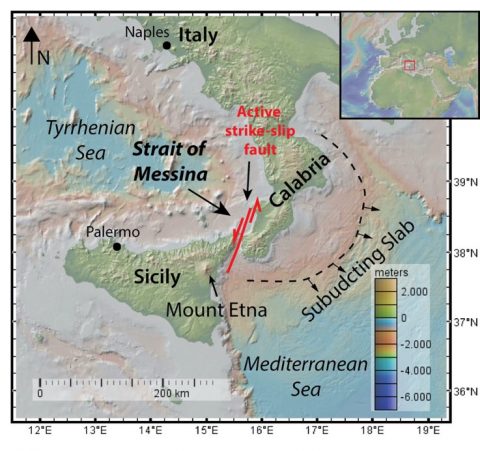

Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina is only 3.1 km wide and separates the island of Sicily from mainland Italy. Currents are strong and in the old days the passage was feared by seafarers. But not only the currents make it a dangerous region. This strait is also one of the most seismic active regions in the Mediterranean realm. In 1908 an earthquake of 7.1 produced a 10 meter high tsunami-like wave and caused 60.000 casualties. Through the seaway a strike-slip fault runs NE-SW. Activity over the last 2.5 million years along this fault has been detected by marine terraces that are now above sea level on the island of Sicily. One of the reasons for the tectonic activity in the region is the retreating, subducting slab below Calabria, mainland Italy.

Map of the Strait of Messina showing the retreating subducting slab southwest of Calabria and the active strike-slip fault that runs through the Strait of Messina. Map: Anouk Beniest/UPMC

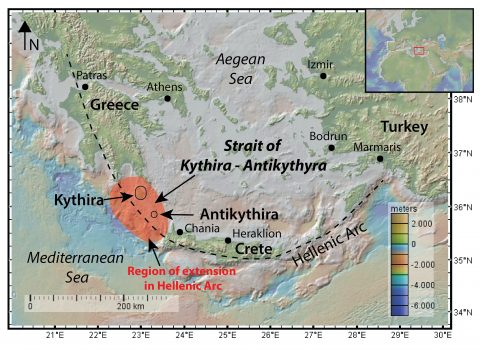

Strait of Kythira – Antikythera

The Strait of Kythira – Antikythera is the widest seaway we will pass through on this mission. It measures roughly 100 km in width and the islands of Kythira and Antikythera are lying in the strait. South of Greece, the Mediterranean Sea is over 4000 meters deep. The passage is much shallower, only 150 meters deep or at some points even less. This is because the Strait of Kythira – Antikthera is a submerged part of the Hellenic Arc, which runs from south-west Greece, through Crete until western Turkey. Compared to the rest of the western Hellenic Arc, the submerged part is being extended faster than the onland parts over the last couple of million years. For that reason, the crust is thinner and submerged, creating a seaway from the Aegean Sea into the deeper Mediterranean Sea.

Map of the Strait of Kythira – Antikythyra showing the Hellenic Arc and the region of relative more extension and thinning that was eventually submerged and provided the seaway between mainland Greece and the island of Crete. Map: Anouk Beniest/UPMC