The past blog entries have shown you the breath-taking and beautiful works of the JellyWeb expedition: we have seen colourful critters, cutting edge technology and brave physicists alone amongst biologists. Our projects on MSM126 are quite diverse and besides all of them being quite exciting, they share one more trait: they all produce a ton of data. Data, that needs to be managed and curated.

I am going to be honest: if I would visit a blog about a deep-sea biology expedition containing posts about the coolest organisms and equipment ever, I would probably skip the part about data management. And I guess this is one of the reasons why jobs like mine exist – scientists love generating data, but managing their own data? That’s a different tale.

If a scientific cruise was a pirate’s adventure, the data we gathered would be the treasure. And everyone here on board works hard to make the treasure-hunt successful. And just like you would find different kind of riches such as diamonds, gold or rare spices, the data we collect is just as diverse. For example, food web ecologists such as Jamileh, Sonia and Florian (see blog post from 21.02.2024) gather thousands of individual organisms with various net types from different depths and areas. Every individual organism undergoes a specific processing, is photographed multiple times, might have been used in multiple experiments and is sub-divided into even more sub-samples for museum collections, food web, genetic and other analyses by the end. So, it is not just one data point but a multitude of physical measurements, organic samples and metadata. And as good scientific practice demands, one should take track and care of these information in order to avoid confusing and incorrect data capture or worst case: data loss. To get a structure into the menacing chaos, scientists usually use standardized protocols which queries all necessary information on the spot.

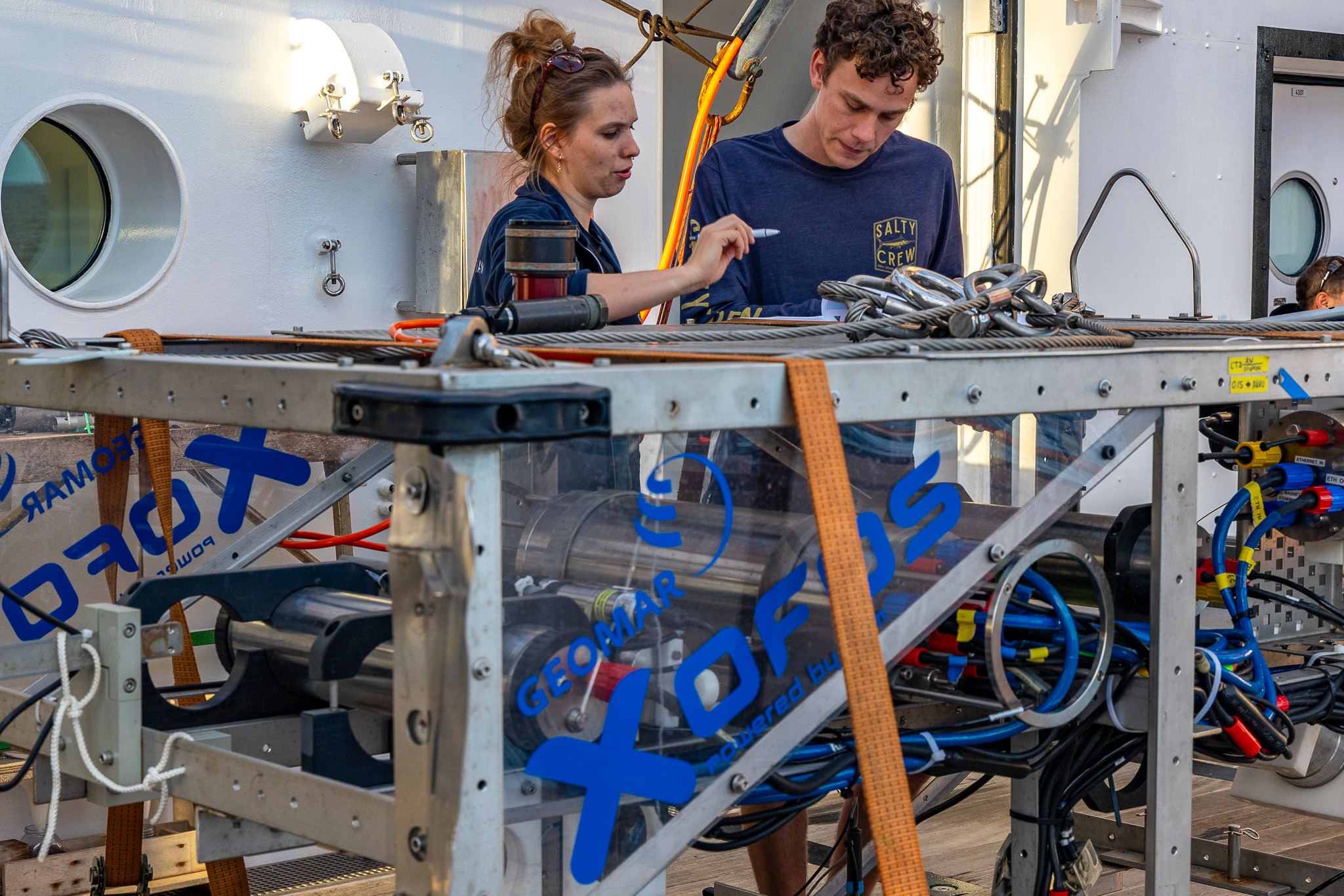

A completely different sort of data is image data. A true distinctiveness of MSM126 was the diversity of optical gear operations. With camera sensor-equipped gear such as the sea floor observation system XOFOS, the pelagic observation system PELAGIOS and the ROV PHOCA we had three platforms performing bottom and mid-water explorations – and generating terabytes of image data. And just as physical samples such as captured animals or filtered water, their digital equivalent needs proper curation and has to meet certain standards in order to be implemented in various research projects. To mention only one (which applies to all sorts of data), the so-called FAIR principles should be met. FAIR means that data should be findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable. Also, all the digitalized data needs to get a backup to ensure we have several safety copies. You see – you could say that the real work only begins after a sample is brought on board from the bottom of the ocean.

A true challenge during a research cruise, however, is the immense, stressful work and the reality of unforeseen situations. So, even if you have prepared the nicest protocols and most thoughtful working pipelines, people still might be too occupied with the hard work on the sea and structured data acquisition falls victim to this reality. For this case, it is a great advantage to have a dedicated position to keep an overview of our treasures – and for MSM126 I had this great honor. Okay, to be frank, I did this for the first time in my young scientific life and I think by the end of the cruise I’ve learned as much about data management as I have learned about handling difficult human interactions. Because as a data manager you have to be annoying. And to be a young, just-finished-her-master, female data manager which constantly pokes her older peers to do what she needs them to do requires a certain degree of resilience as well as creativity.

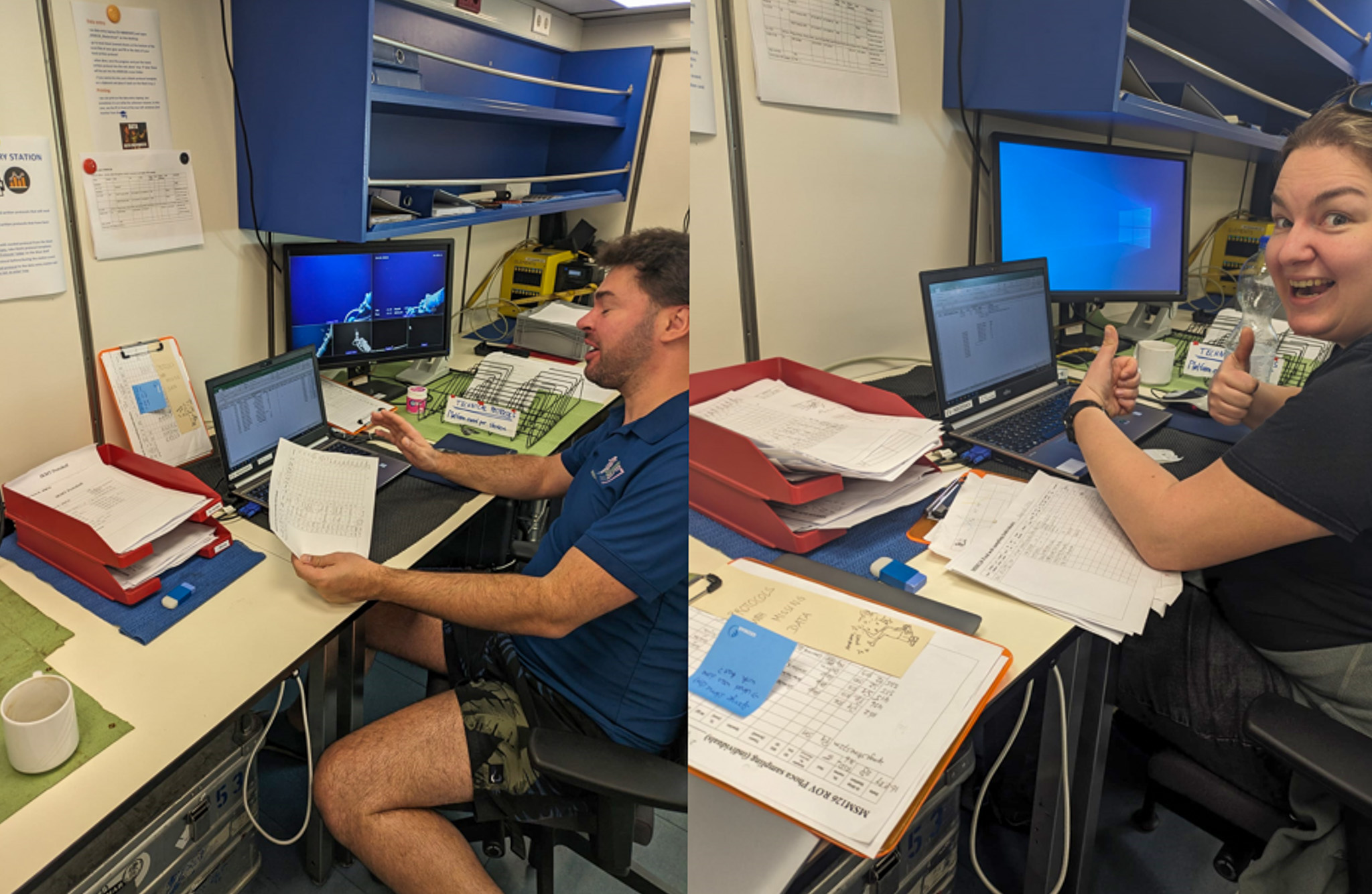

I guess here it comes in handy that I have a sort of dark past as a data manager… I am actually a trained biological oceanographer! And this can be quite helpful. First, I have background knowledge in quite a number of scientific actions here on board and therefore can understand what and how we need to keep in mind when it comes to data handling. Also, it helps a lot to decipher species names in hand-written protocols (sorry, needed to include this). Secondly, it gives you perspective on how difficult it is to be responsible for your own station, gear deployment, subsequent sample distribution and of course how all of this must be addressing your main scientific goal. Even though it should be obvious that everyone wants their data to be safe and sound, I still tried some ‘fun’ approaches such as over-the-top advertisement for our data entry station (“data entry is so cool and cured all my back pain”) or putting a monitor with ROV livestreams next to the data laptop to soothe the hardships of entering hundreds of lines of metadata into a giant Excel file.

I think we all did a great job regarding handling the huge amounts of ‘treasures’ we hunted during MSM126 and the only thing left to say for me is: do your data backups. Thanks for reading!

Sophie Valerie Schindler, Data manager (and secret biologist)