The GAME team in Chile is composed of Dario and Javier. We are currently conducting the main experiment that seeks to elucidate how artificial light at night (ALAN) affects the behavior of blue mussels. In Chile, we are working with the endemic and commercially important species Mytilus chilensis. However, our project also considers the effects of ALAN on the prey-predator interactions between blue mussels and their frightening enemy, the sea star species Meyenaster gelatinosus. We hope to find out whether the influence of light at night on the mussels varies with the presence and absence of a predator. This is possible, since it is widely assumed that circadian rhythms in mussels are driven by predator avoidance. Hence, mussels may only exhibit a certain biorhythm, if predators are present. If this is true, a light-induced change in the biorhythm could only emerge, when the mussels experience the presence of, for instance, sea stars.

But let us start with the beginning: Dario from Germany arrived at the end of April, while Javier came from northern Chile at the same time and we both had to start with getting used to living in Concepción. Our practical work is divided into a part that can be done at the University in Concepción and into another part for which we have to travel to a research station at the coast that is situated near the village Lenga. This is where we have a laboratory to set up our aquaria. This nice fishing village consists of only a few colorful houses on a narrow strip of land between the sea and the estuary of the Lenga River. It serves mainly as a recreation area for people from the urban center and is famous for its delicious empanadas (deep-fried turnovers with filling). Reaching it, however, takes around one hour by Micro – that’s what the locals call the small blue, crazy driving busses that go unfrequently and only during daytime.

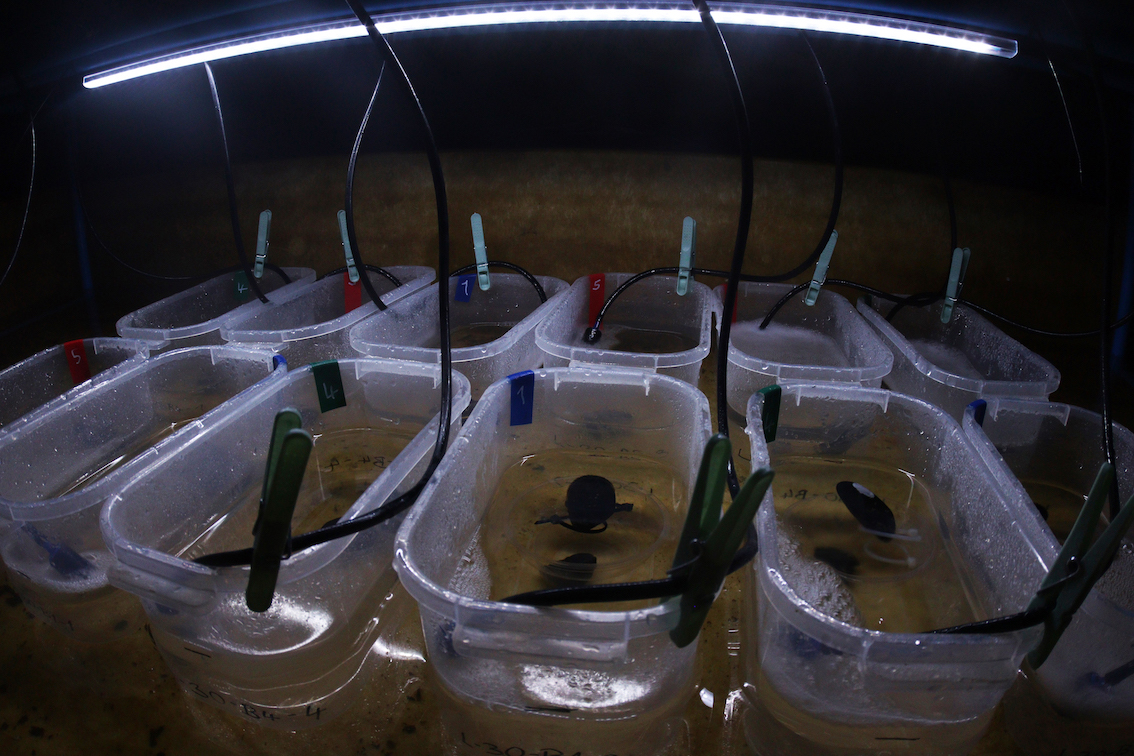

The station itself is quite basic, but it offers plenty of big trays on wooden shelves where we can place our aquaria. They belong to different treatment levels including a control group and are supplied with seawater and compressed air that both run through pipes at the ceiling. But other than that, we had to install pretty much everything else by ourselves and had to come up with our own ideas how to realize the experimental set-up. So, the first weeks of our stay went by quickly, since they were filled with construction work, hundreds of visits to our second home – the hardware store – and lots of other shopping trips to get everything we needed. Sometimes it was quite a hustle. We had to constantly rearrange the setup and had to change ideas because they didn’t work out the way we thought they would. However, we showed improvisation skills and team spirit! In this way, we also learned a lot about building laboratory setups and by now we have achieved most of our goals. Even though, not everything we had in mind in the beginning could be realized, we were quite happy and satisfied with the outcome at this stage. It was a rather complex system of multiple trays with different LED-settings that can simulate daytime light regimes and artificial light at night as well as two photo chambers. In addition, we put up some workspace for microscope analyses in a heated container. This very container also served as our home during the last week and will until this part of the experiment is over. This is because after sampling during nighttime, it is impossible for us to leave the station because it’s quite remote and even taxis will not drive here anymore. So, we stow the microscopes and settle down to sleep on our mattresses.

While all other GAME´22 members complain about the hot weather in their countries in our weekly Zoom meetings, we represent the “other part” of our global analysis. We work all day wrapped up in multiple layers of clothing at low temperatures, heavy rainfalls and strong winds during the Chilean winter. In addition, the lab is not heated and so we are always happy when the sun comes out during a break, and we can enjoy the fabulous view over the Bay. Then you can see hundreds of sea birds like pelicans, seagulls and cormorants trying to catch some fish, or, if you are lucky, a sea lion will swim by.

From the beginning of July on, we got help from Dario’s girlfriend: Maike! She is studying Marine Environmental Science in Oldenburg (Germany) and is also very interested in everything related to bivalves. Her bachelor thesis was already about the distribution of Cerastoderma edule in the German wadden sea. At the moment, she is doing an internship with our supervising professor in Chile. We are very grateful to have another pair of helping hands at our site, because, especially during our main experiment, we really have plenty of things to do.

To give you an idea about how our working days look like during the most intensive phase of our practical work, which lasts for about three weeks, we will explain it briefly. Everyday, we are processing several replicates, i.e. mussel individuals, of our main experiment. The fact that we have only two cameras available, limits the number of mussel individuals we can cover per day to 4. Basically, we start with monitoring the environmental conditions inside the aquaria such as the oxygen and the ammonia concentrations. Then, we need to re-start our 24-hour-time-lapse photography system after we finished the previous time-lapse monitoring of mussel activity. Next, we have to count the byssus threads that were produced by the 4 mussels during the last 24 hours and cut the byssal threads of another 4 individuals whose byssus production will then be measured on the next day. Since mussels need to get food to stay healthy, we must feed all mussels in lab every day with microalgae, except for those individuals that are in a starvation period. The starvation period is a preliminary step where individuals are not fed before each measurement. The objective of this starvation, in our case 24 hours, is that all individuals are in similar metabolic conditions when they are measured.

In the evening, we are recording the resistance of the byssus to mechanical stress, and take the lengths, and weights of the mussels we processed during the day. This is the moment, when we have enough time to save all the data to our computers. And finally, we are measuring the filtration rates of the mussels by counting the algal cells they consume per unit time. This done at midnight, since most mussel species show an activity peak during the middle of the night. We then analyze these data straight away – so mostly we are finished around 3 – 4 o’clock in the early morning. After a short but refreshing rest, we have to start our routine over again with new mussels.

To accomplish our daily routines, we have to be concentrated on not confusing the sequence of working steps. Furthermore, we need to make sure that each mussel individual is trackable, i.e. we need to know at any time to which experimental group it belongs, and we have to be aware to also not miss out any of the various measurements.

To evaluate the effects of Artificial Light at Night on the behavior of Mytilus chilensis, we selected four response variables: gaping activity, filtration rate, byssus production, and byssus strength. Gaping activity and filtration rates are important for the ecological fitness of mussels because both activities are essential for food intake and, hence, for growth and the formation of gonads. Byssus production and the resistance of byssus to mechanical stress are both relevant to ensure the survival of mussels, because the byssus prevents them from being washed to places with unfavorable conditions.

However, although we are already in the final phase of our experimental work, we still have some work to do before we will travel to Germany to meet with the other GAME teams of 2022 for the common analysis of the experimental data. We are excited to see how the results of our work actually look like. Even though it was not always easy, we are grateful to be a part of GAME for all the new experiences we have gained. Now we are already looking forward to everything that lies ahead of us during the time in Germany.