Hola and greetings from Vigo, Spain. My name is Jacob, and I have the somewhat unique experience of being an American student in the Biological Oceanography master’s program at GEOMAR, participating in this year’s GAME project. After months of waiting for international travel to once again be possible, I am happy to report that I have been able to go to Vigo in August. However, getting here certainly came with its own challenges with my passport raising red flags at the airport, but only as I was leaving Hamburg. The airline attendant took one look at my stars and stripes emblazoned passport and asked, “Are you flying home?”. “God no!” I nearly exclaimed, but I held my tongue and explained how Germany is my home now while passing over my residence permit to try and smooth everything over. From that point on everything went as normal, besides the anxiety caused by observing other travelers wearing their masks incorrectly or failing to social distance, but after a few hours and a bus trip from Porto, I arrived safely in Vigo.

Meeting me here was my team mate Nacho. We had the opportunity to meet back in March at the start of this year’s GAME project in Kiel, just when the coronavirus started to become an issue in Europe and all over the world. Little did we know then just how severe the coronavirus situation and resulting regulations would become, and after our group became fast friends during the first two weeks of the project, all of the students from non-German universities had to return to their homes on March 17th – two weeks before the scheduled end of the preparation course. Luckily, we were able to continue with planning our project and developing our experimental protocol through the various virtual platforms which have popped up as a boon during the pandemic. Admittedly, it was nice to still have something to work on during the time stuck at home, as it was one of the few things keeping me tied down to reality.

Despite being able to travel now, the coronavirus pandemic still plays a role in carrying out our project. The Spanish National Research Center for Marine Research (CSIC-IIM) where Nacho and I are working in collaboration with Drs. José Babarro, Ignacio Gestoso, and Eva Cacabelos, has understandably been careful to slowly open back up again, and we have had to wait for the authorization to work independently in the lab. However, delays are often common with doing science and in the meantime, we have been doing what we can from outside the institute.

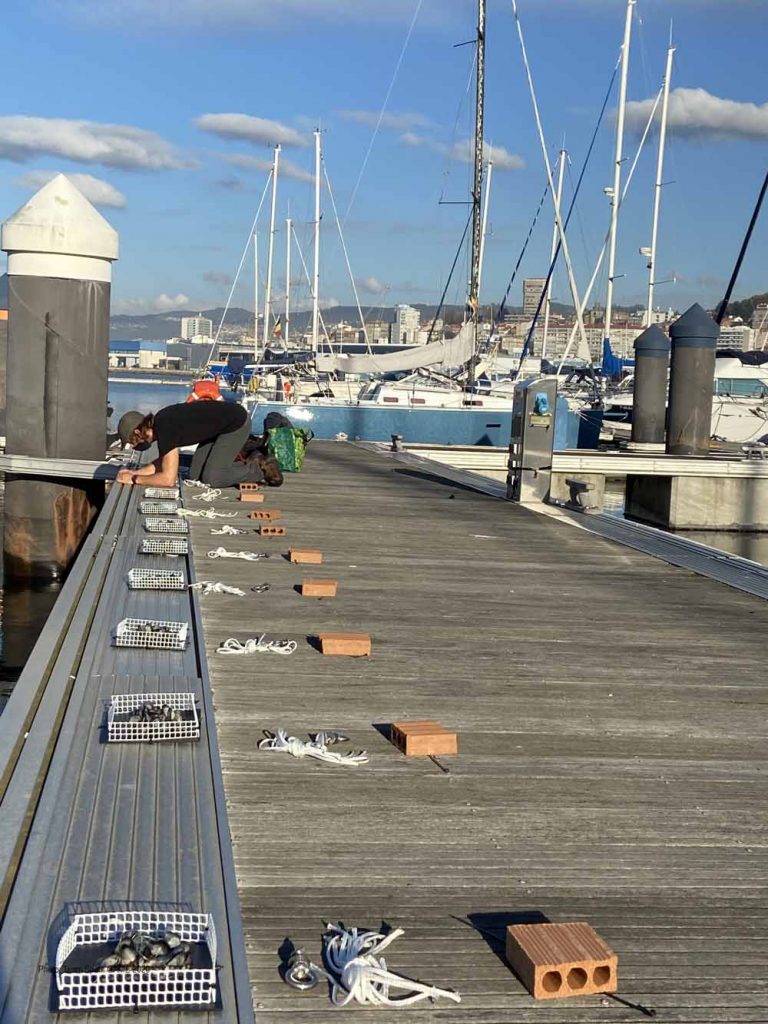

To study the effects of plastic litter on aggregates of mussels and associated communities, we collected mussels from the rocky shores of Vigo at the Playa de Samil, cleaned them, and placed them on PVC plates in the lab with a piece of plastic sandwiched in-between, which they will aggregate around. After they’ve formed stable clumps, we placed them in the sea for roughly 4 weeks. For this exposure phase, we’ve designed as a group a set-up which will house our mussel aggregates and keep them safe when they are deployed below the sea surface.

During the first month, Nacho and I have been collecting our materials, constructing our experimental set-ups from home, and obtaining permission from the Marina Davila to deploy our mussel aggregates from their docks. We have also been able to collect our first set of mussels of the species Mytilus galloprovincialis to determine the total surface area of each individual mussel belonging to the size class that we will use in our main experiment. The surface area is important for us to measure, as it will be the basis for the amount of plastic that we add to our aggregates. The method we are using to measure the surface area is one created by a former GAME participant and consists of painting one shell of the mussel red and carefully rolling in onto a piece of paper towel. With this print, we are then able to use imaging software to accurately measure the total surface area of the mussel.

Besides getting started on our project, the first month has been a good opportunity for me to get to know my new surroundings, enjoy the sunshine, visit the nearby beaches, sit for a drink in one of the many cafés, eat tapas, walk up and down many steep hills, and get lost on the winding city streets- which is the best way to get to know a city. I just find myself wishing I had paid more attention during Spanish class in grade school. Nonetheless, I’ve been able to pick up a few words and phrases here and there- most importantly to order food! I find myself constantly in awe of the beauty of Vigo and the surrounding area of Galicia, which looks much different than the mainland of Spain, being mostly flat, and looks even more vastly different than Kiel. For one, we get to experience tides here, and on my first visit to the rocky beach of Samil during low-tide, I felt like a child again while exploring the tidal pools and admiring the wonders held within.

With our authorization finalized, we began our work inside of the CSIC, and even with the remaining threat posed by COVID-19, the situation still feels relatively stable. We choose to remain optimistic and look forward to finishing our experimental work in December. More updates to come!

Hasta Luego!

Jacob Houvener