Author: Jaqueline Haußmann, Pictures: Jaqueline Haußmann

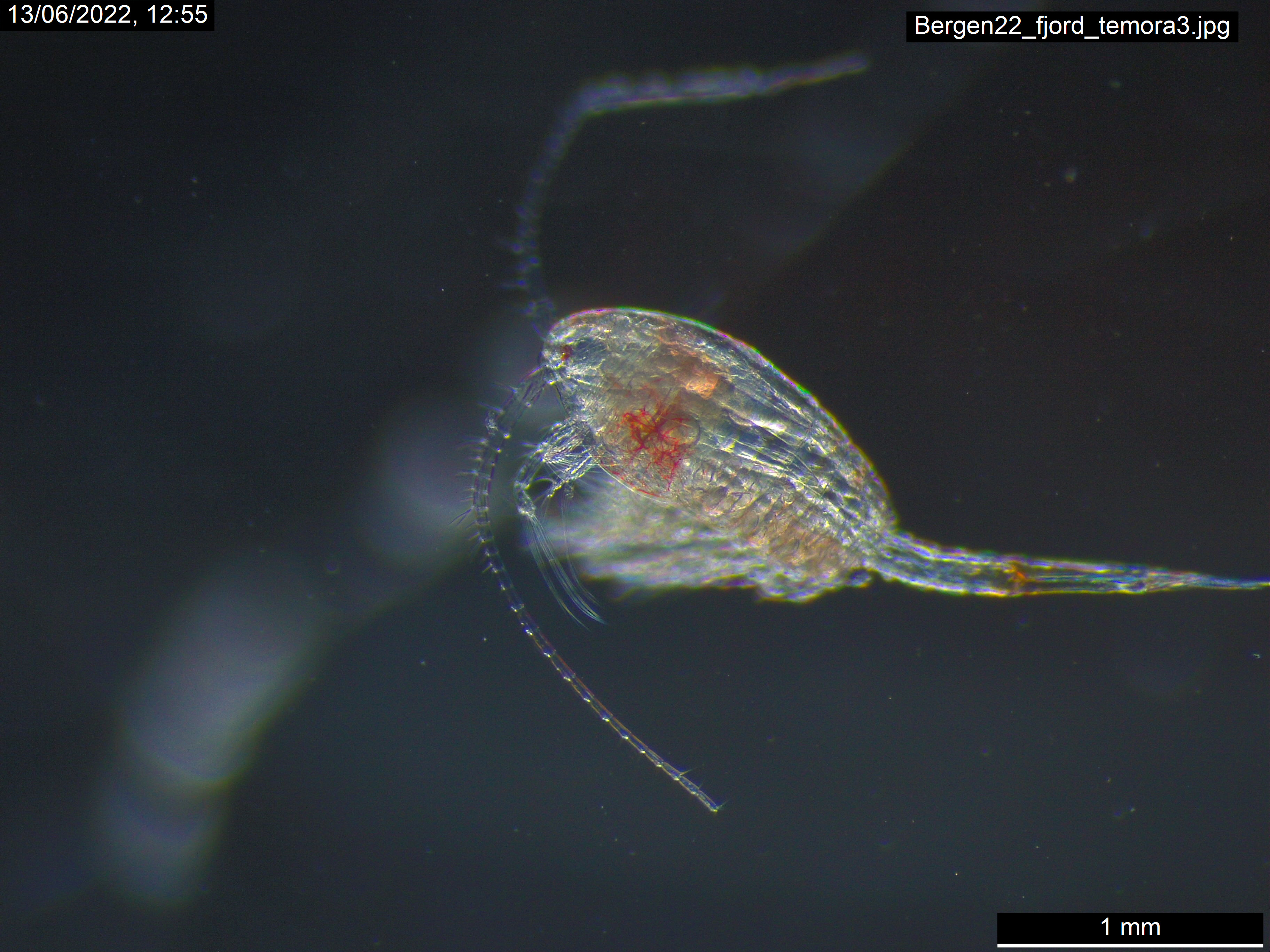

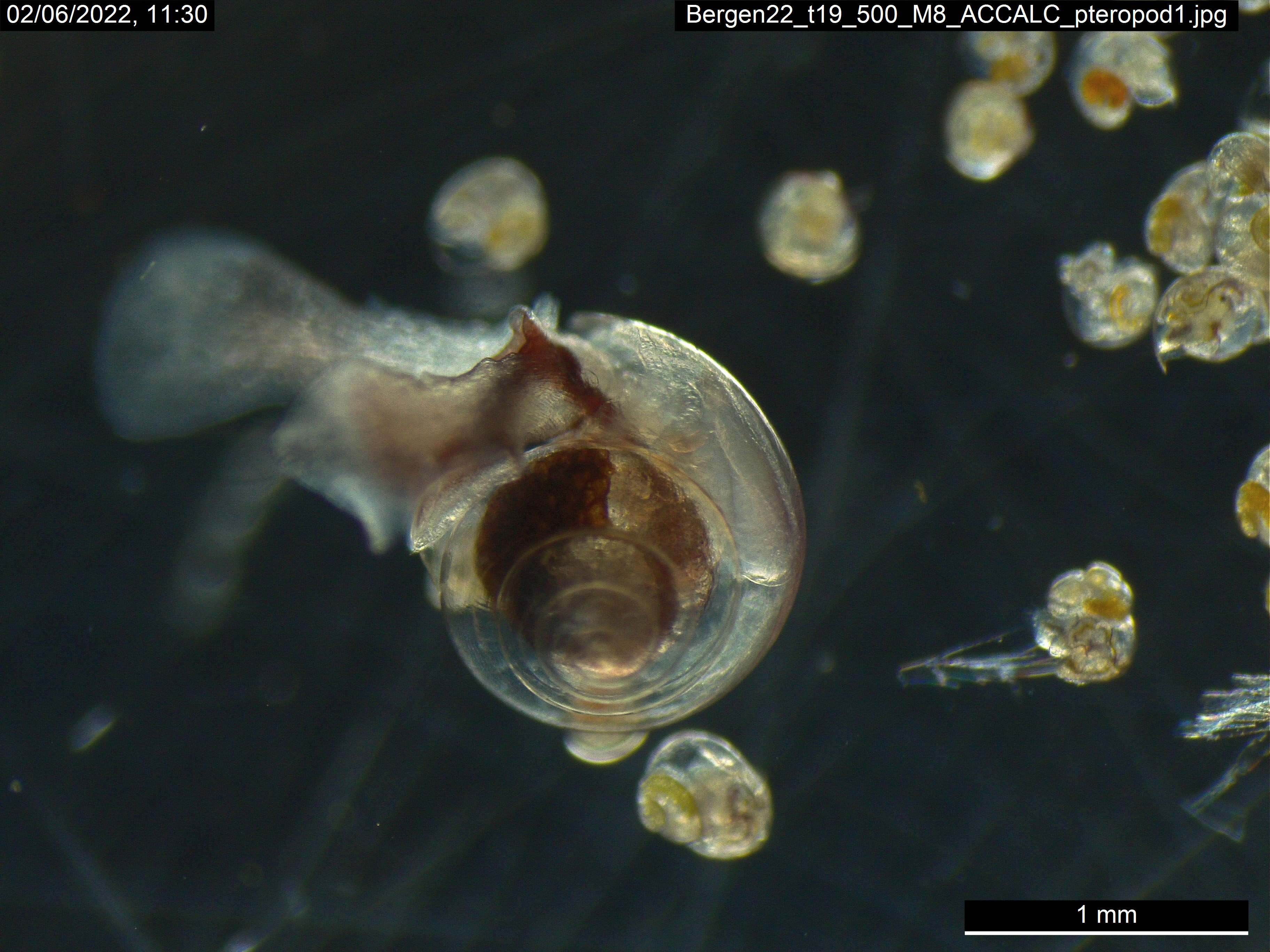

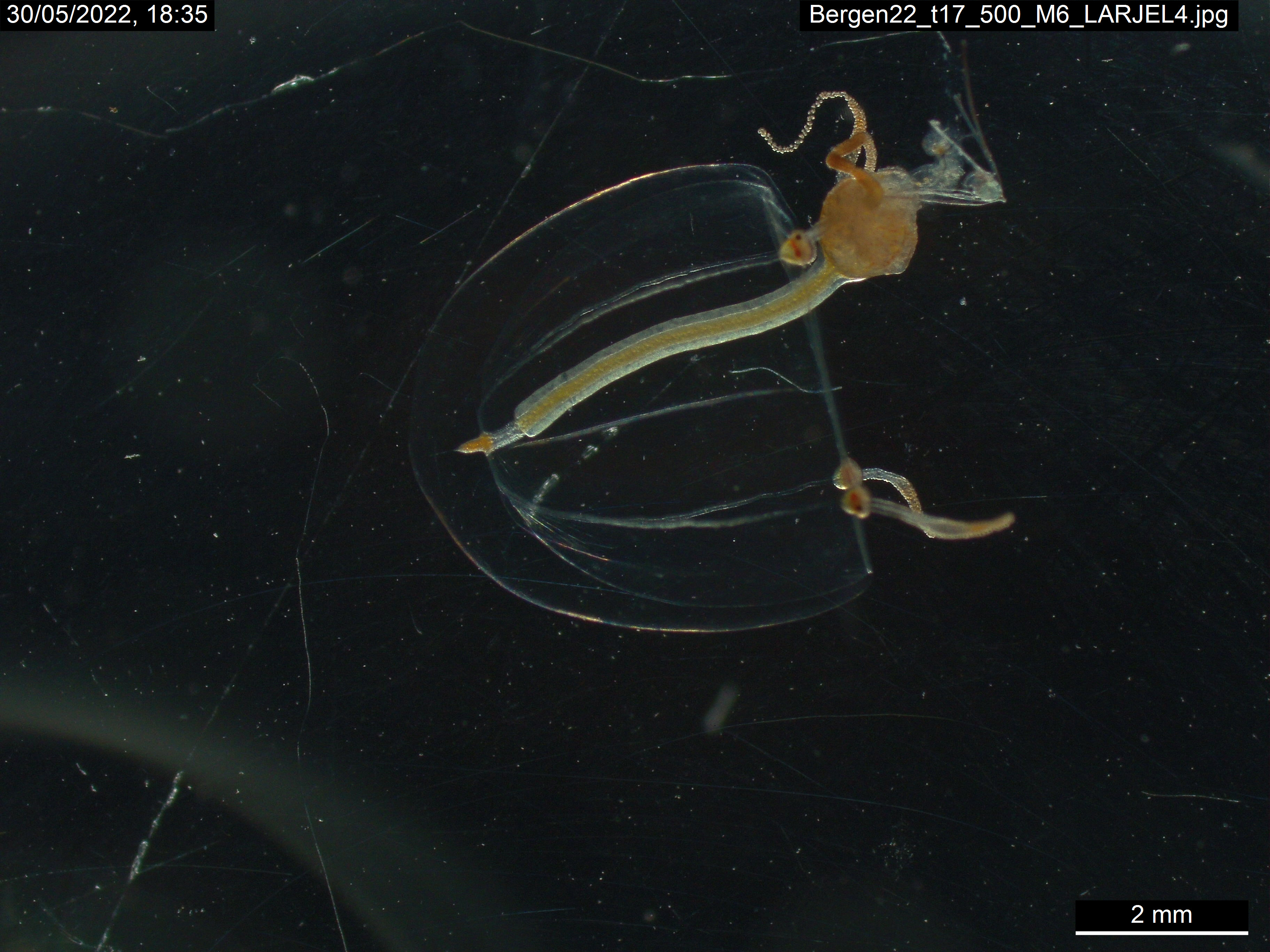

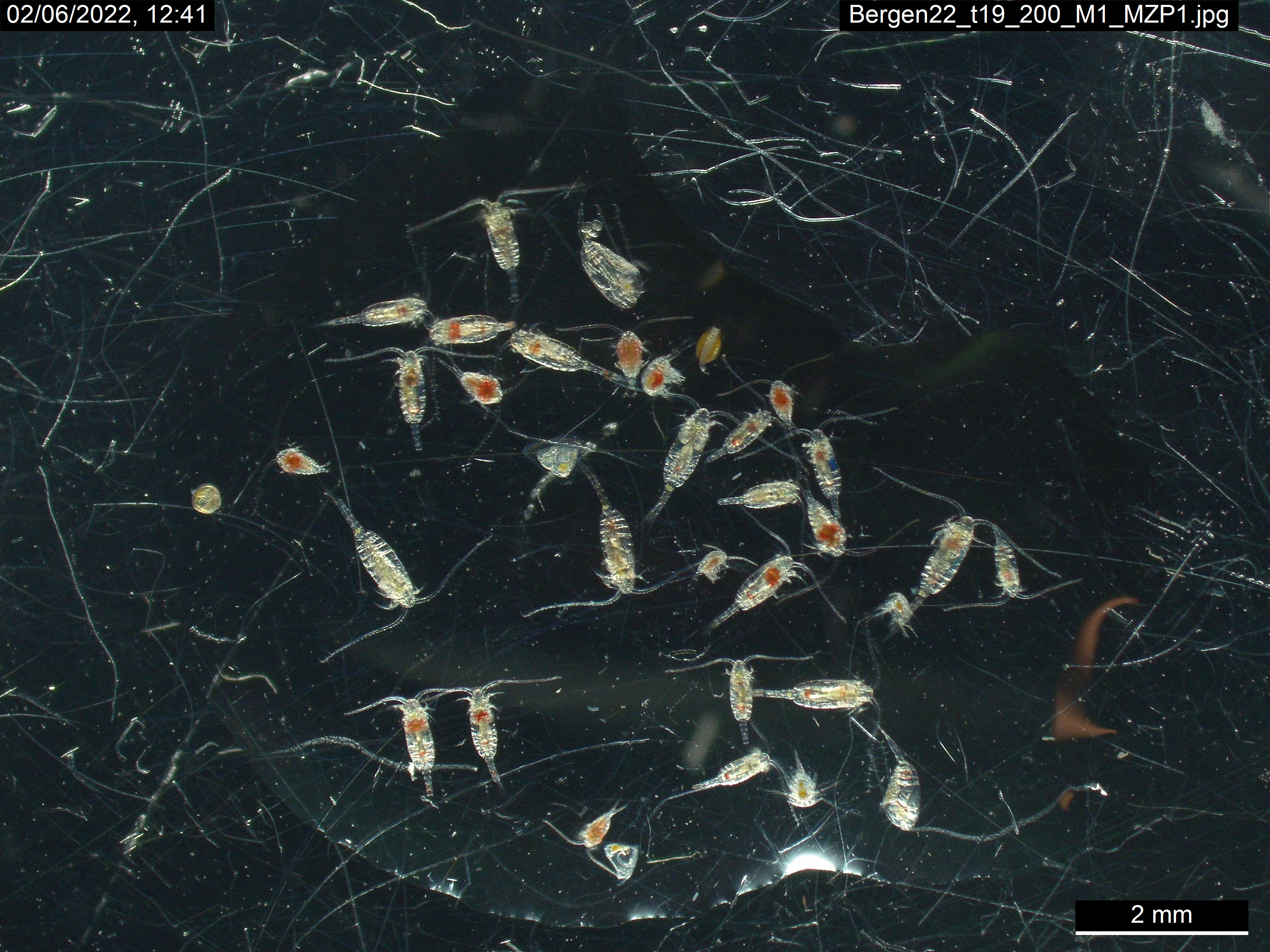

Click…click…click goes the sound of my counter. 41 so far, the number of individuals I have just collected and placed in a tiny drop of water inside a tin capsule. Another sample is ready! I put it in the according plate and note everything important about the sample. Off to the -80°C freezer for storage. Back to my scope, where a now empty petri dish awaits in the middle of the light. A few minutes ago, various species of zooplankton were swimming around in it. Copepods (small Crustaceans (1 & 2)) were running and jumping around. A polychaete (worm) crawled along the bottom. Tiny jellies (5) swiftly moved and pulsed. Appendicularia (6) (long gelatinous organism) twitched while trying to build a new house. And there was something like a snail flying around. A gastropod (4) or a pteropod (3)? I zoomed in to take a closer look at its shell: It coiled counterclockwise. “Pteropod!”, I exclaimed with excitement, as everyone gathered around me to look at the rare find. They are so beautiful when they flap around with their “wings”. The German name “winged snail” fits this marine pelagic organism quite well.

But back to the sample in the tin capsule that is by now preserved as a drop of solid ice: It will be analyzed for fatty acids (lipids) back at GEOMAR. The problem with fatty acids is that they hate warm temperatures, light, or oxygen, which makes them troublesome to work with. The good thing is that we can get a bunch of information once the extensive process of analyzing the samples is complete. Different groups of algae (one of the food sources for zooplankton) have different fatty acid compositions. By measuring these same molecules in the zooplankton, we can track what they have been feeding on over the last days. So, our aim is to better understand trophic interactions within our mesocosms. In turn, we can also find out how nutritious these zooplankton are for higher trophic levels such as fish and later humans.

But to get all this information, we have to sit down at our scopes for several hours to separate the organisms into different subsamples. For some samples we need to pick more than 120 organisms one by one to have enough biomass for later analysis. This takes a lot of time! Therefore, we need to work together as a team, share tasks and don’t confuse samples when giving them to the next person. This might be one of the reasons why our microscopy lab seems to be the most crowded place in the whole station especially on “picking days”.

Time to dive back into this completely different world we see through the scope, loaded in organisms with fancy shapes doing funny movements, and enjoy the beauty of the ocean.

Copepod adult 1

Copepod adult 2

Gastropod larvae

Pteropod

Jellyfish

Appendicularia

Examples of mesozooplankton 200-500µm

Examples of mesozooplankton >500µm