Olá da Madeira! The island – a green paradise in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean – has been home to us for almost three months already. How the time flies!

We are Lara and Karo, one of 8 teams that currently conduct experiments all over the world as part of this year’s GAME project. Lara is a Marine Biology student currently enrolled at the University of Rostock and she is collecting data for her master thesis within the project. When she heard about GAME from her professor, she knew she had to be part of it! Karo is studying Biological Oceanography in Kiel. She found her passion for marine sciences quite recently and has never lived close to the ocean on beforehand. It was a dream of them both to join this project!

This year’s aim is – like in the previous years since 2021 – to investigate the effects of artificial light at night (or ALAN for short). We want to see how this phenomenon affects macroalgae in their ability to photosynthesize, grow and defend themselves against grazers. After an intense planning phase in March, during which we decided on the design of our experiments, we were more than glad to leave cold and grey northern Germany behind and escape into the sunny, subtropical climate of Madeira.

Finding accommodation was not easy, but in the end, we found a nice flat in the capital city Funchal with (almost) an ocean view! More than this, we have a balcony where we’ve enjoyed many lengthy weekend breakfasts.

We had an enjoyable first week when we settled into our flat, scouted the city and tried to figure out the bus system, which proved to be kind of complicated, since there are so many different bus companies here. One thing we learned very quickly, though: walking on this island requires strong calves. Madeira is hills…hills…and more hills. This is why you hardly ever see local people walking here – sometimes you get funny looks when you are doing a typical German “Spaziergang” (which is more like a hike over here), and you really have to watch out not to get run over by a bus or a car.

Then, we finally met the team of the Marine and Environmental Science Centre “MARE”. In our first meeting, we sat together with our supervisors (who are all former GAME participants!) and discussed how we could make our experiments here successful. Everyone was excited and motivated to get our project started!

Not long after, we made our first trip to the laboratory where we are conducting our experiments together. It is located in Quinta do Lorde, a place on the easternmost part of the island. It is close to the peninsula “Ponta de São Lourenço” which offers stunning views over the rugged coastline of the volcanic island. This part of the island is very dry and it almost feels like you have stepped into a desert – quite the contrast to the rest of Madeira, which is a lush, green paradise.

It is also the perfect spot for investigating ALAN, since it is very isolated and therefore mostly uninfluenced by nighttime illumination. Hence, the marine life here is not already adapted to light at night. The only downgrade is: the lab is located quite far away from Funchal, where we live. Most days, we have to take a bus that takes the scenic route and drives 1.5 hours along the coast, up and down the hills. At least we are rewarded with pretty ocean views during the drive – or we go for a little nap, especially after a long day in the lab. Thankfully, we can sometimes catch a ride in the car with our supervisors.

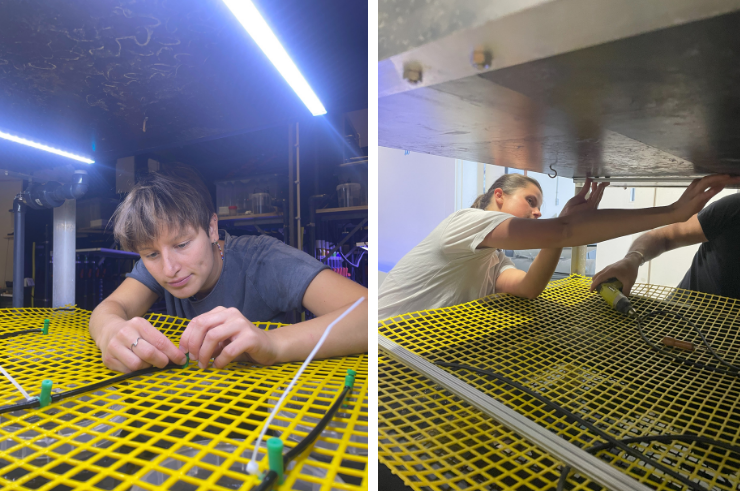

In the first weeks, we worked hard to build up our experimental set-up. Thanks to the great work of former GAME students, our lab is already equipped with most of the materials that we need, so we could quickly set up a flow-through system to supply running water to our algae. But we celebrated too soon: The complete water system of the lab had to be cleaned with bleach due to some pesky epiphytic growth and that meant that we had to re-do the flow through system again from scratch. We patiently cut tubes, and more tubes and connected them with little plastic suppliers, which let out filtered seawater to each of our 72 experimental tanks.

To give our algae as much light as possible, so that they are able to happily photosynthesize, we decided to order more LED lamps. One thing we did not anticipate: Madeira is located in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, around 1000 km from the European coastline (the African coast is actually closer!), so equipment can take a loooong time to arrive. We were lucky that our lamps arrived “only” 3 weeks later, but already we faced the next challenge: connecting our lights to the control unit, with which we want to regulate the light intensity that our algae will be exposed to, proved to be more difficult than we had previously thought. However, with the help of the lab technician Patrício we quickly found a solution!

When we weren’t diligently building our set-up, we spent our days snorkelling in different places on the south coast of the island, looking for algae “candidates” that we could use in our experiments. Easier said than done, because the waters around Madeira are depleted in nutrients and large macroalgae are rare to find. We quickly decided on using Halopteris scoparia, a brown macroalgae that is quite abundant in the upper subtidal and therefore possible for us to collect while snorkelling. Another (particularly interesting) candidate is Rugulopteryx okamurae, an invasive brown alga, that has first been introduced on the north coast of Madeira in 2021 and since then spread rapidly – it is even growing on the pontoons in the marina outside our lab. It could be especially interesting to investigate how this species reacts to ALAN in comparison to native algae.

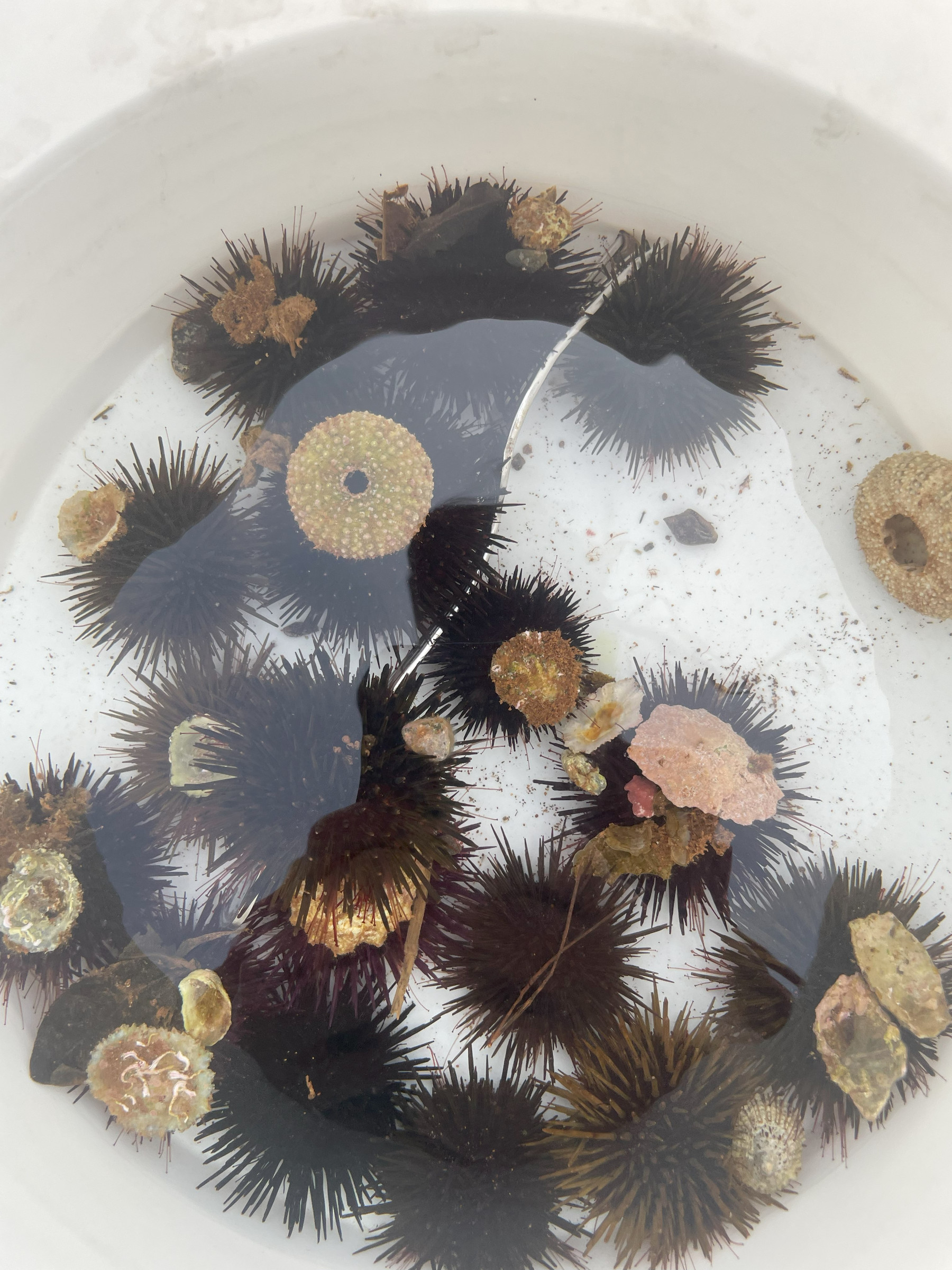

Since we want to investigate how ALAN affects the defence capacity of our algae, we also had to find suitable grazers (=algae eaters). Our options were less than ideal: Should we use sea urchins (even though they are very hungry and consume our algae in too large amounts) or intertidal snails (even though this makes less sense ecologically, because our algae come from the subtidal). In the end, we decided on the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus, which we can easily collect in the tide pools next to our lab. Did we say easy? – To get the hang of how to sample these little algae eaters took some blood, sweat and tears. Equipped with forks and buckets; after waiting for low tide to arrive, we wade into the tide pools and try to gently (or not so gently) persuade our sea urchins to come out of the holes in the rock that they like to sit in. We always take good care not to injure or stress them too much, but some unfortunately have already met their fate.

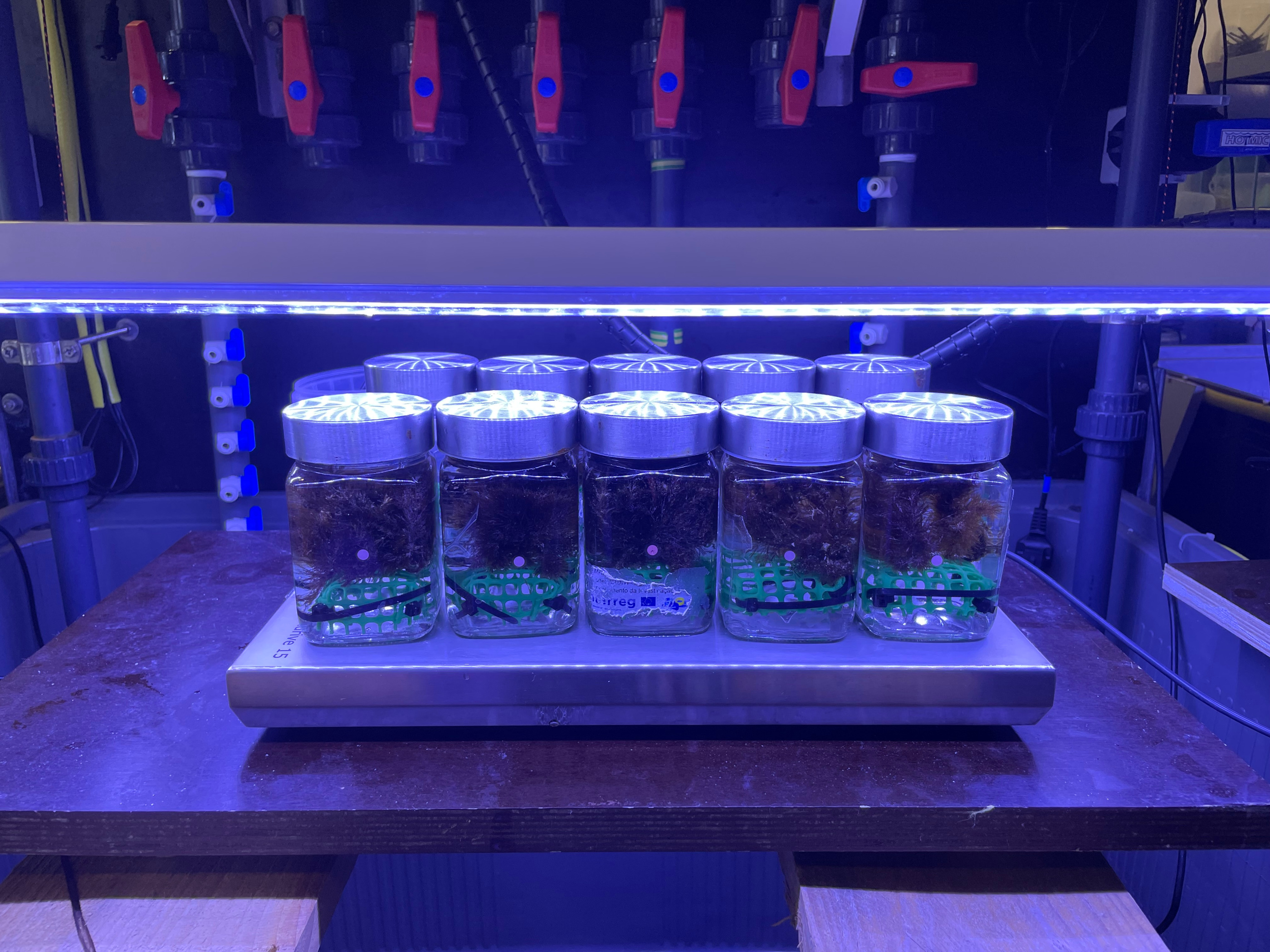

Before we could start with the main experiments, we had to test a few things. For instance, how much and when the sea urchins eat and how much the algae photosynthesize. To find this out, we carried out some pilot studies – more or less successfully. During one of our pilot studies all our sea urchins mysteriously died, probably after some contamination of the water. In addition to this, our method for measuring the oxygen production initially did not work, because the oxygen values we measured did not stabilize and photosynthesized waaaay too slowly despite looking perfectly healthy. After many hours of trial and error, we fortunately found a way that should allow us to accurately assess the oxygen evolution. For this , we increased the light intensity to help the algae photosynthesize more quickly and also got a multi-position magnetic stirrer where we can put multiple of our containers with algae on simultaneously. A little magnetic bar keeps the water in the containers in constant motion, resulting in more stable oxygen measurements.

Furthermore, we have another nice tool available here. It is a PAM, which is short for Pulse Amplitude Modulation. Behind this rather complicated name lies a technology with which we can assess how well our algae are absorbing sunlight for photosynthesis and ultimately determine their health status. Because no one in the institute had used the device before, we had to do a lot of headache-inducing reading (the 200-page manual is not easy to understand) and carry out some test runs to get prepared for the measurements. Our weekly meetings with the other GAME participants became crucial for discussing challenges and brainstorming solutions together – so far this project has been a huge learning curve for the both of us.

Our lunch breaks we share with the lizards. Fun fact: there are more lizards than mice on Madeira! They are called Madeira lizards (Teira dugesii) and they are endemic to some of the Macaronesian islands. They are very curious creatures – especially when we unpack our food. They sometimes even like to jump on our feet, but you have to watch out that they don’t crawl inside your backpack, and you accidentally take home a new pet.

When we are not in the lab, we also know how to have fun (not that being in the lab is not fun). Madeira is an island full of amazing places and activities, and it’s a hiker’s paradise! There are a lot of different routes to explore, very famous are “levada” walks here. Levadas are old, narrow water channels that wind through the mountains. They were constructed to carry water from the misty mountains down to the drier parts of the island to water the crops of the farmers. You can walk along these levadas and enjoy the views over the island!

Besides doing a lot of hiking and training our calves, we have spotted some dolphins, explored different beaches, and even got swept up in the European Championships fever. Since Madeira is Cristiano Ronaldo’s birthplace, people here (young and old) are fans, and we joined the locals cheering for the Portuguese soccer team. Of course, we also had to try Madeira’s famous “poncha”, a traditional drink with rum and fresh fruit juice – typically lemon, orange, or – our favourite – maracuja. Another drink is Nikita, which is a mixture of pineapple juice, ice cream and beer. It tastes… well… interesting, as Karo’s face in the picture shows.

Madeira’s climate is perfect for growing all kinds of tropical fruits and other plants. What people keep as house plants in Germany, grows here in ditches next to the road, or in the size of trees – Monstera leaves get almost bigger than oneself! We also tried some fruits here that we have never seen before in our life. Our flatmate’s supervisor even has avocado trees in his backyard, which we sometimes get a share of – a luxury we will sorely miss back in Germany.

Another thing we learned here: you can never trust the weather forecast. In Funchal, situated on the south coast, the weather is usually pretty dry and sunny. However, it’s a different story for the North coast, where it rains more frequently, and temperatures are cooler. But even here on the sunny south coast, you never know what to wear. You could burn under the African sun or in the next second freeze from the wind, especially in the evenings, when the sun is already down. The onion-principle (a German favourite) really proves best.

We have been really enjoying our time here so far and we are sure by the end of September we will not want to go back to Germany. We have finished the first experiment and are soon starting the second one, we are excited to see what happens!