This year’s Finnish GAME team is made up of two German students, Saskia and Florentin, who are studying at the universities of Tübingen and Stuttgart, respectively. Our project is based at the Husö Biologiska Station on the beautiful Åland archipelago. It consists of thousands of small islands that are located in the Baltic Sea west of the Finnish city of Turku. Only the larger islands are inhabited, while the capitol and largest settlement of the Åland isles is Mariehamn where about 30 000 people live permanently. Husö Biologiska Station is located on the island of Bergö, which is about 40 km north of Mariehamn. The island is very sparsely populated and mainly covered by woods, which are full of blueberries and mushrooms. The next place to find a supermarket is Godby, a car drive of about 15 km away.

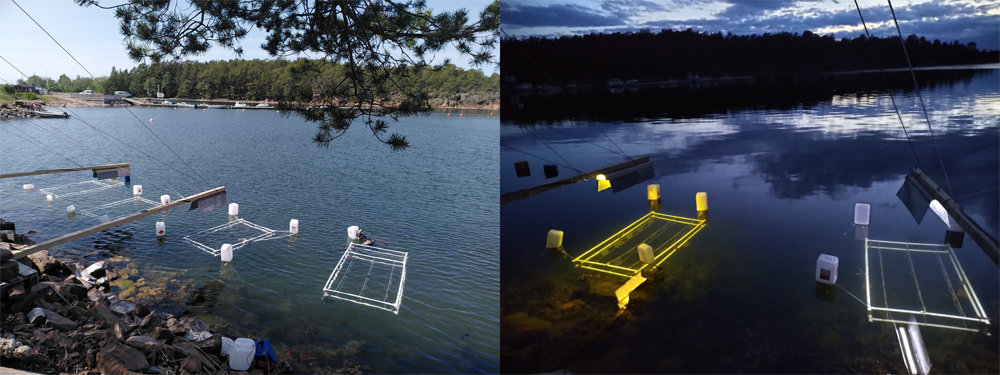

Similar to the last two GAME projects in 2021 and 2022, we want to improve the understanding of how artificial light at night (ALAN) can affect marine organisms. This year, however, things are a bit different as we are focusing on the influence of ALAN on communities of sessile organisms on coastal rocky sea floors. Therefore, we are running a field instead of an aquarium experiment with all the different joys and difficulties this entails!

Even though Åland and the Baltic Sea may not seem as exotic as some of the other GAME locations, it is actually a very fascinating place for the experiment. First of all, the Åland islands have white nights in summer, meaning that it is never fully dark for a couple of months. This makes us suspect that organisms here are used to the presence of light at night. But does that also hold true for the artificial light that is, for instance, emitted by street lamps and, which has a composition that is different from that of sunlight?

Additionally, the Baltic Sea is connected to the North Sea only through the very narrow Kattegat and receives most of its water from rivers and rainfall. Therefore, it has in large parts a very low salinity in comparison to most other seas and oceans. On top of that, it is a geologically young sea, as it was covered by glaciers during the last ice age about 10000 years ago. Since the glaciers’ started to melt, its salinity has repeatedly varied drastically, leading to the current state of a brackish sea with a smorgasbord of freshwater and marine species living side by side.

However, despite its marvels, the low salinity of the Baltic Sea also makes some things more difficult. As the project should focus on marine organisms to make the results comparable to those of the other teams, it was important to find a location that is occupied by species like blue mussels, barnacles, or the bladder wrack. However, these organisms cannot be found in the bay at which the biological station is located. Therefore, we spent our first month in Finland leafing through sailing maps and monitoring reports, calling a lot of people (sometimes speaking English, more often a wild mixture of Swedish and English) and driving around the archipelago. After some very beautiful road trips and the discovery of a very promising location for the experiment, we learned that both the shore and the water are often privately owned on Åland, and not always by the same people! We had to search for the waters’ owners and needed to make more phone calls after that! Luckily, the groundkeeper of the biological station seems to know everyone on the archipelago and helped us out a lot.

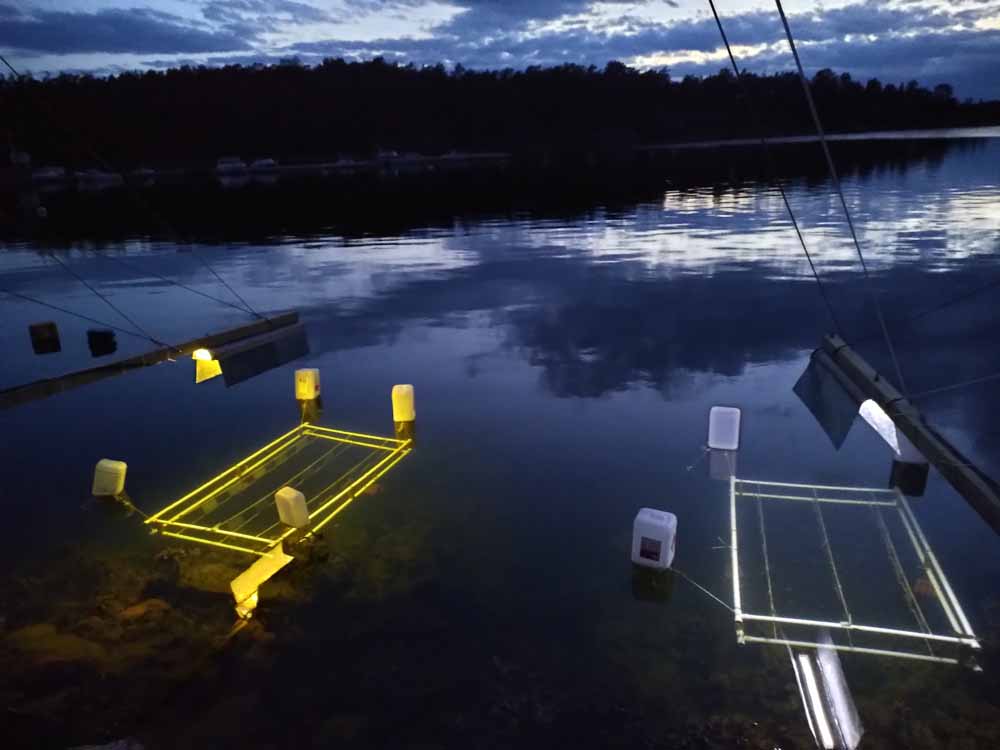

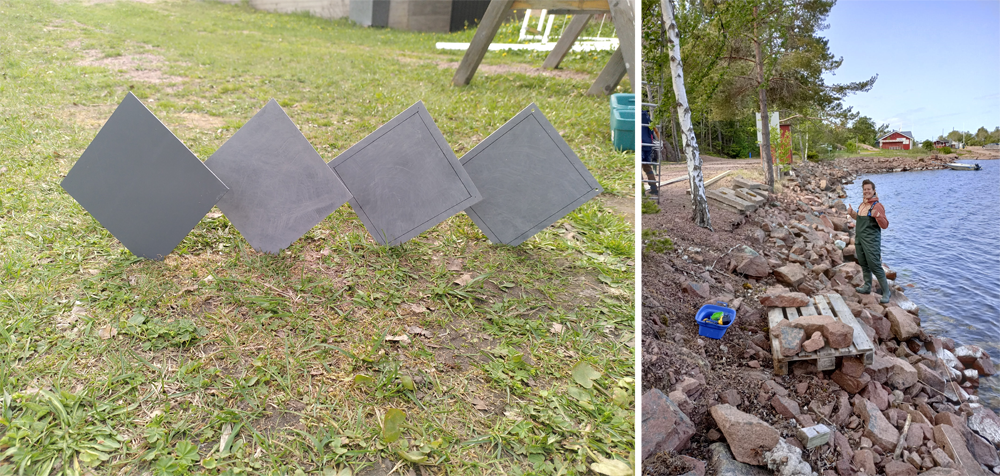

Parallel to the location search, we also built our experimental setup and learned the Swedish names of our equipment. We could find most of the material that was needed to build the set-up on Åland, but often at a much higher price than on the Finnish mainland. Therefore, Christian Pansch-Hattich, our local supervisor who is living in Turku, graciously became the GAME delivery driver whenever he came to work on the station. Thank you again!!

Eventually, the location was secured, the set-up was built and the experiment could be launched as planned by the end of May in the guest harbor of Hamnsundet, half an hour away from Husö station.

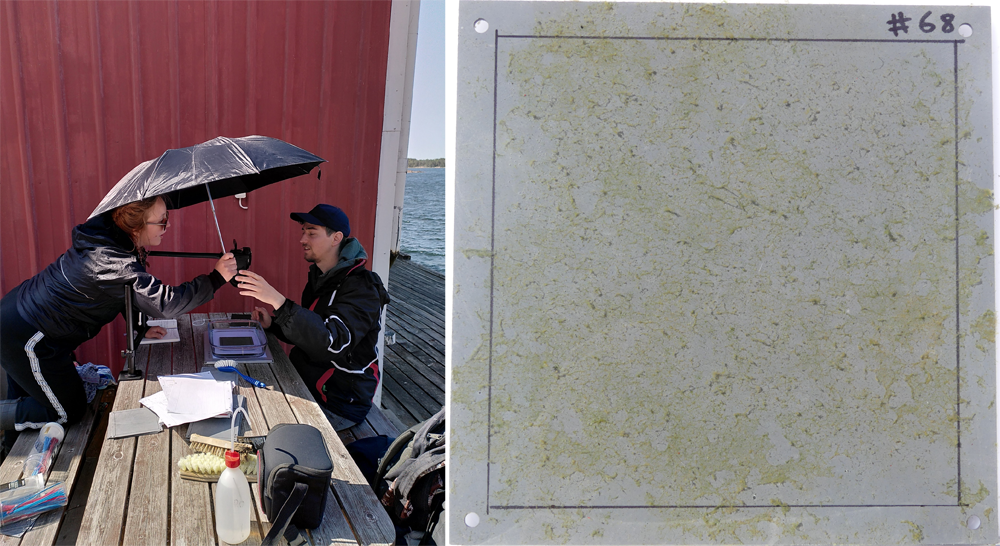

By the end of June, it was time for the first sampling and we spent a week examining all the settlement panels we had deployed one month earlier under a stereomicroscope and taking pictures of them. Due to the cold water and overall slower growth rates in the low salinity environment of the Åland archipelago, the main ongrowth on the panels was an algal film consisting of various microscopic organisms. Since our main interest lies on larger organisms, which can be observed by the naked eye, and which can more easily be identified to the species level, we considered this sampling rather as a first familiarization with the communities and the Baltic benthic ecosystem than as an opportunity to collect data. We were excited to see which organisms could be observed at the next sampling!

After waiting for another month, it was time to sample again. Unfortunately, the weather was not as friendly as during the first sampling. We protected ourselves and our equipment from the rain showers with a large tarpaulin. By the third day, strong winds threatened to rip the tarpaulin away and we relocated under the porch roof of a nearby Sjöräddning (sea rescue organization) building.

The weather could not dampen our moods, and during the second sampling week, we found many tiny baby cockles (Cerastoderma edule) on the panels, organisms that could be observed by the naked eye! However, they were only passing guests. Since adult cockles live buried in sandy bottoms, we expected them to disappear again from our panels during the coming weeks. Alongside the cockles, we observed the green alga Cladophora sp. in large abundances. It formed quite long filaments and turned the panel surfaces into green forests.

Then, one month later, during our last sampling, the picture had changed again. As expected, the cockles had disappeared, but now tiny blue mussels (Mytilus trossulus/edulis) and barnacles (Amphibalanus improvisus) could be observed. These are true hard substrate inhabitants that would have stayed on the settlement panels, if we hadn’t removed them from the water after this last sampling event. The Cladophora filaments had become shorter in the meantime and were largely overgrown by diatoms and cyanobacteria.

In between sampling events, we got the chance to help out with various ongoing projects at the biological station and to learn more about marine biology research. It felt like the days never had enough hours to do everything we wanted. We started learning to drive small motorboats and helped taking water samples in the outer part of the archipelago as part of a long-term monitoring of the condition of the Baltic Sea. A PhD student needed extra hands when collecting charophytes and we learned that even some green algae can turn red when they grow closely under the water surface. And we got the opportunity to be involved in the process of setting up the mesocosm facility, a large temperature controlled tank system with a permanent inflow of sea water from the bay, creating an intermediate stage between open field research and closed off aquarium research. Mesocosms are often used to model heatwaves and climate change predictions, and we also helped collect mud crabs for the first experiments in the new system.

And whenever there is some free time, we can simply grab one of the station kayaks and go exploring the bay, walk through the woods and look for eagles or hang a hammock in the forest and listen to the birds.

Hejdå och vi ses!