A most unusual and unforgettable field experiment has come to an end. A study in which we learned as much about how we deal with uncertainties and perceived threats in a situation never experienced before, as it has taught us about the possible responses of one of the most productive ecosystems in the ocean to environmental changes. It felt like a continuous stream of previously unimaginable challenges – logistically, scientifically, socially and personally.

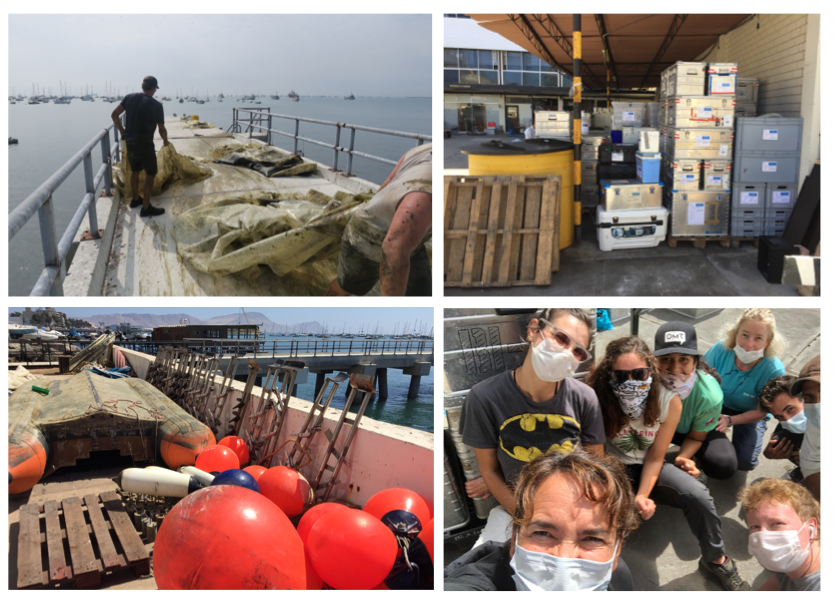

Logistically, it was a contest from start to end. It all began with a serious test of our patience. Being all excited and eager to jump start the experiment, we went through two long and frustrating weeks in wait for our containers to be cleared by customs. What a relieve when the trucks loaded with research equipment arrived in La Punta. Well, we could set up our instrumentation, but it took another week until various extra permissions were finally obtained, needed for the last container carrying all our consumables to be cleared. In the meantime all groups had arranged their working space and were ready to go.

With three weeks delay the experiment finally started and – aside from some nasty technical problems during deep-water addition, which took a couple of extra days to be by-passed – quickly started to build up momentum. The work routine was just about to settle in when it was suddenly interrupted by the Corona shadows looming over Peru. Although the number of COVID-19 cases was still low compared to most European countries, the Peruvian government took strong and decisive action from one day to the next, closing its borders and implementing a country-wide quarantine and curfew. Luckily, thanks to special support letters by IMARPE and the German embassy we were able to continue our work, within certain restrictions. The biggest blow to our research came a week later, however, when we were informed that our labs at the Club Nautico and the harbour of the Escuela Naval will be closed in the next hour. We used every minute of that hour to get as much of our lab equipment and our boats out before lock-down. Already the next day, the equipment was set up in the breakfast room and bedrooms of our hostel Villa La Punta (thank you Vilma and Luisa for allowing us to change your hostel into a research lab) and at IMARPE, who permitted us to continue using their facilities. The group’s spirit of determination and endurance at this point was just amazing.

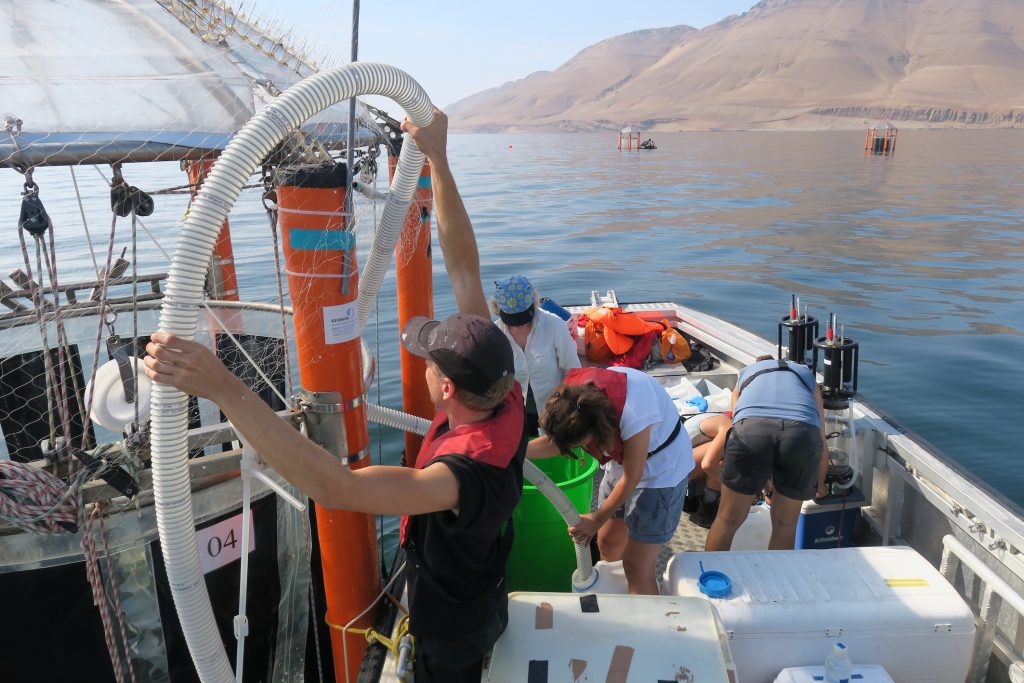

With all the restrictions, continuing our experimental work was a daily hurdle run. But to everyone’s (including my own’s) surprise, we managed to carry on until day 35, the originally planned final day of sampling. Unbelievable under these circumstances and something that we can all be proud of. What followed was a powerful final sprint of all those still on site. All the equipment was collected in IMARPE’s backyard, packed in precisely the order in which it arrived in Peru, and stacked in big heaps ready for shipping. In a tour de force the mesocosms were recovered in multiple steps over several days with the help of the research vessels IMARPE VI and BIC Humboldt. Along with our working boats Wassermann and Rita and the deep-water collector, they were transported to a warehouse for interim storage until our technical team can enter Peru again to get everything ready for return shipment. Hopefully it won’t be too long.

Scientifically the biggest challenge was the lack of group discussions and data presentations. It felt like a blind flight, where the experiment progressed without a good overview of how our enclosed ecosystems developed. With the start of the quarantine our IMARPE colleagues were forced to stay home, which also meant they couldn’t participate in the e-mail exchange. On the positive side, the few results which became available during the study look very promising, with strong treatment effects both for the light and the deep water addition treatments. The biggest highlight for me was that the larvae of anchovy and grunt fish introduced half way through the experiment thrived well and were collected in large numbers in all mesocosms at the final day of sampling. This was the reward for months of hard work by the IMARPE aquaculture team, supported by the CUSCO fish team, who managed to keep adult anchovies in culture, get them to spawn and the larvae to grow to a size where they could be introduced into our mesocosms. With this we should be able to follow trophic transfer from phytoplankton all the way up to fish. This alone is an amazing success. I’m excited to see all the results unfold over the coming months and learn about the responses of this hugely important upwelling ecosystem to ocean change.

Socially the situation was exceptionally difficult. With the start of the quarantine and curfew, it was impossible to come together as a group. Social interaction took place only within the subgroups living together in the various accommodations. This made it very difficult to keep a group spirit alive, which is so vital in a study like this. And the restrictions imposed by the Peruvian authorities in response to the COVID-19 pandemic were perceived very differently from person to person. In this situation it was pointless to continue deciding and acting as a group. It was essential to make room for everyone to decide for themselves and count on the support of the others in handling the situation. And I’m impressed how the people helped each other getting through these difficult times. With the fantastic support of the German embassy we were able to secure seats on several of the repatriation flights as soon as they started, so that those in need could get home as early as possible.

Personally this was the most demanding and stressful experience as a research campaign leader I ever went through in my professional life. Ensuring everyone’s safety and well-being was the number one priority. However, a lot of mental stress was caused by the physical isolation due to the quarantine and curfew and by the uncertainty about how and when we would be able to get home. For some the best way to deal with this was by isolating themselves, for others it was by continuing our research as good as possible within the imposed restrictions. Finding the right balance between providing a perspective on how to continue our work, and giving mental support to those who chose to step out, was one of the most difficult parts for me. Any group message sent to all took the risk of being misunderstood in one or the other way. What made it easier to get through these difficult times, I believe, was that by continuing our research we shared the feeling of having a sense of purpose, a sense of direction, as Anna phrased it so nicely in the previous blog entry. Indeed, positive highlights for me were the days when I could join the group going out sampling at the mesocosms, as it gave me the illusion of freedom and normality.

I am very grateful to all who helped us getting through these challenging times, too many to be named here. And I am glad that all participants have made it home safe and sound, many of us still going through another 14-day quarantine. We all had to pay a high toll to COVID-19, but I think we made the best of an extremely difficult situation. I look forward to coming together again in this group, enjoying the scientific rewards of this extraordinary study and catching up on some of the social events that we all had to do without during this campaign in COVID-19 times.

Ulf Riebesell