This morning, while packing my suitcase for the upcoming KOSMOS 2020 experiment in Perú, I read that there is currently a red tide in front of Miraflores (Lima, Perú), and this brought warm memories from our last year’s cruise to these waters.

Last year, I was on the magnificent research vessel Maria S. Merian celebrating Christmas and New Year’s Eve far away from home. We had experienced oceanographers, chemists, ecologists and marine biologists on board and we were all excited to investigate the processes that govern upwelling and productivity in this highly productive region of our ocean. We saw lots of birds, seals and even whales, especially close to the coast. But we also saw plenty of fishing vessels, capturing tons of the very famous anchovy. The anchoveta fisheries off the coast of Perú represent 20% of the global fish catch in an area that is less than 1% of the world’s oceans. “Why is this upwelling system so efficient?” was one of our main research questions.

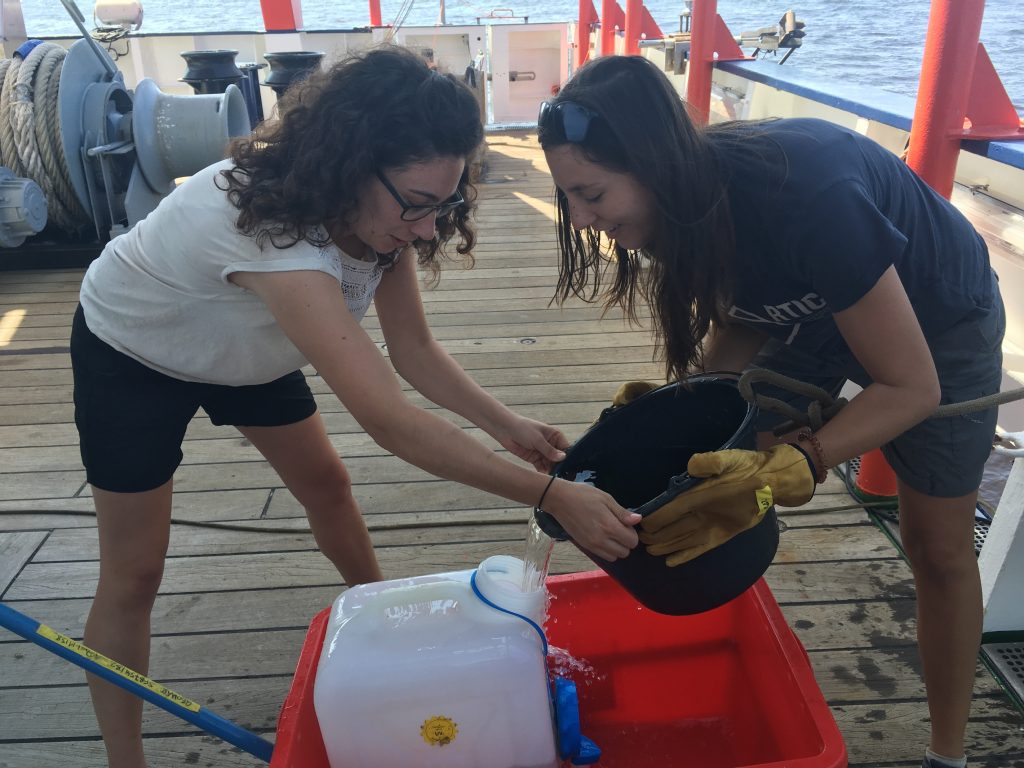

We did five on-shore off-shore transects perpendicular to the coast and it was immediately obvious that most of the biomass was accumulating close the coast where the upwelling was stronger. But there were also some interesting outliers, huge amounts of the little red crab Pleuroncodes at the surface far away from shore, and a huge red-tide that we baptized as “the blob”. The blob was extensive but patchy, and it was not so easy to capture with our regular sampling, so Allanah and I decided to make it happen. We went to the oceanographers controlling the CTD and we asked them if we could monitor the fluorometer values for a peak in the photosynthetic pigment Chla (a proxy for algal biomass). We talked to our luckily flexible cruise leader, Holger Auel, and he agreed to ask the captain to stop the boat as soon as we were on “the blob”. After several zig zags, we managed. We were in the middle of the red tide and the CTD was ready to go down to sample it. I really wanted to know which organisms was responsible for such a coloration. Unexpectedly as we were about to lower the CTD into the water, the patch of water on the starboard side of the ship turned clear blue, while the red patch remained on the backboard side of the ship. We couldn´t ask to turn around the ship again, but we were also not willing to miss such an event on our sample collection after so many efforts. Our solution was an easy one. We took a simple bucket to the opposite side of the ship and we lowered it down into sample the red soup.

I was so excited when I saw the dinoflagellate Akashiwo sanguínea moving around rapidly with its flagella under the microscope. This species is a typical suspect in harmful algal blooms.

Today, a year later, we are already analyzing our taxonomy data in combination with the environmental variables recorded at each sampling station to try to decipher the combination that makes this red-tides appear and the impacts they have on the food web structure. We luckily have a new Master student, Silvia, working on it. She will also join us next week in Perú, to investigate how will the Peruvian upwelling ecosystem react to upwelling intensity shifts due to climate change, this time from land with the mesocosms in the water. The good thing of this upcoming expedition is that this time we packed in our luggage, not only our equipment and safety shoes, but also everything we learned in the 2017 KOSMOS campaign in Perú, as well as all the knowledge from the MSM80 cruise on board R/V Maria S. Merian. Hopefully this means that we are better prepared to make this experiment a success. However, if one thing became clear from the beginning is that to work in Perú the thing we will need the most of is: patience.

Mar