Ahoi!

My name is Paulina and I am a bachelor student at the Christian- Albrechts-University Kiel. For the second time in my life I get the possibility to participate in an Alkor cruise organized by Jan Dierking from the “Evolutionary Ecology of Marine Fish” Group of GEOMAR.

The cruise is a very good experience for me, not only to get insights into the different sampling methods applied at sea but also to learn which biological questions can be addressed with the different samples. A very good example for this is the collection of the fish otoliths collection during the current cruise, as part of the fish sampling that takes place on board (Here are links to two posts from our cruises last year in case you are interested to learn more about the goals of the work on board, and about fishing for science ).

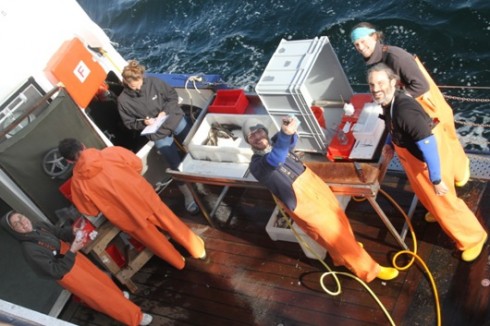

Sampling fish. Photo: P. Urban

Photo: Measuring and sampling fish on board Alkor.

Otolith…What is it? The otoliths are the inner ear bone structures of almost all fishes. Every species has its own individual shape and structure. Otoliths are responsible for gravity, balance and movement. Each fish has two pairs of 3 different otoliths (left and right). We collect only the big ones, called statoliths. More than that, every species has its own shape of otolith, which means that otoliths found in the stomachs of predatory fish can help identify their prey species.

Since 1989 cod otoliths are collected in the long-term data series to which the current cruise is contributing. Worldwide, otoliths have been collected for even longer then this, in part since the 19th century, as they form tree-ring like structures that can be used to determine the age of a fish. More recently, such stored otoliths have been used for genetic analyses to assess long-term changes in population structure, and micro-chemical analysis to assess migration behavior of the caught fish.

Usually otoliths are made of calcium carbonate in the aragonite form, but sometimes within one specimen we find “crystal” otolith, where calcium carbonate is stored in form of vaterite. This is shown in the photo at top of this post for otoliths of cod (Gadus morhua), where the left one is crystalized, found only rarely, whereas the right one is a “normal” otolith. Additionally to calcium carbonate, proteins are also laid down in otoliths and locked away so well that they do not degrade even long after the fish has died. This protein contains information about the diet over time and thus feeding ecology information.

In my bachelor thesis I am going to extract these proteins and use a method called compound specific stable isotope analysis (CSIA), to identify the prey types consumed by the fish. Once established, this method could be used to go back to the past by extracting ecological information from historic otoliths stored in collections. E.g., using our own otolith archive, an important aim is to understand whether there have been changes in what cod is eating over time to better understand changes in cod numbers and in its condition.

Below: How to get to the otoliths? Cut on the two third part of the head, and break the head in 2 parts using pressure. The otoliths should be right in front of you! (all photos: P. Urban, except photo at top of post, P. Urban and C. Dransmann)