Deutsche Version siehe unten

Marcel Rothenbeck, AUV Team – GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Germany

We have been at sea for 40 days now. As expected, all we see around the ship is water as far as the eye can see, and every now and then a group of red-footed boobies is flying around the ship. Outside on deck it is humid. According to the forecast, the weather should have deteriorated today, too bad for a dive. But the weather forecast was wrong this time.

In the hangar and in the front part of the working deck it is rather quiet. On the one hand, because the ROV – connected to the ship via a long cable at the stern – is working on the seabed. On the other hand, because many of the scientists collecting sediment samples with the box corer and the multicorer are still asleep after a long, busy night.

As I step from the hangar, where the boatswain is sitting during his coffee break, onto the working deck, I hear a cricket chirping. It has been doing so since we left Port Hueneme almost six weeks ago and everyone wonders what it does for a living here. On the way to the quarterdeck, I pass some of the equipment that was launched during the night and finally two containers. The door of the second container is closed with wood, above the slot for the air conditioner’s supply air some prankster has stuck a sign saying “Do not throw in hot ashes”. The original air conditioner had stopped working a few days ago. When I get to the door of the container on the seaward side, I have to pull hard on the door, because the replacement air conditioner, which is holding up valiantly, creates a slight vacuum in the container.

From inside I am greeted by a gush of cool air and loudly blaring “Do they know its Christmas” by Band Aid. Inside the container, three people are busy preparing a device for the next dive. My voice doesn’t stand a chance against the Christmas classic from the stereo above Anna’s head. She smiles and turns the volume down. “The mission for Tiffy is on the server” I say. Anna nods and then continues to go through the checklist lying on a narrow table to her right. A screen lights up in front of her, displaying Tiffy’s data. Karl also lifts his head and nods. He is holding a line that Torge is carefully stowing, turn by turn, in a metal container in Tiffy’s nose, or shot open, as a sailor would say.

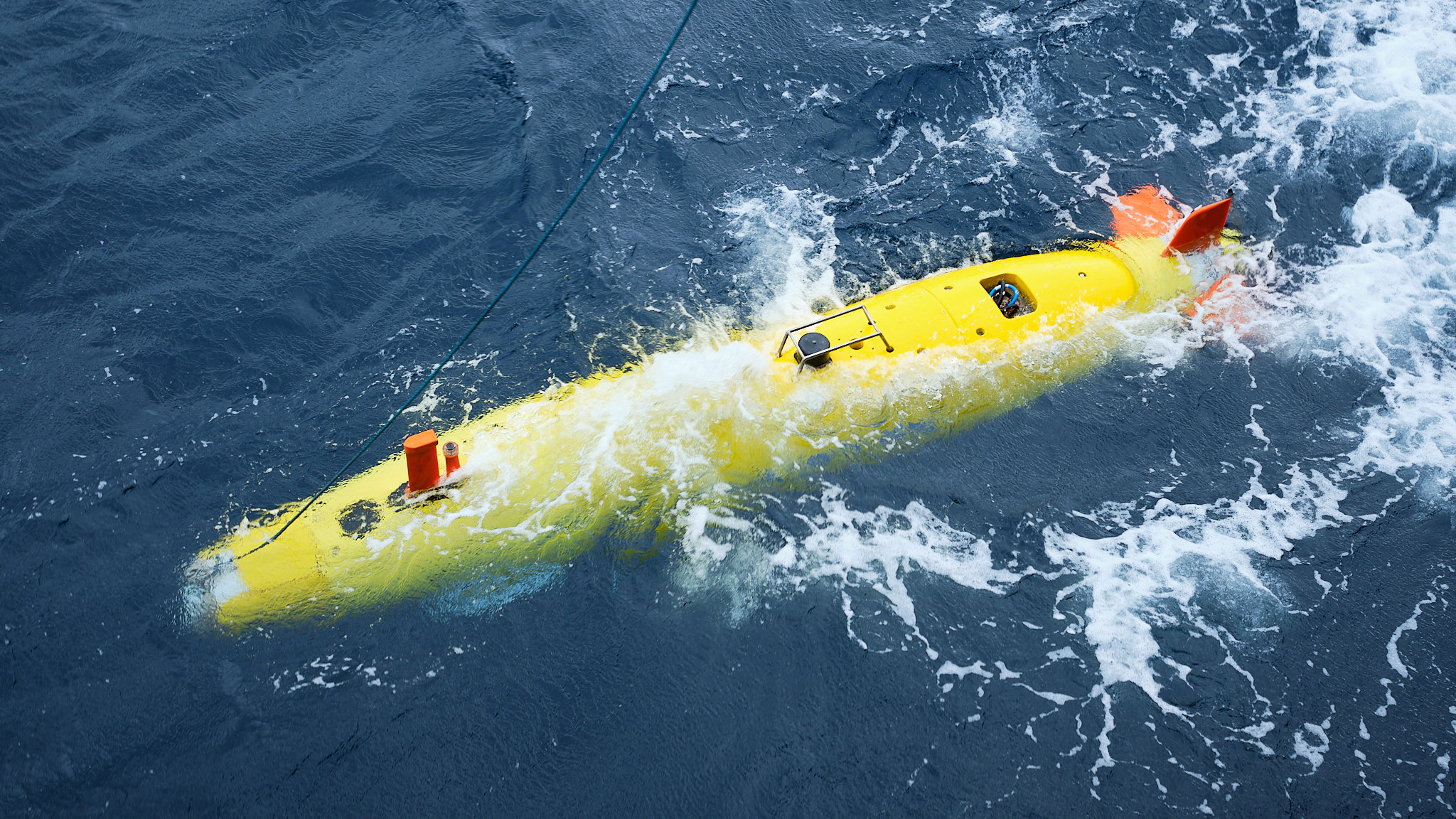

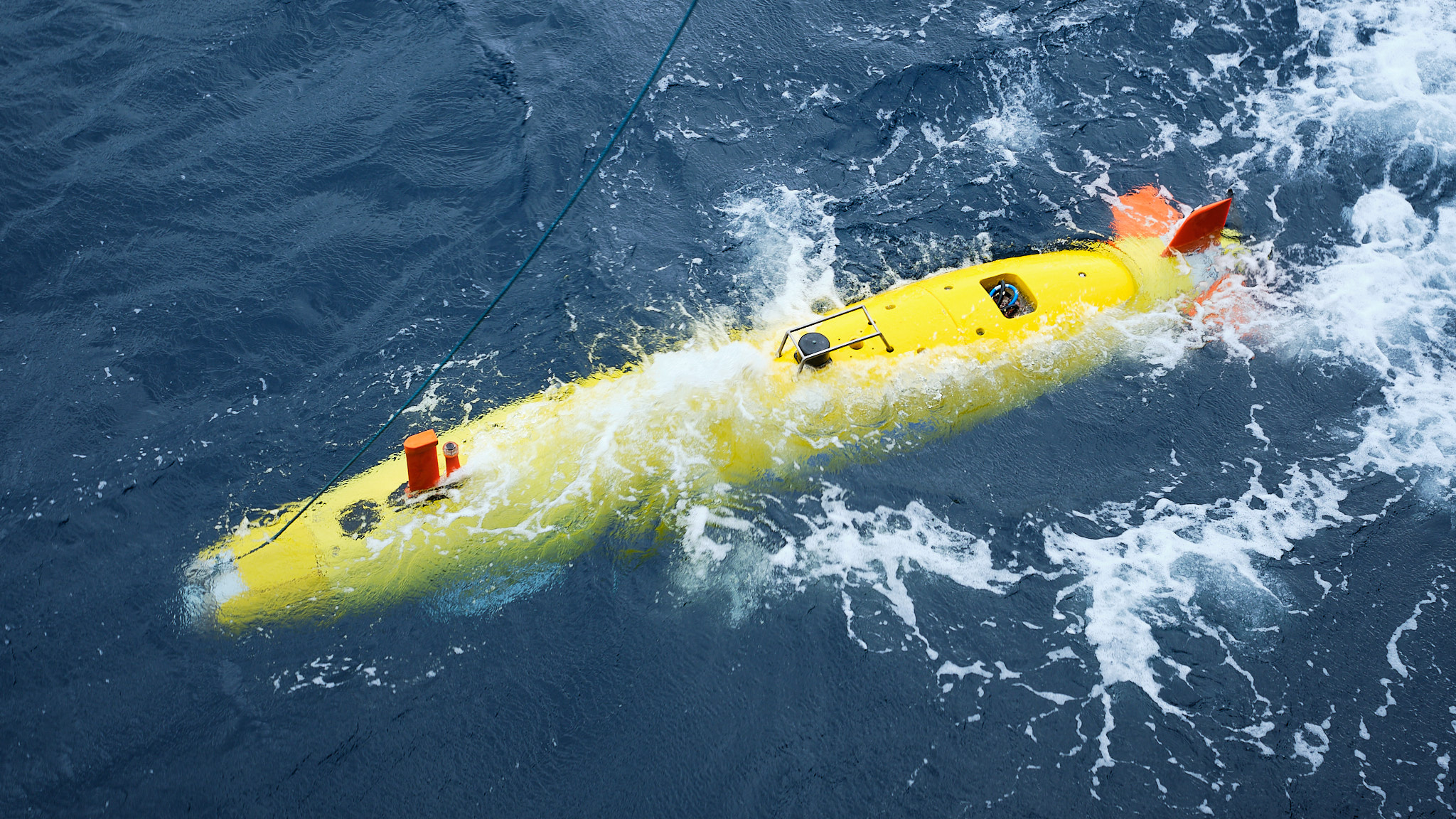

But who is Tiffy anyway? Tiffy is an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV). Her official name is AUV ABYSS, but her nickname has somehow stuck. It is shaped like a four-metre-long cigar, weighs almost 900 kilograms and can dive up to 6,000 metres water depth. She is also bright yellow. She has already been diving through the depths of the oceans for 14 years, which is a stately age for a deep-sea AUV. Tonight, she is scheduled to descend to a depth of 4,500 metres and follow a pre-set course five metres above the sea bottom. At this distance, the seabed is optimally illuminated by the flash of Tiffy’s camera.

Meanwhile, the next Christmas hit is playing in the container. To my left, Anna continues to look at the screen and checks whether Tiffy’s sensors are working properly and delivering good values. The side-scan sonar, with which Tiffy records the topography of the seabed, has already been tested. The camera comes last. There is a checklist that is followed step by step.

“We’ll upload the mission at the very end, okay?” asks Anna without taking her eyes off the screen. I nod. The mission is Tiffy’s work programme during a dive, so to speak. It contains every step Tiffy has to take on the way from the water surface to the seabed, on the seabed and back to the surface. The current mission will last 19 hours. The AUV is expected to cover a total of about 100 kilometres. The mission specifies exactly where its next waypoint is, how fast it should “fly”, which sensors should be switched on or off and how long it has to reach the next waypoint. If it takes longer, the dive is aborted. The safety programme then assumes an error and lets Tiffy drop an emergency weight. This makes her lighter and she climbs up. But this should only happen in an emergency.

All dives on this expedition will use the camera and side-view sonar. Tiffy is supposed to take so many photos in different areas that they can be stitched together to a large photo mosaic on board using a special software. This is much more useful for the researchers than the 50,000 individual photos taken during a single dive. While the camera shoots a photo every second, the side-scan sonar continuously scans a 100-metre-wide strip of the seabed (50 metres each to the left and right of the AUV). This data is also later processed into an overview map.

In the container on the working deck, Torge has already packed the rope neatly into a box at the tip of Tiffy’s nose and connects the end of this line to a block. He then presses the block into the opening provided above the box so that it fits positively with the nose. He runs his hand over the block and nods with satisfaction. “You can trigger it now, Anna,” Torge says. After a few seconds, the clack of the latch can be heard, releasing the buoyant block. Check.

The block is triggered when the AUV has resurfaced and is at the right distance in front of the ship, ready to be captured. But for this to happen, Tiffy must first reach the surface. If everything works smoothly during the dive and Tiffy has reached the last waypoint, she receives the command to surface. Then she pulls her nose up and spirals towards the surface. At a depth of 4500 metres, the ascent takes about 75 minutes. As soon as Tiffy has reached the water surface, she uses GPS to determine her position. She sends the coordinates to us in the container so that we know where the ship has to go for recovery. Once the ship is close enough to Tiffy, we send her a message to unlock the floating block. This releases the rope, which the deck crew of the FS SONNE then catches with a throwing hook.

In the container, the checklist has already been completed to the extent that the large container doors can be opened and the rails laid out to pull Tiffy out of the container onto the launching rack on the working deck. The mission has already been saved on the computer in the AUV. At the same time, the ROV has finished its dive and is almost back on deck at the stern of the SONNE. So it’s time for Tiffy‘s dive no. 379 to commence.

Deutsche Version

Tauchgang Nr. 379

Marcel Rothenbeck, AUV-Team – GEOMAR Helmholtz-Zentrum für Ozeanforschung Kiel, Deutschland

Wir sind mittlerweile seit 40 Tagen auf See. Rings um das Schiff sehen wir erwartungsgemäß nur Wasser, soweit das Auge reicht, und ab und zu eine Gruppe Rotfußtölpel, die das Schiff umfliegen. Draußen an Deck ist es schwül. Das Wetter hätte sich dieser Tage laut Vorhersage verschlechtern sollen, zu schlecht für einen Tauchgang. Aber der Wetterbericht irrte sich dieses Mal.

Im Hangar und im vorderen Teil des Arbeitsdecks ist es eher ruhig. Zum einen, weil das ROV – verbunden mit dem Schiff über ein langes Kabel am Heck – am Meeresboden arbeitet. Zum anderen, weil viele der Wissenschaftler:innen, die mit dem Kastengreifer und dem Multicorer Sedimentproben sammeln, nach einer langen, arbeitsreichen Nacht noch schlafen. Als ich vom Hangar, wo der Bootsmann mit seinem Pausenkaffee sitzt, aufs Arbeitsdeck trete, höre ich eine Grille zirpen. Das tut sie schon seit dem Auslaufen aus Port Hueneme vor knapp sechs Wochen und jeder fragt sich, wovon sie hier lebt. Auf dem Weg zum Achterdeck passiere ich ein paar der Geräte, die in der Nacht zu Wasser gelassen wurden und schließlich zwei Container.

Die Tür des zweiten Containers ist mit Holz verschlossen, über dem Schlitz für die Zuluft der Klimaanlage hat irgendein Schelm ein Schild mit der Aufschrift „Keine heiße Asche einwerfen“ geklebt. Die originale Klimaanlage hatte vor einigen Tagen den Dienst verweigert. Als ich zur Tür des Containers auf der Seeseite gelange, muss ich kräftig an der Tür ziehen, denn die Ersatzklimaanlage, die sich wacker hält, erzeugt einen leichten Unterdruck im Container. Von drinnen kommt mir ein Schwall kühle Luft und laut schallend „Do they know its Christmas“ von Band Aid entgegen. Im Container sind drei Personen damit beschäftigt, ein Gerät für den nächsten Tauchgang vorzubereiten. Meine Stimme hat keine Chance gegen den Weihnachtsklassiker aus der Anlage über Annas Kopf. Sie lächelt und dreht die Musik leiser.

„Die Mission für Tiffy liegt auf dem Server“ sage ich. Anna nickt und geht dann weiter die Checkliste durch, die rechts neben ihr auf einem schmalen Tisch liegt. Vor ihr leuchtet ein Bildschirm, der Tiffys Daten anzeigt. Auch Karl hebt seinen Kopf und nickt. Er hält eine Leine, die von Torge sorgsam Törn für Törn in einem Metallbehälter in Tiffys Nase verstaut oder aufgeschossen wird, wie es in der Seemannssprache heißt.

Aber wer ist Tiffy überhaupt? Tiffy ist ein sogenanntes Autonomes Unterwasserfahrzeug (engl.: Autonomous Underwater Vehicle, kurz AUV). Ihr offizieller Name lautet AUV ABYSS, aber ihr Spitzname hat sich irgendwie gehalten. Sie hat die Form einer vier Meter langen Zigarre, wiegt fast 900 Kilogramm und kann bis zu 6.000 Meter tief tauchen. Außerdem ist sie knallgelb. Sie taucht bereits seit 14 Jahren durch die Tiefen der Ozeane, was ein stattliches Alter für ein Tiefsee-AUV ist. Heute Abend soll sie auf 4.500 Meter Tiefe abtauchen und fünf Meter über dem Grund einem vorgegebenen Kurs folgen. Bei diesem Abstand wird der Meeresboden durch das Blitzlicht von Tiffys Kamera optimal ausgeleuchtet.

Im Container läuft inzwischen der nächste Weihnachtshit. Links neben mir schaut Anna weiter auf den Bildschirm und checkt, ob Tiffys Sensoren richtig arbeiten und gute Werte liefern. Das Seitensicht-Sonar, mit dem Tiffy die Topographie des Meeresbodens erfasst, wurde schon getestet. Die Kamera ist zum Schluss dran. Es gibt eine Checkliste, die Schritt für Schritt durchgegangen wird.

„Die Mission laden wir ganz am Ende hoch, okay?“ fragt Anna ohne den Blick vom Bildschirm zu nehmen. Ich nicke. Die Mission ist sozusagen Tiffys Arbeitsprogramm während eines Tauchgangs. Sie enthält jeden Schritt, den Tiffy auf dem Weg von der Wasseroberfläche zum Meeresboden, am Meeresboden und wieder zurück an die Oberfläche durchführen muss. Die aktuelle Mission wird 19 Stunden dauern. Dabei soll das AUV insgesamt zirka 100 Kilometer zurücklegen. In der Mission wird genau festgelegt, wo ihr nächster Wegpunkt liegt, wie schnell sie „fliegen“ soll, welche Sensoren an- oder abgeschaltet werden sollen und wie lange sie Zeit hat, um den nächsten Wegpunkt zu erreichen. Braucht sie länger, wird der Tauchgang abgebrochen. Das Sicherheitsprogramm geht dann von einem Fehler aus und lässt Tiffy ein Notfallgewicht abwerfen. So wird sie leichter und steigt auf. Aber das sollte nur im Notfall passieren.

Bei allen Tauchgängen auf dieser Expedition kommen die Kamera und das Seitensicht-Sonar zum Einsatz. Tiffy soll in verschiedenen Gebieten so viele Fotos machen, dass wird daraus an Bord mit einer speziellen Software ein großes Foto-Mosaik erstellen können. Dieses ist für die Forschenden sehr viel nützlicher als die 50.000 Einzelfotos, die bei einem einzelnen Tauchgang entstehen. Während die Kamera jede Sekunde ein Foto schießt, scannt das Seitensichtsonar kontinuierlich einen 100 Meter breiten Streifen des Meeresbodens (je 50 Meter links und rechts des AUV). Auch diese Daten werden später zu einer Übersichtskarte verarbeitet.

Im Container auf dem Arbeitsdeck hat Torge den Tampen (Seil) bereits sauber in eine Box oben an Tiffys Nase gepackt und verbindet das Ende dieser Leine mit einem Block. Anschließend drückt er den Block in die dafür vorgesehene Öffnung über der Box, sodass er formschlüssig mit der Nase abschließt. Er streicht mit der Hand über den Block und nickt zufrieden. „Du kannst es jetzt auslösen, Anna“, sagt Torge. Nach wenigen Sekunden ist das Klacken der Verriegelung zu hören, die den schwimmfähigen Block freigibt. Check.

Der Block wird ausgelöst, wenn das AUV wieder aufgetaucht ist und in richtiger Entfernung vor dem Schiff liegt, bereit, um eingefangen zu werden. Aber dafür muss Tiffy erst einmal zur Oberfläche gelangen. Wenn beim Tauchgang alles reibungslos funktioniert und Tiffy den letzten Wegpunkt erreicht hat, erhält sie den Befehl zum Auftauchen. Dann zieht sie die Nase nach oben und fährt spiralförmig der Wasseroberfläche entgegen. Bei einer Tiefe von 4500 Metern dauert das Auftauchen rund 75 Minuten. Sobald Tiffy an der Wasserfläche angekommen ist, ermittelt sie mittels GPS ihre Position. Die Koordination schickt sie uns im Container, damit wir wissen, wo das Schiff zur Bergung hinfahren muss. Ist das Schiff nahe genug an Tiffy herangekommen, schicken wir ihr eine Nachricht, dass sie den Schwimmblock entriegeln soll. Dadurch wird der Tampen (Seil) frei, den die Deckscrew der FS SONNE dann mit einem Wurfhaken einfängt.

Im Container wurde die Checkliste bereits soweit abgearbeitet, dass die großen Containertüren geöffnet und die Schienen ausgelegt werden können, um Tiffy aus dem Container auf das Aussetzgestell auf dem Arbeitsdeck zu ziehen. Die Mission wurde bereits auf dem Computer im AUV gespeichert. Gleichzeitig hat das ROV seinen Tauchgang beendet und ist fast wieder an Deck am Heck der SONNE. Es kann also losgehen mit Tiffy und ihrem Tauchgang Nr. 379.