***deutsche Version siehe weiter unten***

Teaser: Scientists are concerned about surface active compounds (known as surfactants) in any air-sea exchange processes nowadays. During our ongoing research in the Baltic Sea, scientists from IOW and GEOMAR came together on RV EMB295 to address the question of how surfactants in surface seawater of the Baltic Sea control the rate at which carbon dioxide (CO2) and other climate active trace gases crosses the boundary between atmosphere and ocean.

In general, surfactants are special molecules that can facilitate binding of different chemical compounds that they do not naturally bind together. So, surfactants in the ocean can bind air and water molecules together, reduce surface tension and its vorticity and control gas transfer velocity (k) and air-sea exchange as the consequences.

In the oceans biological-derived surfactants in the form of soluble and non-soluble are produced via phytoplankton production, zooplankton grazing and bacterial degradation but they control exchange processes in the different way. While non-soluble surfactants form a monolayer physical barrier (like a blanket on the sea surface) and impedes molecular diffusion across the surface, soluble surfactants on the other hand, may exert greater control on air-sea exchange as they reform more quickly at the surface boundary after surface disruption by waves/winds.

Surfactants can also reduce the mixing in the boundary layer of the ocean by flattening the capillary waves caused by wind blowing across the surface. With less mixing, the very surface water becomes rich in CO2 and other trace gases and the rate at which the gas is absorbed by the Sea reduces.

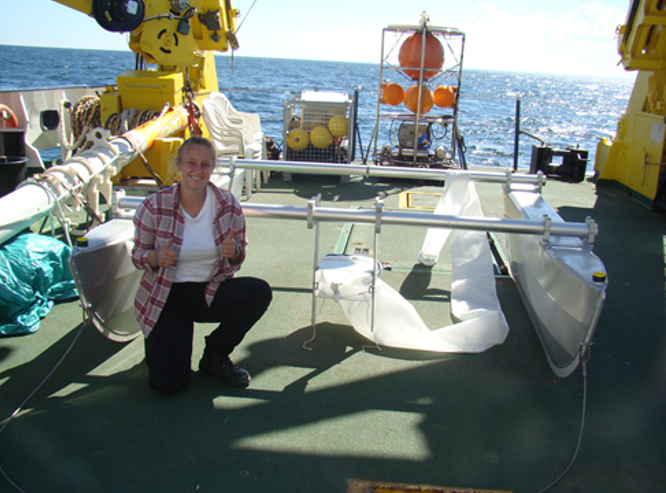

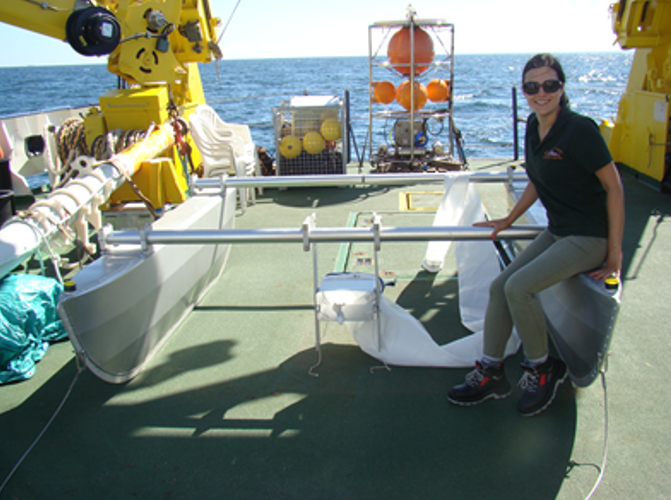

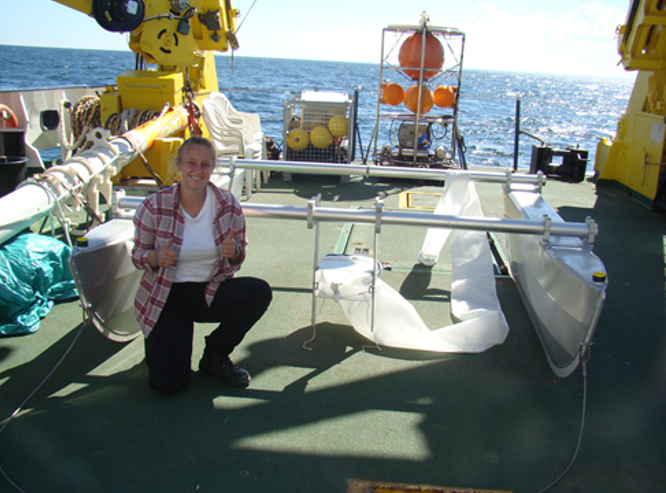

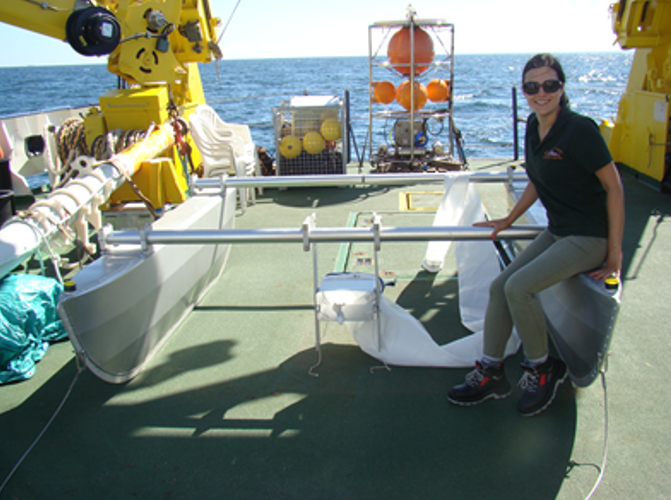

Josi and myself job on board EMB295 cruise is to investigate quantification, and biogenic characterization of the sea surface microlayer. To do that, twice per day at 6am and 6pm, we take samples of the very thin sea surface layer by deploying glass plate from the ship’s rubber boat (Figure 1) or Garrett screen from the bow of the mother ship (Figure 2). We also take samples from the reference water i.e. 1m depth using a Niskin bottle manually.

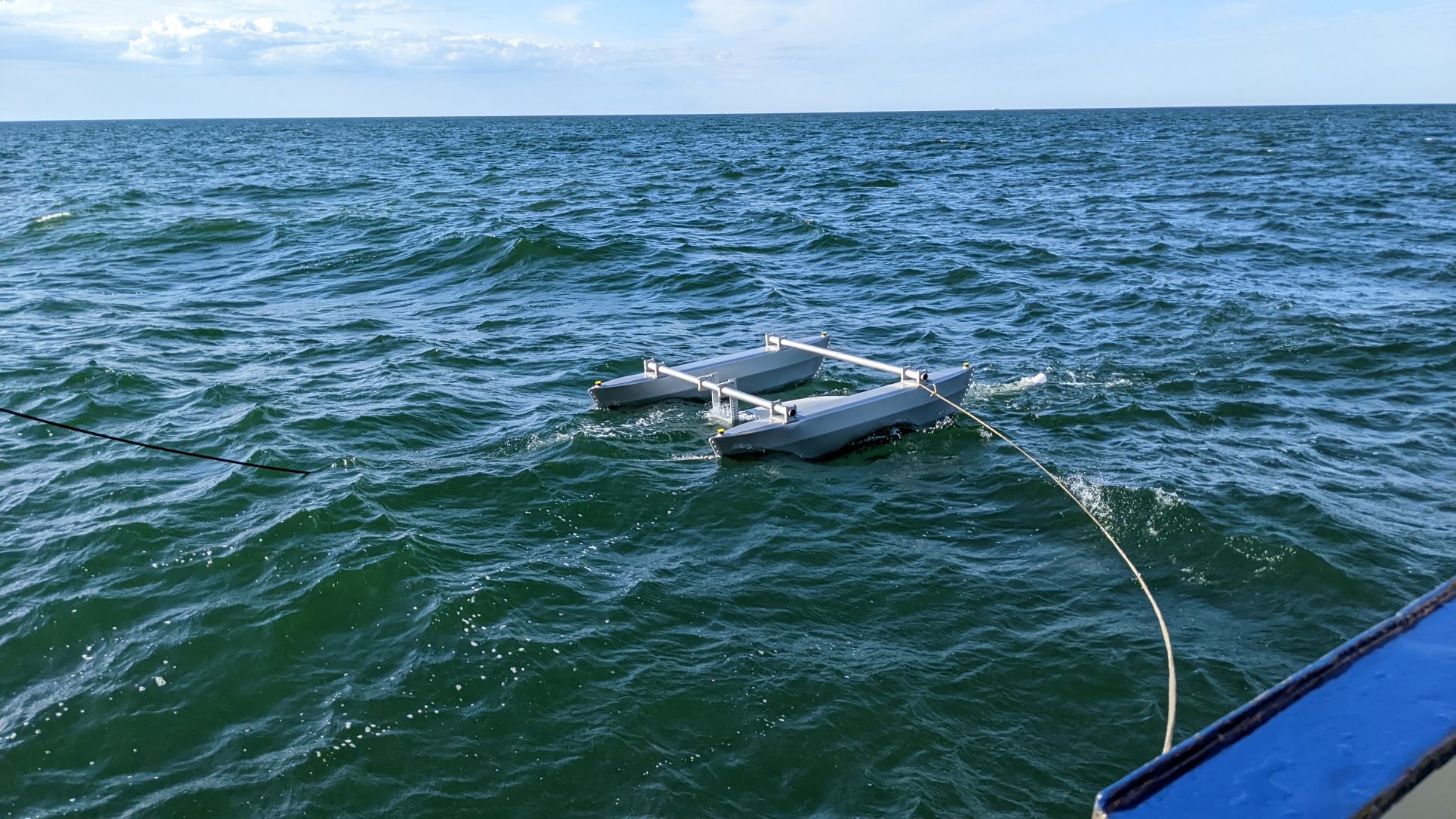

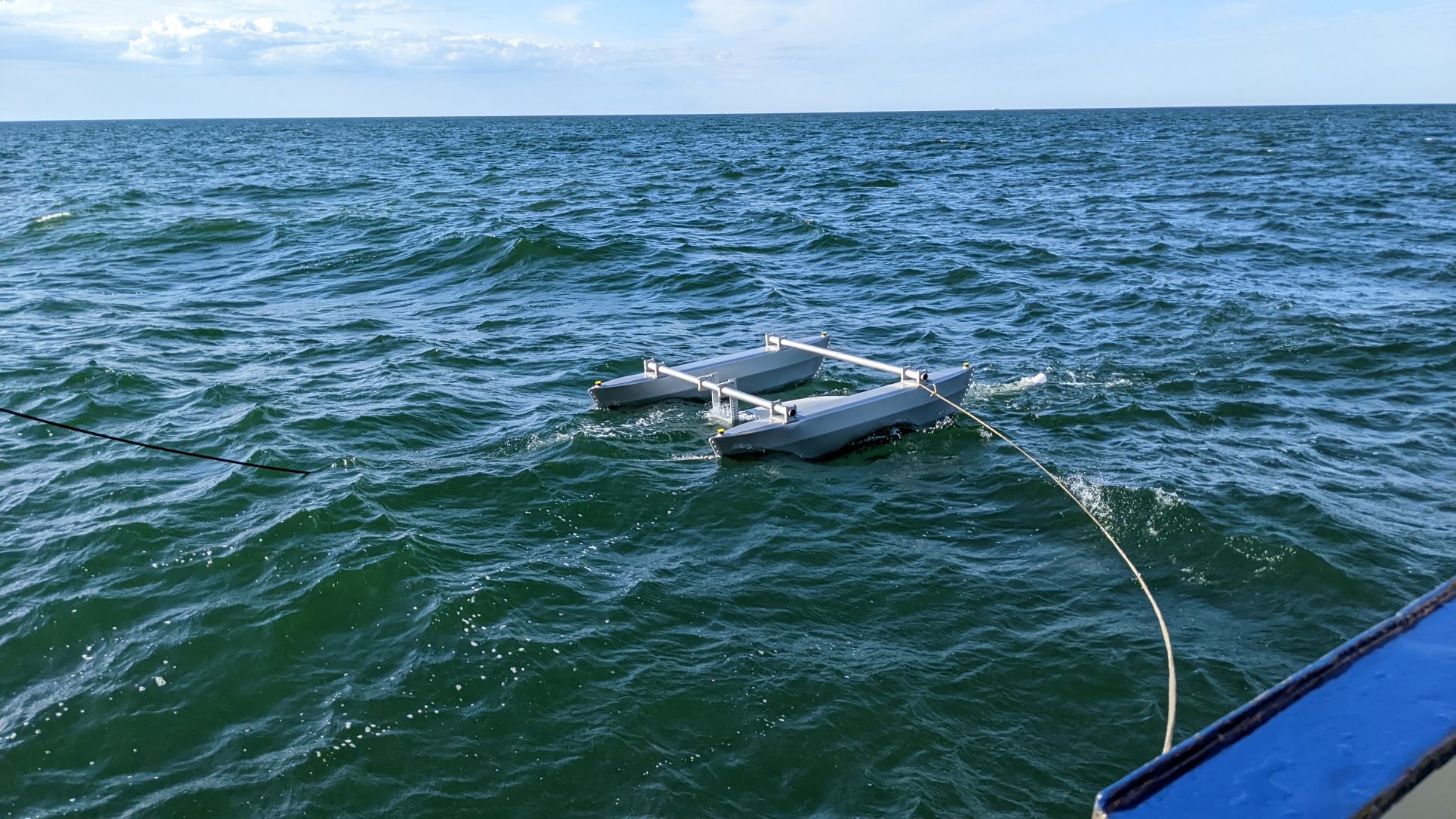

The catamaran and underlying net was also deployed at every designated stations to sample the sea surface and the reference depth (Figure 3).

So, our task is not a simple one. It is very hard to capture water from the very surface layer of the ocean when the surface is moving and you are standing on a ship/boat which is also moving. The ship itself is not free of surfactants and there is a risk of contaminating samples, so great care needs to be taken with the way water samples are captured and stored. We also monitor the sea surface during sampling like how wavy is the surface, any breaking waves that generate bubbles or any phytoplankton bloom (Figure 5).

All the collected samples will be analysed for several parameters including surfactant activity, colored and florescence dissolved organic matter (C/FDOM), nutrients, chlorophyll, total amino acids, total sugars, total organic carbon, gel particles (TEP and CSP), bacteria, phytoplankton, viruses and micro-phytoplankton.

We hope with combining our generated data with data from other research group on board, we can determine to what extent surfactants may control air-sea gas exchange in the Baltic Sea during productive months. As the cruise is about to an end and everyone is getting busy with packing, we will miss all those good and challenging days we had over the last three weeks and we hope to get together in a closed future to present some of the interesting results we managed to generate on this challenging expedition.

Text: Bita Sabbaghzadeh (IOW) and Josefine Karnatz (GEOMAR)

Deutsche Version:

Oberflächenaktive Substanzen! Sie sind überall!!!

Seit einiger Zeit beschäftigen sich Wissenschaftler mit den oberflächenaktiven Substanzen bei allen Austauschprozessen zwischen Luft und Meer. Im Rahmen unserer laufenden Forschungsarbeiten in der Ostsee haben sich Wissenschaftler des IOW und des GEOMAR auf FS EMB295 mit der Frage beschäftigt, wie oberflächenaktive Verbindungen in der Ostsee die Geschwindigkeit steuern, mit der Kohlendioxid (CO2) und andere klimaaktive Spurengase die Grenze zwischen Atmosphäre und Ozean überschreiten.

Bei oberflächenaktiven Substanzen handelt es sich im Allgemeinen um spezielle Moleküle, die die Bindung verschiedener chemischer Verbindungen erleichtern können, die von Natur aus nicht miteinander verbunden sind. So können oberflächenaktive Substanzen im Ozean Luft- und Wassermoleküle aneinanderbinden, die Oberflächenspannung und ihre Wirbelstärke verringern und als Folge davon die Gasübertragungsgeschwindigkeit (k) und den Luft-Meer-Austausch steuern.

In den Ozeanen werden biologisch hergestellte löslichen und unlöslichen oberflächenaktive Substanzen durch Phytoplanktonproduktion, Zooplanktonfraß und bakteriellen Abbau produziert, aber sie steuern Austauschprozesse auf unterschiedliche Weise. Während unlösliche oberflächenaktive Substanzen eine einschichtige physikalische Barriere (wie eine Decke auf der Meeresoberfläche) bilden und die Moleküldiffusion über die Oberfläche behindern, können lösliche oberflächenaktive Substanzen den Austausch zwischen Luft und Meer stärker beeinflussen, da sie sich nach einer Störung der Oberfläche durch Wellen/Wind schneller an der Grenzfläche neu bilden.

Oberflächenaktive Substanzen können auch die Durchmischung der Grenzschicht zwischen Atmosphäre und Meer verringern, indem sie die Kapillarwellen abflachen, die durch den Wind über die Oberfläche geblasen werden. Durch die geringere Durchmischung reichert sich im Oberflächenwasser CO2 und anderen Spurengasen, und die Geschwindigkeit, mit der das Gas vom Meer absorbiert wird, nimmt ab.

Josi und ich haben an Bord der EMB295 die Aufgabe, die Quantifizierung und biogene Charakterisierung der Mikroschicht der Meeresoberfläche zu untersuchen. Daher nahmen wir zweimal täglich um 6 Uhr morgens und um 18 Uhr abends Proben der sehr dünnen Meeresoberflächenschicht, indem wir die Wasseroberfläche mit Hilfe von Glasplatten vom Arbeitsboot beprobten (Abbildung 1) bzw. den Garrett-Screen vom Bug des Mutterschiffes einsetzen (Abbildung 2). Zudem nahmen wir Wasserproben mit einer manuellen Niskin-Flasche aus dem Referenzwasser aus 1 m Tiefe.

Mit Hilfe der Crew wurde zweimal täglich einen Katamaran (Abbildung 3) und ein ULW (underlying water) Netz (Abbildung 4) ausgesetzt, um Proben vom Oberflächenwasser und einer Referenztiefe von 1 m zu nehmen.

Unsere Aufgabe ist also nicht einfach. Es ist sehr schwierig, Wasser aus der obersten Schicht des Ozeans zu entnehmen, wenn die Oberfläche in Bewegung ist und man sich auf einem Schiff befindet, das sich ebenfalls bewegt. Das Schiff selbst ist nicht frei von oberflächenaktiven Substanzen, und es besteht die Gefahr, dass die Proben verunreinigt werden, so dass man bei der Entnahme und Lagerung der Wasserproben sauber und vorsichtig arbeiten muss.

Während der Probenahme beobachteten wir auch die Meeresoberfläche, z. B. wie wellig die Oberfläche ist, ob sich Wellen brechen, die Blasen erzeugen, oder das Vorhandensein von Phytoplanktonblüten (Abbildung 5)

Alle gesammelten Proben werden auf verschiedene Parameter hin analysiert, darunter Tensidaktivität, farbige und floreszierende gelöste organische Stoffe (C/FDOM), Nährstoffe, Chlorophyll, Gesamtaminosäuren, Gesamtzucker, gesamter organischer Kohlenstoff, Gelpartikel (TEP und CSP), Bakterien, Phytoplankton, Viren und Mikrophytoplankton.

Wir hoffen, mit unseren Daten und den Daten anderer Forschungsgruppen an Bord herauszufinden, inwieweit oberflächenaktive Substanzen den Gasaustausch zwischen Luft und Meer in der Ostsee während der produktiven Monate steuern können. Die Ausfahrt neigt sich nun dem Ende zu und alle sind mit packen beschäftigt. Wir werden die schönen und herausfordernden Tage an Bord, die wir in den letzten drei Wochen hatten, vermissen und wir hoffen, dass wir uns in naher Zukunft wieder treffen werden, um einige der interessanten Ergebnisse zu präsentieren, die wir auf dieser anspruchsvollen Expedition erzielen konnten.

Text: Bita Sabbaghzadeh (IOW) und Josefine Karnatz (GEOMAR)