Today, the sea is calm. We are still on our way south, some wind from behind, and a flat ocean ahead of us.

Wait, the sea surface is not flat!

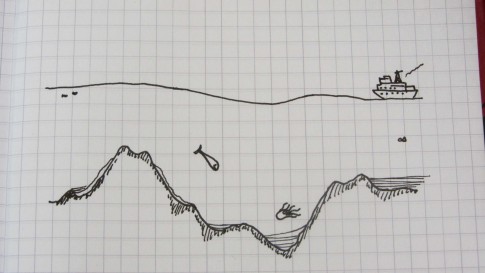

The scientists Sandwell and Smith discovered in the early 90’s that the ocean surface isn’t flat at all. Radar measurements from satellites (so-called satellite altimetry) revealed differences in sea surface height, even when tidal and wave effects were removed. They found that these elevation differences mimic the topography of the seafloor. That’s because large mountain chains have huge mass, and hence gravity, that attracts the water masses above. Valleys or trenches work the other way round, and their ‘negative gravity anomaly’ causes valleys on the sea surface.

Currently, advanced measurement technologies and fast computers allow modeling of seafloor topography for all the oceans (and also, thanks to climate change and reduced ice cover, for the Arctic Ocean) based on the sea surface height.

So, why are we in the middle of the Pacific mapping the ocean floor?

The oceans are on average 3000 to 5000m deep, so only large mountains have sufficient mass (and hence gravity) to keep a water column of 3-5km in place. The modeled seafloor topography achieves a horizontal resolution that only mountains or valleys of several kilometer in diameter will be seen, and this is only due to calibration with more detailed ship-based measurements. We are out here to map the ocean floor in a resolution of 50-100m, which is significantly better than the best gravity models can calculate.

And just a final side note: We know more about our (okay, ocean-less) neighbor planet. Mars is continuously mapped (and photographed) with a resolution of 10 to 20m.

—

Heute ist die See besonders ruhig. Wir sind immer noch auf dem Weg gen Süden, eine leichte Briese weht aus Nordost und vor uns liegt der flache Ozean.

Moment, die Meeresoberfläche ist nicht flach!

Schon Anfang der neunziger Jahre erkannten die Wissenschaftler Sandwell und Smith durch Radarmessungen von Satelliten (sogenannte Satelliten Altimetrie) aus, dass der Meeresspiegel auch nach Abzug von Gezeiteneffekten und Wellenbewegungen alles andere als glatt ist. Die Messungen zeigten, dass die Meeresoberfläche grob der Topographie des Meeresbodens folgt. Das erklärt sich dadurch, dass große Gebirgszüge durch ihre große Masse (und damit Schwere bzw. Schwerkraft) das Wasser um sie herum förmlich anziehen. Große Täler haben eine ‘negative Schwereanomalie’, bewirken also das genaue Gegenteil und zeichnen sich als Senken auf der Meeresoberfläche ab. Durch immer schnellere Computer, mehr Satelliten und genauere Vermessung des Meeresspiegels lässt sich mittlerweile die Topographie des Meeresbodens in allen Ozeanen modellieren (Dank Klimaerwärmung und schrumpfender Eisbedeckung auch im Arktischen Ozean).

Warum sind wir dann mitten im Pazifik zum Kartieren unterwegs?

Unsere Ozeane haben durchschnittliche Wassertiefen von 3000 bis 5000m; das bedeutet, die Gebirgszüge oder Täler am Meeresgrund müssen eine gewisse Größe (und damit Schwere) haben, um diese 3-5km an Wassersäule „in Position“ zu halten. Die heutigen Topographiemodelle des Meeresbodens haben eine Auflösung mit der Berge und Täler mit mehreren Kilometern durchmesser erfasst werden können, allerdings nur, weil die Berechnungen detaillierte und genauere Schiffskartierungen berücksichtigen. Denn eine Kartierung vom Schiff erreicht im Schnitt eine Auflösung von 50 bis 100m, also deutlich besser als jedes noch so genaue satellitengestütze Modell.

Kurze Randbemerkung zum Schluss: Wir wissen mehr über die Oberflöche unserers (zugegeben ozeanfreien) Nachbarplaneten. Mars ist flächendeckend, mit einer Genauigkeit von 10-20m kartiert (und fotografiert).

Out of scale scetch to give an idea of the variety of features at the bottom of the oceans, and how they affect sea surface height. / Kleine (maßstabsungetreue) Skizze, um zu verdeutlichen, wie wenig die vielfältige Topographie am Meeresboden die Höhe der Meeresoberfläche letztlich beeinflusst.

Hallo Meike,

interessanter Einstieg ins Thema. Und schön, etwas von Dir zu lesen. Im Moment ist im Pazifik ja eine Menge los.

Beste Grüße von der SONNE (auf 20° 40,4’S 070° 48,5′ W)

Jan

Hi Meike and Sebastian!

All the best from those staying at home in stormy and rainy Kiel! Enjoy your trip!