Dear interested reader, colleagues, friends and families,

the marine food web is complex and the techniques to explore its properties can be very challenging. The central players in the food web are plankton – Ancient Greek for “wandering” – which are the aquatic organisms that inhabit the pelagial of the ocean. They are extremely diverse including viruses, bacteria, protists, plants or animals. We are mainly interested in the activity of microbes in the deep sea: How much do bacteria eat, and how much do protists? And more important for us: how can we investigate it?

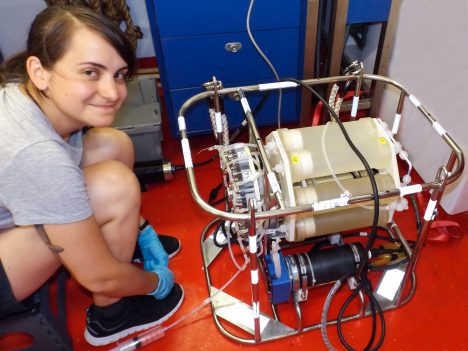

The biologists from Vienna of the M139 team came up with a fancy electronic machine, that is the “in-situ microbial incubator” (ISMI) (Image 1). The ISMI can do experiments in the deep sea while being exposed to all its extreme conditions like low temperature and high pressure. It was thought that high pressure has an influence on the productivity of bacteria. To test this, the Vienna group provided radioactively labelled amino acids (3H-Leucine) for deep-sea bacteria in bottles. Once the ISMI arrived in 4000 m depth, a pump floated the bottles with deep-sea water and bacteria living there could start to take up the nutritious substrate. After a few hours, a little computer activated another pump to direct the water into the next bottle containing a special reagent fixing all bacteria (freezing in all biological structures). Then the ISMI started its ascent to the surface and the biologists measured the 3H-Leucine that was taken up by the cells. The results show a clear difference between 3H-Leucine uptake in the deep sea by bacteria compared to incubation tests at surface, therefore a low productivity of deep-sea bacteria (Image 2-5).

Research benefits from international collaborations (Image 6) and, this time, the Cologne group was excited to use the ISMI for another project. To study the feeding activity of protists, bottles were prepared with different fluorescent particles in the size of viruses or bacteria and sent down to the deep sea. After the ISMI had done its job, they made images of the fixed cells. By counting the fluorescent particles inside the cells it was estimated how active the protists have been. They really found protists which had taken up fluorescent particles. This offers a new method to study activity of protists in situ in the deep sea.

You may imagine that there will always appear some problems when controlling a machine that is 4 km away in the depth. “The ISMI isn’t easy”, says Dr. Chie Amano. But all participating scientists from Vienna and Cologne are optimistic: It is really the first time that those experiments have been done directly in the deep sea and we are very excited about the expected results. They will tell us more about the interactions of viruses, bacteria and protists in the microbial food web of the deep ocean.

Your M139 team

–

Liebe interessierte Leser, Kollegen, Freunde und liebe Familien,

das marine Nahrungsgewebe ist ein so komplexes System, dass die Techniken seiner Untersuchung eine große Herausforderung darstellen können. Das Plankton – altgriechisch für „ das Umherschwebende“- spielt die Schlüsselrolle unter den aquatischen Meeresbewohnern des Freiwassers. Es ist eine extrem diverse Gruppe, zu der Viren, Bakterien, Einzeller, Pflanzen und Tiere gehören. Wir sind hauptsächlich an der Aktivität von Mikroben in der Tiefsee interessiert: Was konsumieren Bakterien, und wieviel fressen die Einzeller? Und wichtiger für uns: Wie können wir deren Aktivität in der Tiefe untersuchen?

Die Biologen des M139 Teams aus Wien haben eine spektakuläre elektronische Maschine mitgebracht, den “in-situ microbial incubator” (ISMI, „mikrobiellen in-situ Inkubator“) (Bild 1). Mittels des ISMI können Experimente mit den natürlichen, extremen Bedingungen, die in der Tiefsee herrschen, wie niedrige Temperaturen und hoher Druck, vor Ort in der Tiefe durchgeführt werden. Generell wird angenommen, dass hoher Druck einen Einfluss auf die Produktivität von Bakterien hat. Um dies zu testen, versieht die Gruppe aus Wien Flaschen mit radioaktiv markierten Aminosäuren (3H-Leucin) als Nahrung für die Tiefseebakterien.

Sobald der ISMI in 4000m Tiefe ankommt, werden die Flaschen mit Tiefseewasser vollgepumpt und die in diesem Wasser lebenden Bakterien können mit der Aufnahme des Nahrungssubstrates beginnen. Nach ein paar Stunden aktiviert ein kleiner Computer eine weitere Pumpe, um das Wasser zur nächsten Flasche zu leiten, in der ein spezielles Reagens alle Bakterien fixiert (sozusagen alle biologischen Strukturen konserviert).

Daraufhin beginnt der ISMI seinen Weg zurück an die Oberfläche und die Biologen messen die 3H-Leucin-Aufnahme durch die Zellen. Die Ergebnisse zeigen deutliche Unterschiede zwischen der 3H-Leucin-Aufnahme der Bakterien in der Tiefsee und Inkubationstests an der Oberfläche, demnach also eine geringe Produktivität der Tiefseebakterien (Bild 2-5).

Forschung wird durch internationale Zusammenarbeiten bereichert (Bild 6), in unserem Fall dadurch, dass die Kölner Gruppe sehr daran interessiert ist, den ISMI für ein anderes Projekt nutzen zu können. Um die Fraßaktivität von Einzellern zu untersuchen, wurden die Flaschen mit fluoreszierenden Partikeln in der Größe von Viren und Bakterien (Bild 1) versehen und in die Tiefsee geschickt. Nachdem der ISMI seine Arbeit verrichtet hat, analysieren die Kölner die fixierten Zellen unter dem Mikroskop. Indem die Anzahl der fluoreszierenden Partikel pro Zelle gezählt wird, kann die Aktivität der Einzeller abgeschätzt werden. Die Biologen aus Köln haben tatsächlich Einzeller gefunden, die fluoreszierende Partikel aufgenommen haben. Dies stellt eine neue Methode dar, um die Aktivität von Einzellern in der Tiefsee untersuchen zu können.

Sie können sich sicherlich vorstellen, dass es nicht unproblematisch ist, eine Maschine zu steuern, die sich 4 km weit weg in der Tiefe befindet. „Der ISMI ist nicht einfach”, sagt Dr. Chie Amano. Aber alle beteiligten Forscher aus Wien und Köln sind optimistisch: Es ist wirklich das erste Mal, dass solche Experimente direkt in der Tiefsee durchgeführt werden konnten und wir sind sehr gespannt auf die noch folgenden Ergebnisse. Sie werden uns mehr über die Interaktionen zwischen Viren, Bakterien und Einzellern innerhalb des mikrobiellen Nahrungsgewebes der Tiefsee verraten.

Ihr M139-Team

Image 1 | The ISMI with all its tubes and wires before. (Photo: Hartmut Arndt)

Image 2 | The ISMI is heading down to 4000 m depth. (Photo: Johannes Werner)

Image 3 | Dr. Chie Amano from Vienna is happy that the ISMI came back to the surface. (Photo: Johannes Werner)

Image 4 | Working with the ISMI on board the RV Meteor. (Photo: Johannes Werner)

Image 5 | Water samples are retrieved from the fixation bottles after the ISMI deployment. (Photo: Johannes Werner)

Image 6 | The ISMI team, a collaboration between Vienna and Cologne. (Photo: Johannes Werner)