On Åland, the seasons change quickly and vividly. In summer, the nights never really grow dark as the sun hovers just below the horizon. Only a few months later, autumn creeps in and softly cloaks the island in darkness again. The rhythm of the seasons is mirrored by the biological station itself; researchers, professors, and students arrive and depart, bringing with them microscopes, incubators, mesocosms, and field gear to study the local flora and fauna peaking in the mid of summer.

This year’s GAME project is the final chapter of a series of studies on light pollution. Together, we, Pauline & Linus, are studying the effects of artificial light at night (ALAN) on epiphytic filamentous algae. Like the GAME site in Japan, Akkeshi, the biological station Husö here on Åland experiences very little light pollution, making it an ideal place to investigate this subject.

We started our journey at the end of April 2025, just as the islands were waking up from winter. The trees were still bare, the mornings frosty, and the streets quiet. Pauline, a Marine Biology Master’s student from the University of Algarve in Portugal, arrived first and was welcomed by Tony Cederberg, the station manager. Spending the first night alone on the station was unique before the bustle of the project began.

Linus, a Marine Biology Master’s student at Åbo Akademi University in Finland, joined the next day. Husö is the university’s field station and therefore Linus has been here for courses already. However, he was excited to spend a longer stretch at the station and to make the place feel like a second home.

Our first days were spent digging through cupboards and sheds, reusing old materials and tools from previous years, and preparing the frames used by GAME 2023. We chose Hamnsundet as our experimental site, (i.e. the same site that was used for GAME 2023), which is located at the northeast of Åland on the outer archipelago roughly 40 km from Husö. We got permission to deploy the experiments by the local coast guard station, which was perfect. The location is sheltered from strong winds, has electricity access, can be reached by car, and provides the salinity conditions needed for our macroalga, Fucus vesiculosus, to survive.

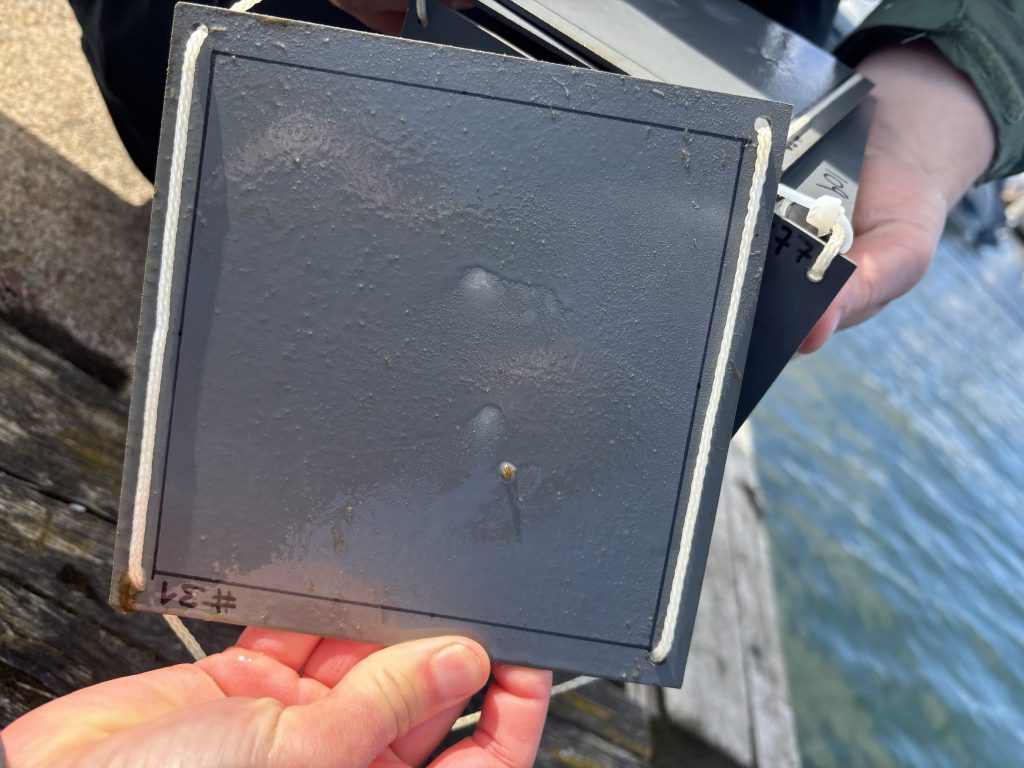

To assess the conditions at the experimental site, we deployed a first set of settlement panels in late April. At first, colonization was slow; only a faint biofilm appeared within two weeks. With the water temperature being still around 7 °C, we decided to give nature more time. Meanwhile, we collected Fucus individuals and practiced the cleaning and the standardizing of the algal thalli for the experiment. Scraping epiphytes off each thallus piece was fiddly, and agreeing on one method was crucial to make sure our results would be comparable to those of other GAME teams.

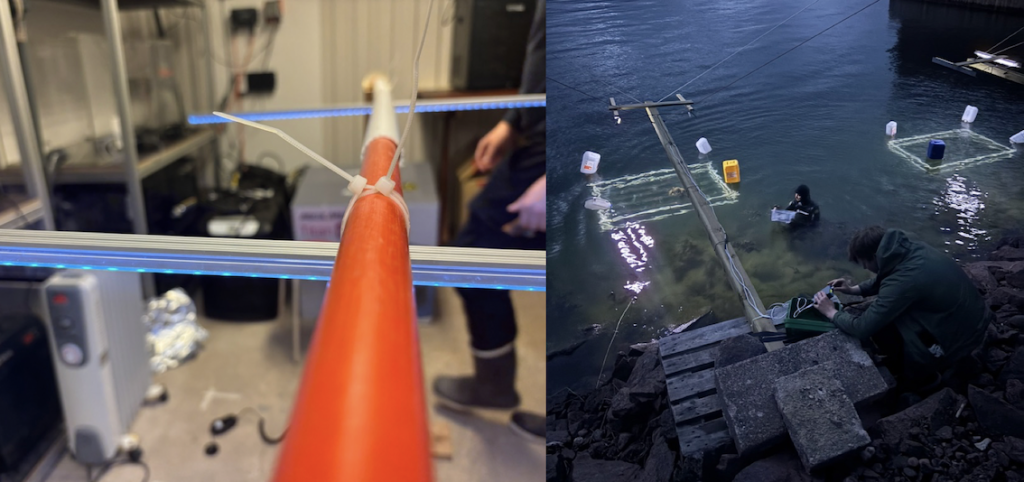

By early May, building the light setup was a project in itself. Sawing, drilling, testing LEDs, and learning how to secure a 5-meter wooden beam over the water. Our first version bent and twisted until the light pointed sideways instead of straight down onto the algae. Only after buying thicker beams and rebuilding the structure, we finally got a stable and functional setup that could withstand heavy rain and wind. The day we deployed our first experiment at Hamnsundet was cold and rainy but also very rewarding!

Outside of work, we made the most of the island life. We explored Åland by bike, kayak, rowboat, and hiking, visited Ramsholmen National Park during the ramson/ wild garlic bloom, and hiked in Geta with its impressive rock formations and went out boating and fishing in the archipelago. At the station on Husö, cooking became a social event: baking sourdough bread, turning rhubarb from the garden into pies, grilling and making all kind of mushroom dishes. These breaks, in the kitchen and in nature, helped us recharge for the long lab sessions to come.

Every two weeks, it was time to collect and process samples. Snorkeling to the frames, cutting the Fucus and the PVC plates from the lines, and transferring each piece into a freezer bag became our routine. Sampling one experiment took us 4 days and processing all the replicates in the lab easily filled an entire week. The filtering and scraping process was even more time-consuming than we had imagined. It turned out that epiphyte soup is quite thick and clogs filters fastly. This was frustrating at times, since it slowed us down massively.

Over the months, the general community in the water changed drastically. In June, water was still at 10 °C, Fucus carried only a thin layer of diatoms and some very persistent and hard too scrape brown algae (Elachista). In July, everything suddenly exploded: green algae, brown algae, diatoms, cyanobacteria, and tiny zooplankton clogged our filters. With a doubled filtering setup and 6 filtering units, we hoped to compensate for the additional growth.

However, what we had planned as “moderate lab days” turned into marathon sessions. In August, at nearly 20 °C, the Fucus was looking surprisingly clean, but on the PVC a clear winner had emerged. The panels were overrun with the green alga Ulva and looked like the lawn at an abandoned house. Here it was not enough to simply filter the solution, but bigger pieces had to be dried separately. In September, we concluded the last experiment with the help of Sarah from the Cape Verde team, as it was not possible for her to continue on São Vicente, the Cape Verdean island that was most affected by a tropical storm. Our final experiment brought yet another change into community now dominated by brown algae and diatoms. Thankfully our new recruit, sunny autumn weather, and mushroom picking on the side made the last push enjoyable.

By the end of summer, we had accomplished four full experiments. The days were sometimes exhausting but also incredibly rewarding. We learned not only about the ecological effects of artificial light at night, but also about the very practical side of marine research; planning, troubleshooting, and the patience it takes when filtering a few samples can occupy half a day.