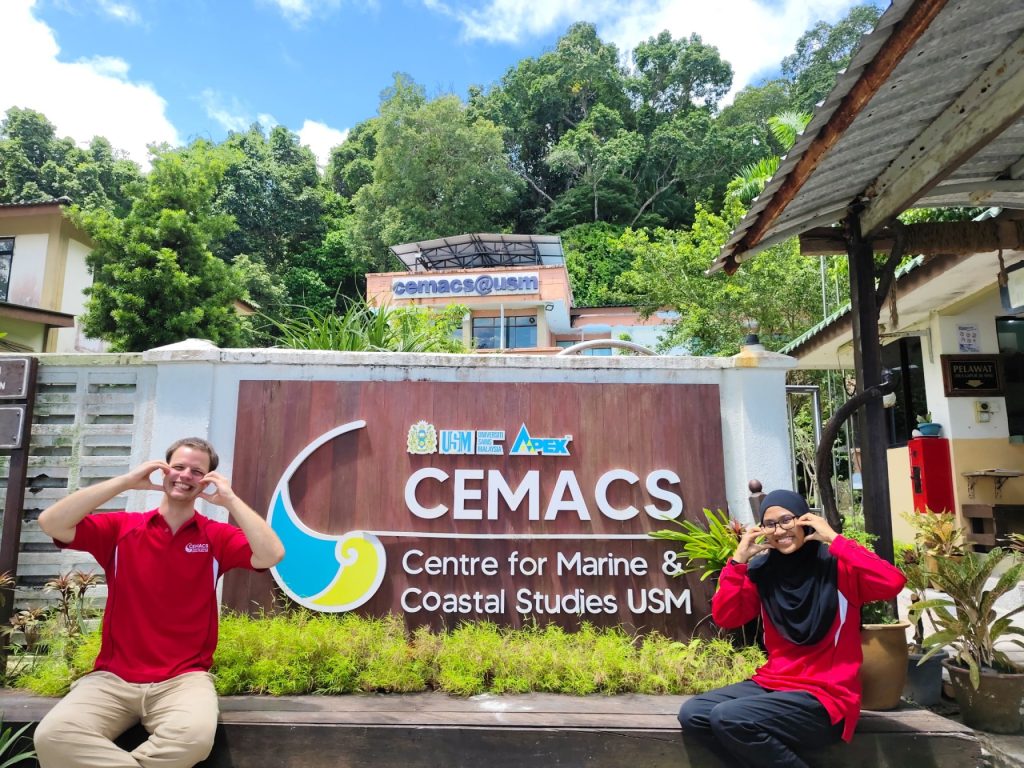

It’s an early morning in the northern part of Penang Island, Malaysia. The sun is slowly rising over the horizon, casting golden reflections on the still calm sea as our boat hums towards the research station. The wind grazes our faces and the air is filled by the splashes of the salty sea. The green jungle is slowly coming to life with water dripping down the trees, chirping birds and macaques dancing in the canopy. This is our daily commute to the secluded marine station. Established in August 1991, the Centre of Marine and Coastal Studies (CEMACS) is located in Teluk Aling, the northwest coast of Penang Island in the Penang National Park. As Tom is living somewhere near the city center in Georgetown, he travels to the national park everyday by bus for only 3 Malysian Ringgit (around 0.60€) per ride. Even though getting up early in the morning is annoying, the 45 minutes-ride will serve you with an unexplained scenery while driving down the crooked road. In contrast to this, Farhanah only needs to walk for 5 minutes to the entrance of the national park as she lives nearby. After reaching the entrance of the National Park you have two options to get to the marine station, either by a 1 hour-hike through the forest or by a 5 minutes boat travel from the jetty at the national park.

Malaysia is a fascinating country, geographically split into Peninsular Malaysia and East Malaysia, which occupies the northern part of the island of Borneo. Both parts are characterized by dense tropical rainforests. Malaysia’s topography is diverse, featuring coastal plains that rise to hills and rugged mountains inland. The coastline is either shaped by mangrove mudflats or is dominated by big boulders. This the case on the westside of peninsular Malaysia, whereas Borneo and the east of peninsular Malaysia are mainly rocky shores of different rock types.

Our hosting institute, CEMACS and also our field site are located on the island of Penang. Presently, research and training are conducted at CEMACS and both are focused on biodiversity and conservation of marine ecosystems, coastal forest ecosystems, mariculture and marine mammal ecology. In addition, CEMACS is one of the active marine stations in Malaysia that always contributes to various outreach programs, which also connect the institute to the local population. This is not only important for the marine research that is done at CEMACS but has mutual benefits for both parties. The institute is particularly successful in terms of education. CEMACS always opens golden opportunities for students who are looking for internships or those who want to pursue their studies in postgraduate programmes. More specifically, CEMACS is situated within a national park, far away from the noise and the light of civilization. The remoteness of this location makes it an ideal spot for studying light pollution, which is the focus of our master’s theses within the GAME project.

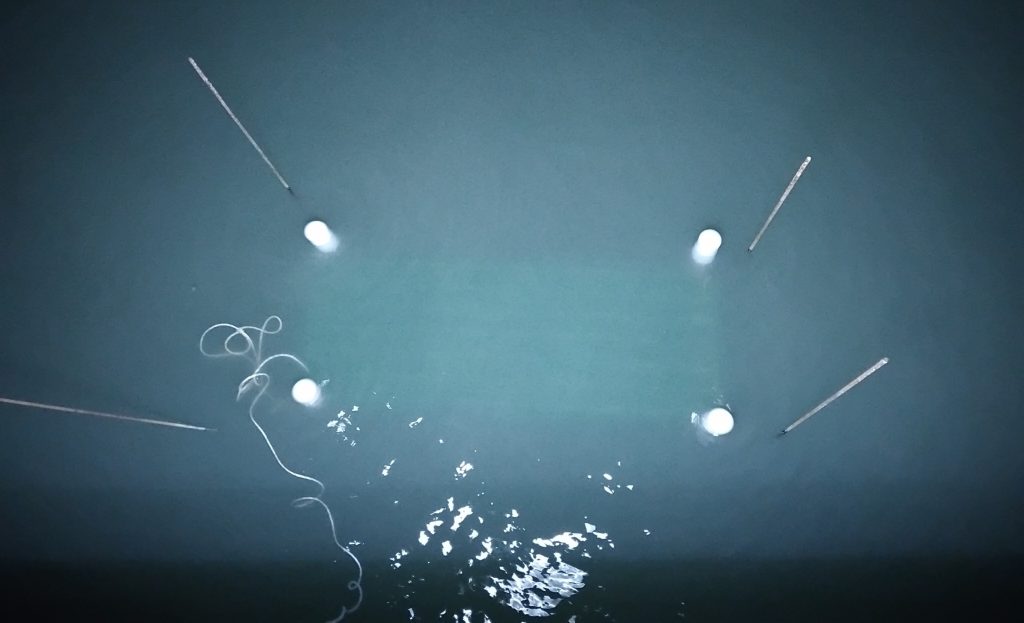

We are Tom and Farhanah, two marine biology students currently immersed in a field experiment investigating how artificial light at night influences marine epiphytic communities. For this, we deploy large metal frames, which are attached to buoys and groundweights, in the shallow sea near the jetty of CEMACS. Each frame represents one night-time light treatment level and is equipped with macroalgae and with PVC panels, which both serve as substrates for various marine photoautotrophic organisms, such as diatoms and epiphytic macroalgae, which settle and grow under the different light regimes. Between us two experimenters there is a difference in the nighttime light intensity: Farhanah investigates the effects of light in an intensity range of 20-30 lux, while Tom covers a range of 30-40 lux. These light levels are realized by LED strips that are attached to the outer part of the jetty. They shine down on the frames and the light is directed by self-made aluminium reflectors. In our first experiment, we retrieved the macroalgae substrates after 4 nights, while the PVC panels were retrieved after 8 nights. This difference is due to the fact that the two substrates were colonized at different speeds. Furthermore, we intended to keep the number of barnacles on the substrates, especially on the PVC panels, low. Hence, we needed to stop the experiments early. From all substrates we obtain the dry weight of the epiphytic biomass and the chlorophyll a concentration.

Photo: Cheow Mei

The general concept of the experiment that we are doing sounds simple enough on paper, but nature has a way of keeping things interesting. For instance, the ribbon jellyfish is a frequent visitor to our study site. Usually, they are drifting with the currents and are wandering around the metal frames near to the jetty, especially when it is low tide and the water is calm. Their tentacles are often stuck on the net that we put around the frame to minimize the influence of the herbivorous fish. These elegant yet formidable creatures can deliver a painful sting, which means that snorkelling near the experimental set-up is a hazardous endeavour. To make things even trickier, the underwater visibility is often poor. On some days, we can barely see our hands in front of us, which adds an extra layer of challenge to monitoring and documentation. One team member always needs to keep her/his eyes open and look out for danger and alert the other team member in the water if a jellyfish is nearby.

Despite the physical demands that come with implementing and maintaining our experiment, living and working in Malaysia has been an incredibly enriching experience for us, with the opportunities of organizing most of the project on our own while being in a constant cultural exchange. The climate is hot and humid, and the tropics come with their own unique rhythm. For someone used to northern climates, such as Tom, the constant warmth can be draining, but it also makes the occasional breeze feel like a gift. One thing that fascinates us is how little seasonal variations exist here due to Malaysia’s location just 5° north of the equator. Unlike the dramatic seasonal changes in light availability and temperature that occur in northern Europe, such as at the GAME site in Finland, here the day length remains fairly constant year-round. This makes Malaysia an interesting place for studying the effects of light pollution and this will become particularly relevant when we will compare our findings globally in the last phase of the project.

Our daily routines revolve around careful underwater monitoring, algae collection in the field, and lab work. Yet, our time in Malaysia is about more than just science. It’s also about cultural exchange and personal growth. Malaysia is truly multicultural, with Malay, Chinese, Indian, and indigenous cultures coexisting harmoniously. English is widely spoken, making it easy to communicate and connect with locals. Still, the primary language is Malay, and I (Tom) have started to learn it with the help of Farhanah. She patiently teaches me a few words each day, and in return, I help her practice German.

Sometimes, instead of taking the boat, we choose the jungle route through the national park to the station. It’s a one-hour hike through lush rainforest teeming with wildlife – monkeys, birds, and occasional monitor lizards (so far no snakes). It’s humid, yes, and sometimes slippery, but the sights and sounds are like nothing else. It reminds us daily how closely our work is tied to nature and how important it is to understand and protect it.

Hiking in Penang is an unforgettable experience, offering a deep dive into Malaysia’s tropical landscapes. The Penang Hills are covered with dense, emerald-green forest, crisscrossed by trails that lead to cascading waterfalls, serene viewpoints, and hidden jungle streams. Along the way, we often encounter curious macaques swinging through the trees, monitor lizards basking in the sun, and a chorus of birds and insects that soundtrack every step. The jungle is truly alive here, densely packed with all kinds of organisms, making every hike feel like a mini expedition. Beyond Penang, Malaysia boasts countless other hiking gems—from the misty trails of the Cameron Highlands to the more demanding ascents in Sabah and Sarawak on Borneo. No matter where you go, hiking in Malaysia is a chance to escape into nature, explore its rich biodiversity, and be reminded of how much beauty lies just beyond the beaten path.

Another highlight of Malaysia is the incredible variety of local food, reflecting the rich blend of Malay, Indian, and Chinese cultures. Whether it’s a plate of nasi lemak (rice cooked in coconut milk, egg, and anchovies), nasi goreng (fried rice), or mee goreng (fried noodles), Malay cuisine offers bold flavours that are both “comforting” and satisfying. Indian influences bring delights like roti canai—a flaky, buttery flatbread served with curry—and tosai, a thin, crispy fermented crepe made from rice and lentil batter, which is often eaten for breakfast. Chinese dishes such as cheow chung fun (Rice paper crepes filled with eggs, meats), noodle soups, and various dim sum (dumplings) items add to the diversity, often found sizzling in hawker stalls across the island. And no mention of Penang’s food scene would be complete without its tropical fruits: from the polarizing durian—known as the “king of fruits” with its intense aroma and creamy texture—to the sweet, juicy mangosteen, mango, banana, and coconut. The fresh products are always just around the corner, adding a perfect end to any spicy meal.

All in all, our time in Malaysia with the GAME project is more than just research. It’s an adventure packed with challenges, discoveries, and moments of awe. Whether it’s learning a new language, braving jellyfish, or conducting experiments in murky waters, we’re gaining skills, insights, and stories that will shape us for years to come. And in between all that, we’re also learning how to slow down, observe, and appreciate the complex beauty of marine ecosystems in the tropics.