Welcome to Chile! Muchos saludos desde Chile! Team Chile greets you from the southern hemisphere. Let us introduce ourselves: We are Lou & Bianca and we want to talk a bit about how the only southern hemisphere team in GAME 2025 is experiencing autumn and winter in Chile – instead of spring and summer like all the other teams.

Chile is a narrow strip of land between the Andes mountain range and the Pacific Ocean in South America. It is the beautiful country of black and white beaches along the cold and strong Humboldt Current. More than this, it is the country of completos (a kind of Chilean hotdogs) and empanadas, sea lions and pelicans, huge mountains and impressive coast lines.

Bianca’s origin is La Serena, a coastal city in north-central Chile, and since she was little she has been in contact with the sea. Bianca studied Marine Biology at the Universidad Católica del Norte in Coquimbo and is the local partner of Team Chile 2025. For her, being part of GAME is much more than an experiment. The GAME project is a challenge, but one of those exciting challenges that arise. “I’m grateful for the opportunity to collaborate and design an experiment together with my project mates, each of which is repeating it in their own corner of the sea with the goal of answering the same question in different oceans”.

Lou comes from Germany (Rheinland-Pfalz), studied Life Science Engineering as a bachelor program in Berlin and Molecular Biology and Evolution in Kiel for her master’s. Inspired by GEOMAR, she discovered in Kiel her interest in marine biology and got the chance to take part in GAME 2025. With this project, a dream became true: Having her own research project where she cannot just study marine biology, but also the Chilean culture and language. In her free time, she likes to hike in the national parks in the area and enjoys the music connection of Concepción (The city of rock in Chile – but there is also folklore, jazz, classic, …).

In April, during the boreal spring, we left Europe to enter the autumn in Chile. Due to its immense coast line, Chile is a preferable site to study marine biology. In the south, in Patagonia, the coast experiences really low temperatures due to Antarctic currents and is characterised by glaciers. The more you move to the north, the warmer it gets – even though the Humboldt Current makes sure that the water keeps a fresh temperature. This and the upwelling of cold and nutrient-rich deep water results in a high productivity and biodiversity along the coastline. With the availability of fish comes the fishing industry and the aquaculture of seafood and algae, which is one of the biggest sectors of the Chilean economy.

Our local supervisor is Dr. Ivan Hinojosa from the Catholic University of the Holy Concepcion (UCSC), he is a marine ecologist who is most of the time investigating an aspect of marine life that is not related to light pollution: His main interest is hydroacoustics – thus listening to everything that produces sounds in the ocean. This reaches from really small fishes to dolphins up to the famous songs of the ballenas, what, in Spanish, means whales. With his experience of diving, investigating and researching in the sea he already offered many GAME teams the opportunity to come to Concepción.

Now it is our turn to realize another GAME research project in Chile. This year, we want to look into the impact of artificial light at night (ALAN) on the epiphytes that grow on macroalgae. As everywhere in the world, also in Chile light pollution increases. Studies estimated that more than 22% of the world’s coastlines are already affected by artificial lighting from cities, ports, fishing boats, and tourist infrastructure, and this share continues to grow. As coastal development continues and LED technologies spread, light pollution is reaching further than ever before into the sea. The best example for this, which we experienced ourselves, was when we visited our study site in Talcahuano for the first time (read below more about this).

ALAN can disrupt circadian rhythms, reproductive cycles, foraging behaviour, larval settlement, and even predator-prey interactions. In marine environments, the effects of ALAN are still poorly understood compared to terrestrial ecosystems, but there is growing evidence that also underwater it can act as an insidious form of pollution. However, the scientific community is only just beginning to understand the ecological implications of this phenomenon. With our experiment, we want to draw attention to the fact that light pollution is not only a problem affecting the sky and the land, but also has effects below the sea surface.

Macroalgae are the backbone of coastal marine ecosystems in many regions worldwide, providing habitat, shelter, and food for numerous invertebrates and fish. Epiphytes are either microscopic unicelluar algae or small filamentous macroalgae that grow on the surfaces of large, long-living macroalgae (and seagrasses). On the one hand, they create microhabitats on the host surface, but, on the other hand, also impair the light, nutrient and gas supply for their hosts. By focusing on epiphytes growing on macroalgae, we explore a foundational level of coastal ecosystems. Here, already small shifts in different aspects of the epiphyte community may lead to big cascading consequences effecting the whole ecosystem. Thus, if ALAN changes epiphyte growth or biomass, it may indirectly affect those benthic ecosystems that depend on macroalgae for their functioning.

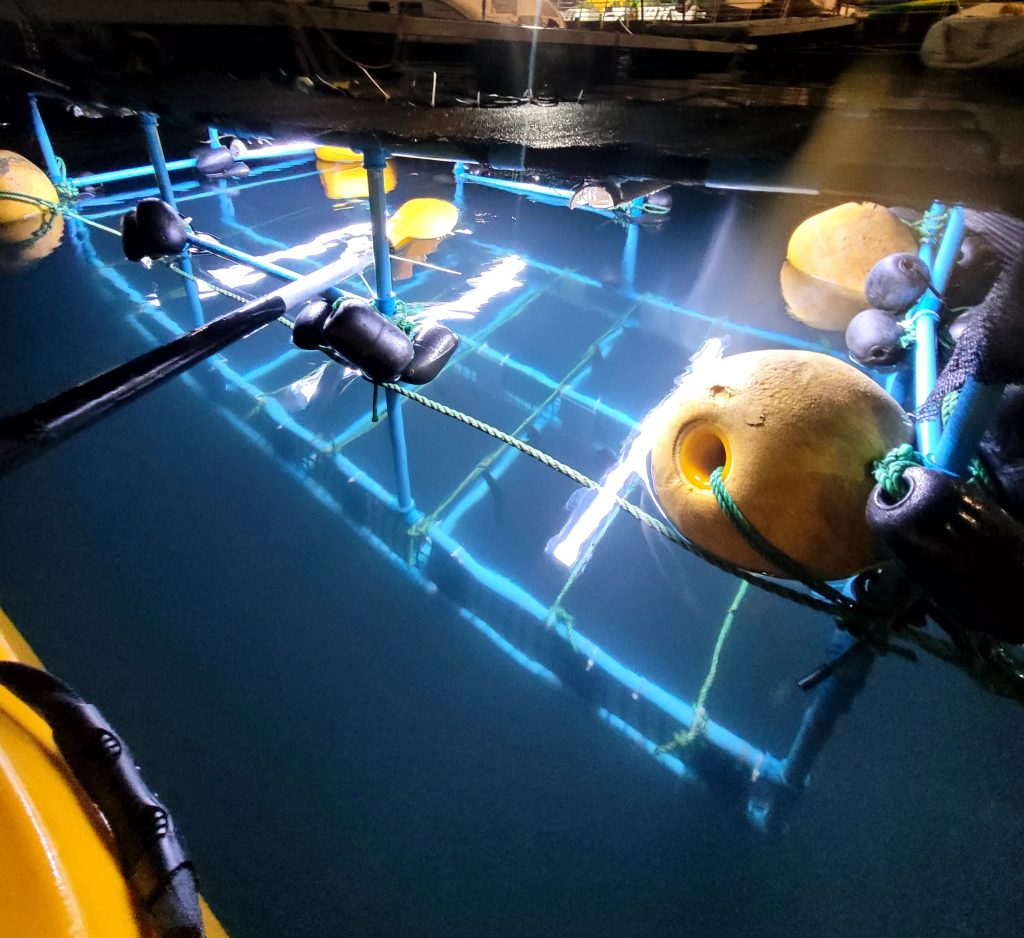

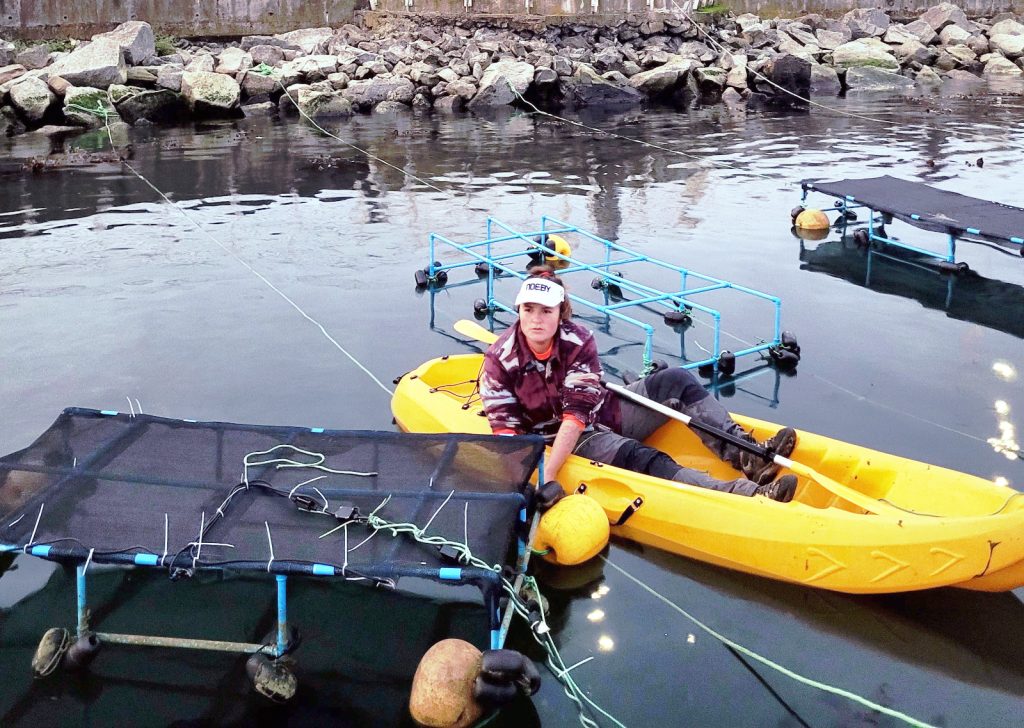

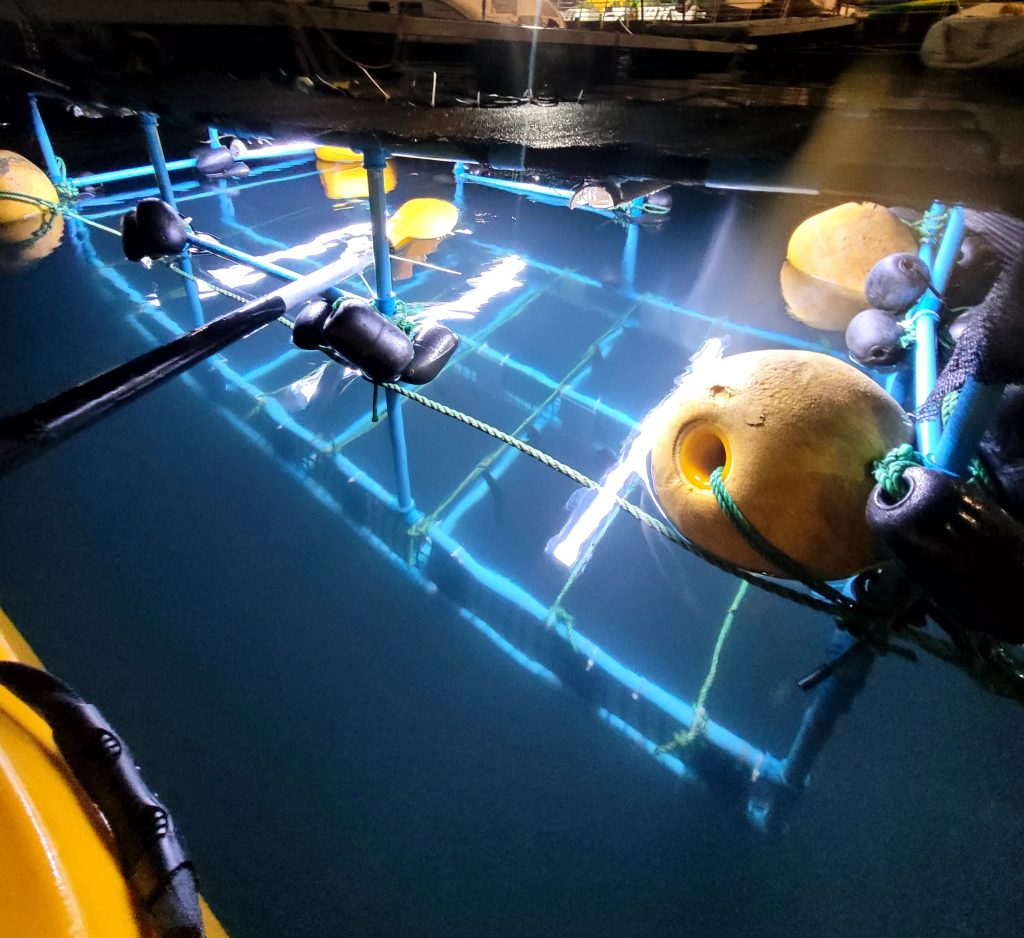

Finally, the aim of our research is to compare the growth and the chlorophyll a content of epiphytes that experience ALAN with epiphytes that do not experience ALAN. For this, we let the epiphytes colonize macroalgae and PVC panels, of which some are exposed to ALAN, while others experience nocturnal darkness. In practice, our experimental setup consists of a submerged frames that are suspended from buoys. Each frame carries the two types of substrate and these remain underwater for 2-3 weeks, while they are exposed either to darkness of to different intensities of artificial light each night. After exposure, we assess the biomass of the epiphytes and also the concentration of photosynthetic pigments (chlorophyll a).

So far, that´s the theory, but at some point we arrived in Chile with the mission to bring these plans to life and reality. Actually, setting up a floating structure in the Pacific Ocean is not exactly plug and play. We had to source local materials, adapt the experimental design to unpredictable swells, strong storms, and curious visitors (both human and non-human). And of course, we had to find the right macroalga to serve as a substrate.

As Concepción is not directly on the coast, we are working in three different places. Our base is the office that the university offered us. There, we are directly on the campus and we can enjoy lunch breaks in the cafeteria with other students and we have easy access to the different facilities of the university. In the building of the science faculty, we use the laboratories, where the friendly lab technicians support us a lot.

However, the most beautiful place of the university is the marine biology station in the Caleta Lenga. A “Caleta” is a small fishermen village. Thus, in Lenga, we might not have access to the cafeteria, but to a lot of empanada stands, where they offer all kinds of seafood empanadas. But this is not the reason why this place is our favourite: The station lies close to the ocean and its rocky shores. You can observe different sea birds, the fishing boats and, a bit less romantic, a pipeline. To get there, you walk along a black beach, which consists of volcanic sediment. You can directly discover the whole peninsula through small paths leading to more beautiful views and beaches. In the station, a lovely little dog called Marta and friendly workers of the biology station are welcoming us.

There at Lenga, werepaired the frames that were used by a previous GAME team in 2023, cut PVC panels and sticks from the structure, sanded the panels for more adherence, and sealed the electric system to make it waterproof. We also tested different light parameters and collected algae in the ice-cold water to fix them to the frames.

After scouting several rocky intertidal areas along the coast, we finally found promising algae close to the marine biology station. To collect seaweeds in the intertidal zone, we must organize ourselves according to the tides, to be out when the tide is low. We need to use wet suits, because we get splashed by the cold waves, but at least we can collect the algae when they are outside of the water.

At this point, we needed to decide between two different algae species Sarcothalia crispata or Mazzaella laminarioides. As Sarcothalia crispata is a subtidal species, which is hard to collect by reaching out from spots in the low intertidal while the waves are breaking, we were quite happy as we found out that the intertidal Mazzaella laminarioid carried more epiphytes in a test run for our experiment than Sarcothalia crispata.

We collected more than 60 seaweed individuals per day, on 2 days in total, with the help of knives and bags to store them in. By the way, the same challenge of the ice-cold water encountered us when we attached and retrieved the algae from the frames. Luckily, when people from the sailing center saw us swimming in the water, they offered us a kajak, so we can more easily retrieve the substrates from our frames and without freezing.

Once the frames were prepared for their mission, we transported them to our study site in Talcahuano, which is a sailing club. Talcahuano is a port city directly connected to Concepción. A big surprise for us was the small sea lion colony in the port. These lazy giants are often lying close to our frames and observing us. Both, we and them, agreed silently on keeping a respectful distance and (in our case) using them as impressing photo models.

Unfortunately, when we inspected the study site we came across another challenge: We already have light pollution there. Buildings close to the cost, boats anchored offshore, and even lighthouses contribute to a constant background glow that reaches the water’s surface. This unexpected discovery shows one more time how pervasive ALAN really is. To exclude this, we tried a lot of different methods and, finally, we decided to cover three of the frames with a net, so that the light that comes from the close streetlights is reduced. The fourth frame will serve as an additional control to see if the net is having any impact on the colonization of the substrates.

Once we were done with the preparations, we started the first experiment on the first days of June. We faced some delays in securing all the necessary lab supplies for the sampling procedure, but after overcoming these challenges, we were able to retrieve the substrates after 21 days. Shipping parcels in Chile requires a bit more patience than in Germany, which contributed to the delay. Additionally, the extended experimental period of three weeks was necessary due to the low temperatures and reduced settlement rates typical of the austral winter.

The week in which we retrieved the substrates was quite intense – sometimes we worked from 7:30 am to 10.30pm. Both of us were happy when the week was over and we had successfully retrieved all substrates. Unfortunately, some of the algae had degraded during the experiment or were missing completely. To get an idea whether there was an effect of ALAN on the epiphytes, we are now in the process of reviewing the data.

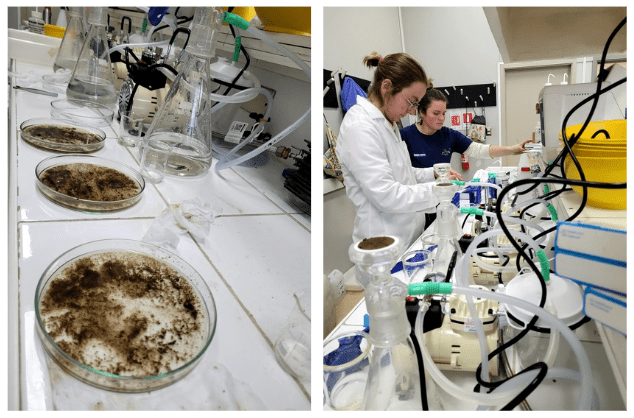

After retrieving the substrates from each frame and placing them individually in sealed and labelled plastic bags, they were transported in a cooler with ice packs and in darkness to the laboratory at the Catholic University of the Holy Concepcion (UCSC). Each substrate was scraped with a brush to remove the ongrowth, then some crawling little mobile animals were separated from the epiphytes by hand, and the remaining biomass was then collected on a filter. As we had two sub-replicates for each replicate, one of them underwent a chlorophyll analysis, while the other sub-replicate underwent an assessment of the epiphytic biomass.

Now, the data analysis will take some time, as we both need to organize ourselves a bit: Bianca needs to defend her Bachelor thesis and Lou needs to leave the country to get a new visa. Another important lesson we learned: There are always a lot of surrounding issues that come with a research project but are not necessarily connected to it.

To sum up, as every GAME team, we had our challenges but until now, we are proud that we could find solutions for them and we are looking forward to the second and the third experiment in Concepción, Chile.

In the upcoming weeks, we´ll continue with our experiments, collecting data and diving into their analysis. We hope to understand how artificial light at night (ALAN) may influence the delicate relationship between macroalgae and epiphytic communities.

This is just the beginning-not only of our scientific findings, but also of important conversations we hope to initiate with coastal communities, decision makers, and other researchers. Light is often associated with safety and progress, but through this experiment, we are learning that even light has a dark side.