Mabuhay from Team Philippines!

For the first time in the programme’s history, GAME takes place in the tropical country of – The Philippines! Composed of 7641 islands, the Philippines is an archipelagic country, surrounded by the waters of the South China Sea on its western seaboard and the Pacific Ocean on its eastern seaboard. Literally speaking, the Philippines has more water than land! In this year’s GAME project, Team Philippines is joined by Jonh, a student at The Marine Science Institute of the University of the Philippines (UPMSI), and Caro, the German counterpart from the University of Rostock – both are pursuing a career in marine biology.

After a month of careful planning in Kiel for the field experiments, we are now stationed at the Bolinao Marine Laboratory (BML) of UPMSI. In early April, Caro arrived in Manila, the capital city of the Philippines, and was greeted by the warm and humid summer weather of the country. We then travelled together for about 8 hours by bus to Bolinao, Pangasinan, where BML is located, and where the GAME project will take place.

Before sharing with you what, we’ve been doing and what we will do in BML for the coming months, allow us to provide you some background information about the marine station where we are. The Bolinao Marine Laboratory (BML), situated in the municipality of Bolinao in the province of Pangasinan, is the main research station of UPMSI. It is in the northern corner of the Lingayen Gulf in the northern Philippines. The town of Bolinao is rather small, and the town centre is around a 10-minute tricycle ride away from the institute.

One of the unique features of the BML is its outdoor hatchery. The hatchery consists of several experimental areas as well as culture facilities managed by different research groups studying hard and soft corals, sea cucumbers, sea urchins, giant clams, and seaweeds among others. The Algal Ecophysiology Laboratory, where Jonh is affiliated, is operating an outdoor land-based nursery for different eucheumatoid seaweed species. These eucheumatoids are commercially important seaweeds due to their phycocolloid content – called carrageenan. Hence, they are commercially farmed in many coastal communities in the Philippines and other tropical and sub-tropical countries. Can you guess where carrageenan is used? Look at your moisturising cream or shelf-stable dairy products, and you might find carrageenan among the ingredients! Thankfully, this nursery will be our source of macroalgae for our experiments.

The BML offers student accommodation in two dorms, which are located just a few meters away from the institute’s main laboratory building. This makes it easy for us to quickly check our setup early in the morning, when the heat is not as bad yet. But here, nothing goes before having a good cup of coffee in the morning. Jonh’s coffee is so strong that it could even wake up the dead.

The coastal waters in front of BML are quite productive. One of the reasons for that is the decades-long farming of milkfish (Chanos chanos) nearby, which is releasing nutrients into the environment. In addition to that, there are also outflows of groundwater that contribute to the nutrient load in the area, because they are influenced by farming in the upland. Hence, when you look at the seagrass growing here, you can see that almost every seagrass blade is heavily colonised by epiphytes. Also in the seaweed nursery, epiphytes are a common problem. The cultured seaweeds there need to be cleaned from epiphytes every few weeks to keep them healthy. In addition, the rocks in the intertidal just in front of the hatchery are also covered by various fast growing macroalgal species, including Ulva spp. and Caulerpa spp., among others.

This year’s GAME project is again about light pollution. We will investigate the influence of artificial light at night (ALAN) on epiphytes that grow on macroalgae. Potentially, the epiphytes can make use of the low light intensities of ALAN, for instance for their photosynthesis, and can by this benefit from light pollution. If this is the case, it could be that not only the release of nutrients enhances the abundances of epiphytes, but also light emissions coming from streetlights, buildings, ports and vessels along the coast. In many sea areas, epiphytes are an environmental problem, because they limit the amount of light, nutrients and gasses that larger macroalgae can take up. With this they impair their performance and can limit macroalgal growth and reproduction.

Like the GAME project in 2023, we will conduct a field experiment, using frames that we will deploy in the sea and to which we will fix substrata for the epiphytes to grow on. We planned to use macroalgae as well as PCV panels as substrates for the epiphytes. Since this is the first time that GAME is taking place in the Philippines, there are no frames from previous projects at site, and we had to start from scratch.

So, during the first few days of our stay in BML, we were busy buying all the materials for our field experiment. One of the first problems we encountered was finding PVC panels. None of the local hardware stores in Bolinao had PVC panels or any other suitable material. Therefore, we decided to go to a nearby city, Alaminos, and continue our hunt there while braving the scorching summer heat. Unfortunately, also after visiting multiple stores, we were not able to find PVC sheets. Luckily, in the last hardware store, we could buy some vinyl tiles, which are a suitable alternative.

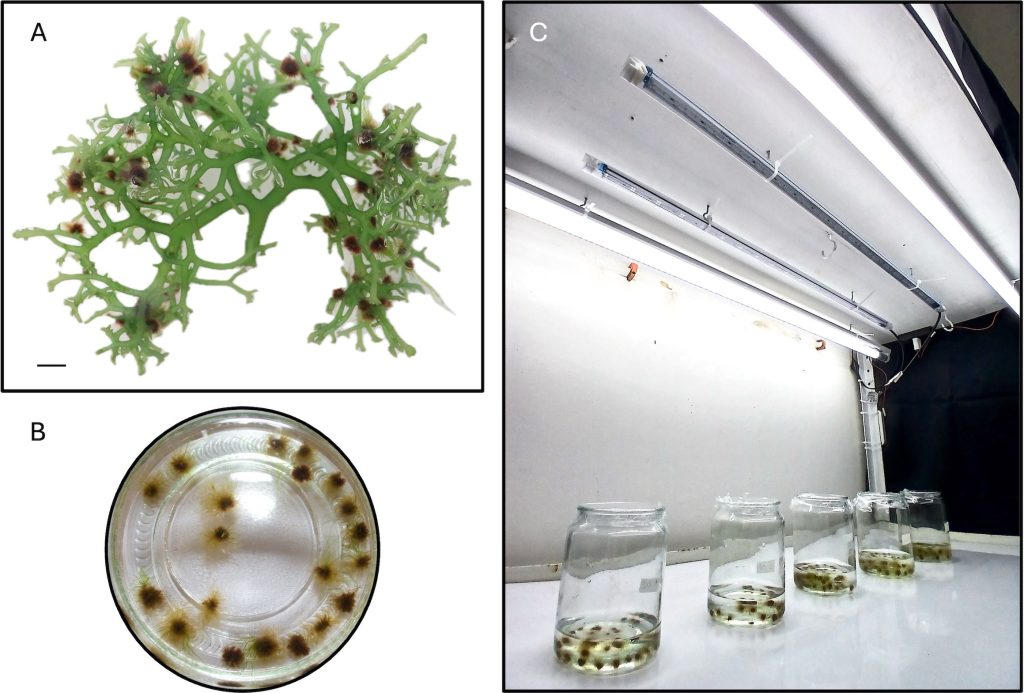

Meanwhile, while waiting for our materials to be delivered and our floating and underwater frames to be constructed, we did some small laboratory experiments. When we arrived in BML, we noticed that there was a bloom of epiphytes in some of our cultured eucheumatoids. So, we decided to isolate them by using a blade to remove them from the surface of the larger macroalgae and acclimatize them to the lab conditions. The isolated epiphytes were composed of at least three macroalgal species. We then initially exposed them to different night-time light regimes, i.e., no ALAN, ~10 lux, ~20 lux, and ~30 lux ALAN, and measured the oxygen evolution under these treatment levels after a few days of pre-exposure. The results of this short experiment were quite interesting. The photosynthesis of the epiphyte complex did not seem to be triggered after 5 days of exposure. Additionally, ALAN did not show a significant effect on the uptake of inorganic nutrients which is important for the epiphyte’s growth. For the eucheumatoid seaweed farming industry, this is good news! This implies that the current level of light pollution will seemingly not exacerbate the negative effects of nutrient pollution on the growth of epiphytes on eucheumatoids. But like any other research, experimenting to answer one research question often leads to further questions. And we will try to answer some of these questions in the coming months. Once we have processed all the data of this side experiment, we will be glad to share the results with you.

After all the materials had been delivered and the construction of frames was finished, it was time to deploy them in the sea. Compared to some other teams who must deploy their frames in harbours or jetties, we are lucky and can deploy our frames just in front of the BML. Since the area around the coast of Bolinao is characterized by shallow reefs, our set-up is located around 150 m seaward of the water line. The deployment itself went rather smoothly, mainly because we had many helping hands. For example, when we were running out of rope, one of our labmates even went to the hardware store to buy additional ropes for us while we continued working in the water.

Because the coastal water in Bolinao has extensive seagrass meadows, siganids (rabbitfish) locally called “dangit” are common inhabitants, and are known to graze on seagrass and seaweeds. So, for our test deployment, we decided to use three eucheumatoid species, that is, Kappaphycus alvarezii, Kappaphycus striatus, and Betaphycus gelatinus. We did this to check if the siganids prefer a certain eucheumatoid species, and if so, the least preferred species will be used as the living substrate for our field experiment. Additionally, in case it turns out that all species were eaten by the siganids, we will then put up nets around the setup to prevent them from going near the floating frames.

At present, we are monitoring our test deployment to verify that our construction is not falling apart and to estimate how quickly epiphytes will colonize both, our living and non-living substrates. Even after only six days, plenty of epiphytes had established on our frames and the vinyl panels we deployed. In contrast to this, the seaweeds we deployed are still very clean. Presumably, they have good defense mechanisms against epiphyte overgrowth. Fortunately, we did not observe signs of grazing in any of the macroalgal species we deployed.

Before we can start our first experiment, we still need to integrate the LED system into our setup. This is a complicated process, since we must install new wires to be able to connect our frames to the power supply in the main laboratory building. Gladly, Kuya Chris, the institute’s electrician helped us with that task. No jetties with an existing wiring system? We managed to solve this with the help of Kuya Chris and Kuya Rene. Guess what we used? The locally growing bamboo! We then attached each bamboo pole to an angle bar hammered into the seafloor. Then, the electric wires were installed starting from the main laboratory building and were hanged to the bamboo poles until it reached the setup.

Over the weekend, Caro got the chance to visit the giant clam nursery of BML. The nursery is in the waters facing the Silaki island, which is around a 40-minute boat ride away from the institute. Snorkelling between the giant clams and observing their vibrant colours are definitely an extraordinary experience. But you cannot only observe the beautiful molluscs, you can see many different fishes, sea cucumbers, and corals.

With light pollution in nutrient-enriched waters, how will epiphytes perform in our living and non-living substrates? This will be our guiding question as we will move forward with our field experiments. We are looking forward to getting started with the actual experiments and are excited about what will happen in the upcoming months.

Paalam!

Jonh and Caro