People love spectacular events. And: Bad news sell.

These basic rules in journalism turn maritime disasters into perfect news stories. Yet this applies not only to news: Countless books, dramas, documentaries, and feature films have exploited the great dramatic potential of natural disasters. Accordingly, among the enormous spectrum of topics in ocean research, the general public will always display a special interest in coastal hazards.

The coast is the sensitive zone where man and nature meet. Not just “any nature”, but the ocean – an enormous natural force that man has used and exploited for thousands of years, but rarely begun to understand. Today, the coastal zones around the globe have become more important than ever. The two greatest demographic moves of the past centuries has been people’s move to cities – and people’s move to coasts. 20 of the 30 largest cities in the world are in low-lying coastal areas. This means, they are megacities at risk. These megacities as well as countless smaller communities along the coasts of all continents are potentially exposed to maritime disaster – some more, some less.

Humanists with their expertise in assembling and focussing knowledge, finding new strategies for communication, and networking in interdisciplinary teams can contribute to enhancing the awareness of this risk. Or at least, they can contribute to disseminating knowledge that is based on sound research – beyond the general taste for spectacle and disaster.

Storm Floods

In the countries around the North Sea, the recent storms “Xaver” and “Christian” have intensified our awareness of natural hazards menacing our shores. They have revived the age-old motif of a murderous sea taking back what does not belong to man.

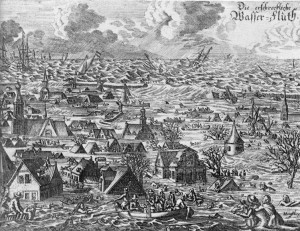

Of course, storm floods are a phenomenon any North Sea state has been living with for hundreds of years. The chronology of storm floods on the North Sea shores is endless, with some events having gained tragic notoriety, such as the Grote Mandrenke (Zweite Marcellusflut) of 1362, the Burchardi Flood of 1634, or the North Sea Flood of 1953. These events have contributed to the mythification of storm floods in the North Sea region, establishing a fixed repertoire of images, such as

- the sea as a roaring monster that comes to devour man and his vain constructions,

- “drunken villages” where, if at all, only the church tower remains over water,

- men, women, children, and cattle fighting helplessly in the floods.

These images – which all are assembled on the 1634 copper print of the Burchardi Flood above – have become an inherent part of the cultural traditions of the coastal regions around the North Sea.

Today, the research on the historical floods not only plays a role in regional history, but also for natural scientists, engineers, and social scientists who try to delineate the long-term development and risks in these coastal regions. Historians, in turn, can transfer their historical and cultural knowledge to the present-day challenges, examining strategies of prevention, such as awareness raising and coastal management. For project integrating both the historical and the contemporary aspects, cf. the post Examples: Humanistic Ocean Research.

Tsunamis – When the Sea Turns Into a Deadly Beast

The Paw of Nature (And We Humans) is the title of an audio drama on the 2011 Tohoku Tsunami written by the renowned film director Alexander Kluge. Here, Kluge unfolds the motif of nature as an untamed beast, beating down on mankind and man’s allegedly superior civilization. Nature cannot be tamed.

The tsunami is indeed the perfect image for this side of nature. While (most) volcanoes at least offer a constant, visible reminder of the latent natural forces that can suddenly beat down on man, tsunamis suddenly turn our beaches and coasts into a watery hell. Just as it so fatally happened with the Indian Ocean shores on 26 December, 2004: From one moment to the other, children playing in the sand, fishermen tending their boats were overwhelmed and killed by the sea that until that moment had been a playmate and a partner to them. A tsunami is not just a wave – it is the entire ocean rearing up and devouring all who believe that the ocean is a pleasure and a friend. To humans, it is an archaic power that with one slap of its paw brushes away our belief in the superiority of technology and civilization.

With the incisive event of the 2004 tsunami, which not only hit numerous countries around the Indian Ocean, but also tourists from all continents, the power and threat of the tsunami has entered global awareness. Filmmakers, journalists and novelists have exploited the archaic imagery of this natural disaster. Scientists, in turn, have had great benefit from this sudden attention, receiving the necessary funds for research, the development of early warning systems, and the enhancement of awareness and preparedness in the endangered regions.

However, there remain unchartered waters on the inner map of our general tsunami awareness. Enjoying your holiday on a lovely Sicilian beach, are you actually aware that the Mediterranean ranges as No. 2 on the international chart of tsunami hazard zones? Do oil companies take into consideration that they actually might destabilize the continental shelf and thus cause larg-scale underwater landslide tsunamis in the North Sea? Have people forgotten about the 1755 earth quake and tsunami that destroyed Lisbon – and do they ignore that seismic events along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge may cause tsunamis that will hit the eastern and western shores along the Atlantic?

Making use of the excellent research of scientists worldwide, humanists can contribute to enhancing awareness and preparedness. As experts in language, communication, and media strategy, they can work together with people active in public policy and risk management, making use of the general fascination with tsunamis to inform the public about concrete risks and possibilities to minimize these risks in the various coastal regions. It need not be the big book or extensive TV documentary – any interview or article placed in a more popular medium is a little contribution.