Even in winter, the sun still has power here in the Aegean Sea. The sky is blue and the mood is good, even though we have a lot to do in these first few days. Underwater, invisible to the human eye, there are many interesting things happening in the region where we are travelling. This is because there is a tectonic weak zone around Santorini with many other active and inactive volcanoes, of which Kolumbo is the best known. As the Christiana-Santorini-Kolumbo volcanic field, which is more than 60 kilometres long, lies at the centre of an active rift system, both seismic and volcanic processes are at work here.

Kolumbo itself is a submarine volcano located about 7 kilometres northeast of Santorini. The deepest point of its caldera is more than 500 metres below sea level, while its crater rim is only about 18 metres below sea level at its shallowest point. The crater has an impressive diameter of almost 1.8 kilometres. The area around Kolumbo is an EU Natura 2000 nature reserve, but is also closely monitored for marine geohazards.

The last major eruption of Kolumbo was 375 years ago, in 1650 CE, and lasted two months, causing extensive damage, particularly on Santorini. At that time, the volcano’s magma dome collapsed, creating the caldera we see today and triggering a devastating tsunami. Seismic activity continues to occur in the vicinity, most recently intensifying in early 2025. Although there are no indications of any imminent further events, the region is being monitored for hazard analysis and is of great interest to us, as we can gain new scientific insights from this dynamic system.

We learn this and much more from a lecture by Paraskevi Nomikou, whom we call Evi. She has been researching Kolumbo for years and explains how the current state of knowledge is based on numerous research missions. She was already a part of research missions to Kolumbo in the early 2000s. This means she can report first-hand when which areas of the underwater volcano were first discovered and mapped, and she knows the hydrothermal vents at the bottom by name. The ‘Witches Hat’ – like the name implies – looks like a witch’s hat, and the ‘Champagne’ continuously bubbles with so many gas bubbles that it immediately brings a freshly opened bottle of champagne to mind. Our cruise is thus part of a series of scientific missions to uncover the secrets of Kolumbo. Short scientific lectures will now regularly be held on board by members of the team for anyone who has time. These usually cover topics relevant to the current measurements, such as overviews of the region, experiences from previous measurements, or the exact working principle of the specific instruments. This leads to a lively exchange between the working groups of the various different instruments that we use on this cruise.

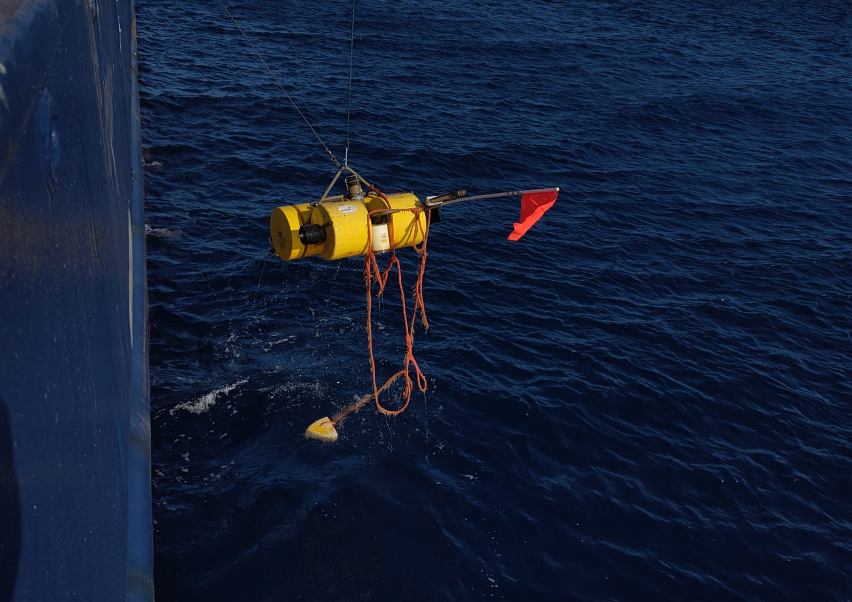

From the morning of 18 December – we are still at Kolumbo – ocean bottom seismometers (OBS) are being recovered here, which provide us with data on seismic activity. A total of eight instruments rise to the sea surface one after the other after their release mechanism has been triggered and the ocean bottom seismometers are pulled upwards towards the light by the buoyancy body. Once they float on the surface, we can bring them on deck. This requires excellent teamwork and a keen eye for the right moment to catch the OBS before it can float past the METEOR. It is then lifted on board with a crane. Now we have access to the data that have been recorded since deployment and that we have been waiting for! But not too quickly, because first we have to extract it from the measuring devices. Almost all of the ocean bottom seismometers show signs of their long stay in the seafloor: they are covered by a carbonate crust, and their screws in particular are now so firmly stuck to the bottom due to a chemical reaction that they first have to be soaked in acid before they can be loosened. Everyone pitches in to help, including some of the senior scientists, who find this task brings back nostalgic memories of their own time as student assistants. Five of the eight OBSs will be redeployed at the end of the voyage to collect further data. So, we now have time until then to polish the selected five back to their former glory.

An ocean bottom seismometer is recovered. Photo: Johanna Salg, GEOMAR

In the afternoon, further tests of the MOLA landers in water follow. The main focus is on ensuring that no water penetrates the capsules, which will later transport the sensitive electronic measuring instruments to the sea floor. For this reason, the capsules will initially be lowered into the water without measuring instruments.

Once all the equipment has been prepared, tested and calibrated, it will be put into action over the next few days! But more about that next time.

Wintery greetings at 18°C

The M215 (MMC-3) team