[English version below]

Hey Acesta, sag mir wie warm es ist!

Eine Wassertemperatur zu bestimmen ist nicht schwer. Man muss nur ein Thermometer ins Wasser halten und die Temperatur ablesen. Die Wassertemperatur der Meere vor 30 Millionen Jahren zu bestimmen, ist wesentlich komplizierterer, da Zeitreisen noch nicht für jeden erschwinglich sind. Allerdings können wir trotzdem die Temperatur der Ozeane in der Vergangenheit bestimmen. Wie, fragt ihr? Mit der Hilfe der Muschel Acesta excavata oder anderen marinen Organismen, die ihre Schalen und Skelette aus Kalziumkarbonat (das Zeug, das die Wasserleitungen verstopft) ausbilden. Aber fangen wir ganz vorne an. Um die Temperatur von Ozeanen in der Vergangenheit zu bestimmen benötigen wir einen Proxy. Ein Proxy ist ein messbarer Parameter im Kalziumkarbonat, der sich in Relation zur Temperatur verändert. Wenn man einen solchen Proxy gefunden hat, muss man ihn kalibrieren, so dass er exakte Ergebnisse liefert. Dabei erstellen wir eine Transferfunktion, die den Zusammenhang zwischen Proxy und Wassertemperatur beschreibt. Das mag jetzt alles sehr kompliziert klingen, aber lasst es mich anhand eines Beispiels verdeutlichen.

Fig.1: Die Muschel Acesta excavata in der toten Riffbasis. Foto: JAGO-Team.

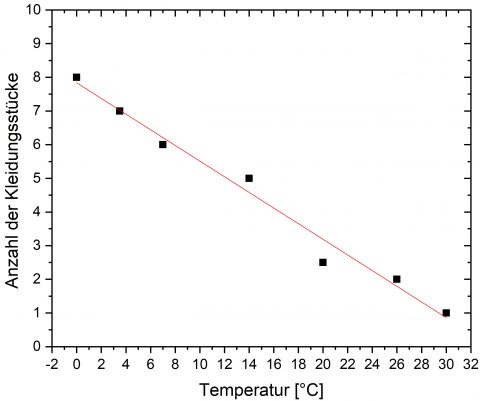

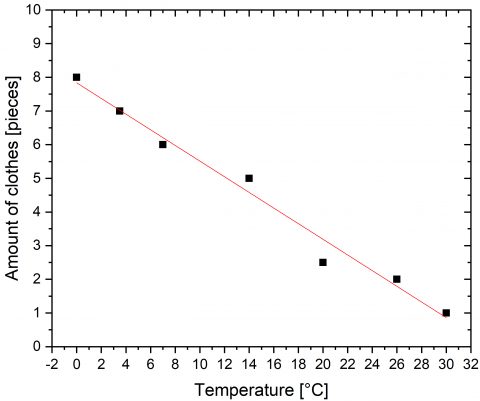

Wenn es im Winter kalt wird, neigen die Leute dazu mehr Klamotten zu tragen. Im Sommer dagegen werden weniger Klamotten getragen. Die Anzahl an Kleidungsstücken, die ein Mensch trägt, wird also durch die Temperatur bestimmt. Das ist ein Proxy. Jetzt muss dieser Proxy kalibriert werden, also messen wir die Anzahl an Kleidungsstücken die Menschen bei verschiedenen Temperaturen tragen. Zum Beispiel messen wir, dass Menschen bei 30°C 1 Kleidungsstück tragen, 8 Kleidungsstücke bei 0°C und so weiter. Wenn wir diese Daten nun in einen Graphen einzeichnen, zeigt sich, dass sich die Anzahl der Kleidungsstücke die ein Mensch trägt mit steigender Temperatur reduziert.

Fig.2: Beispiel-Graph zur Erläuterung der Transferfunktion zur Errechnung von Proxys. C:UsersnicolDocumentsOriginLabAnwenderdateienUNTITLED.opju/UNTITLED/Folder1//Graph1

Aus diesen Daten können wir eine mathematische Funktion konstruieren, die diesen Zusammenhang beschreibt. Das ist die Transferfunktion. In diesem Beispiel lautet diese: Anzahl der Kleidungsstücke = 7,83 – 0,23 * Temperatur. Diese sagt aus das mit jedem Grad Temperaturanstieg 0,23 Kleidungsstücke ausgezogen werden (Damit könntet ihr aus ausrechnen, wie warm eure Wohnung sein muss, damit euer Partner nackt herumläuft). Der nächste Schritt ist, die Funktion zu testen. Dazu kann man die Funktion an Daten von vor 60 Jahren nutzen. Falls sie auch an diesen Daten funktioniert, kann man davon ausgehen, dass sie auch an noch älteren Proben funktionieren würde.

Natürlich sind Muscheln und andere marine Organismen nicht dafür bekannt besonders viele Klamotten zu tragen weshalb wir andere Proxies benutzen müssen. Dabei steht uns eine unüberschaubare Vielfalt an Proxies für allerlei verschiedene Parameter (Temperatur, Salzgehalt, Nährstoffkonzentration, etc.) zur Verfügung. Diese Proxies umfassen Elementverhältnisse, Isotopenverhältnisse, morphologische Parameter usw., jedoch funktioniert nicht jeder Proxy in jedem Organismus gleichermaßen gut. Auch zwischen verschiedenen Spezies kann es Unterschiede geben.

Einer der meist benutzten Proxies ist das Mg/Ca (Magnesium/Kalzium) Elementverhältnis. Im Gegensatz zu unserem Klamottenproxy steigt das Mg/Ca Verhältnis mit steigender Temperatur. Das liegt daran, dass der Einbau von Magnesium in Kalziumkarbonat ein endothermer Prozess ist (der Prozess verbraucht Energie/Wärme). Daher steigt die Magnesiumkonzentration im Kalziumkarbonat mit steigender Temperatur an. Wissenschaftler können nun die Mg/Ca-Verhältnisse in alten Muschel-Schalen messen und daraus die Wassertemperatur berechnen, in der die Muschel gelebt hat. Natürlich sind diese Rekonstruktionen niemals 100%ig korrekt und immer mit einem Fehler behaftet. Ein weiterer Umstand, der solche Rekonstruktionen kompliziert macht, ist, dass die meisten Proxies nicht nur durch einen Parameter kontrolliert werden. Mg/Ca-Verhältnisse werden zum Beispiel auch durch die Salinität und möglicherweise derzeit unbekannten Parametern beeinflusst. Und natürlich, wie schon gesagt, funktioniert nicht jeder Proxy an jedem Organismus gleich gut. An Muscheln und Foraminiferen angewendet, liefern Mg/Ca-Verhältnisse gute Ergebnisse. Bei Korallen jedoch nicht so gute. Trotzdem lassen sich mit Proxies belastbare Ergebnisse erzielen, die für verschiedene wissenschaftliche Fragestellungen genutzt werden können. Wollt ihr vielleicht wissen, was passiert, wenn unsere atmosphärischen CO2-Konzentrationen weiter ansteigen? Schaut euch einfach die Kreidezeit (vor 145 – 66 Millionen Jahre) an. Damals waren die CO2-Konzentrationen mindestens viermal so hoch wie heute.

Natürlich gibt es nicht nur Proxies für marine Lebensräume, sondern auch für terrestrische. Baumpollen können beispielsweise auch für Temperaturrekonstruktionen genutzt werden und Tropfsteinhöhlen, die aus Kalziumkarbonat aufgebaut sind können ähnlich genutzt werden wie Muschelschalen. Allerdings wäre das viel zu viel um das alles in diesem Blog zu erläutern. Wenn ihr natürlich noch mehr Fragen zu diesem riesigen Feld der Wissenschaft habt, dann scheut euch nicht, diese zu stellen.

Nico Schleinkofer

Hey Acesta, tell me how warm it is!

Measuring water temperatures is not difficult. You only have to use a thermometer and put it in the water. But measuring how warm the oceans were 30 Million years ago is far more difficult, because time-travelling is not yet accessible for everyone. But we can still manage to calculate the temperature of the oceans in the past. How, you ask? With the help of the clam Acesta excavata or other organisms that build their skeletons and shells from calcium carbonate (the stuff that clogs your waterpipes). But let’s start at the beginning. To calculate the temperature of the oceans in the past we need a proxy. A proxy is some kind of measurable parameter in the calcium carbonate that changes in relation to water temperature changes. When such a proxy is found we need to calibrate it so it gives us exact temperatures. This process results in a transfer function, which represents the relationship between the water temperature and the proxy. That sounds very complicated but let me clarify it with an example.

Fig.1: The bivalve Acesta excavata in the dead reef framework. Picture: JAGO-Team.

When it becomes cold in winter, people tend to wear more clothes and the other way around. The amount of clothes on a human being is, therefore, directly controlled by the temperature. This is the proxy. Now we need to calibrate the proxy, so we measure the amount of clothes that humans wear at different temperatures. So, let’s say we measure that humans wear one piece of clothes at 30°C, 8 pieces of clothes at 0°C and so on. If we draw this data in a graph we can see that the amount of clothes a human wears reduces with temperature.

Fig.2 Example graph for proxy transfer function. C:UsersnicolDocumentsOriginLabAnwenderdateienUNTITLED.opju/UNTITLED/Folder1//Graph1

We can then construct a mathematical function, which describes this “negative linear relationship” (the higher the temperature the smaller the amount of clothes). This is the transfer-function. In this example the transfer-function is: Amount of clothes = 7.83 – 0.23 * Temperature. This means that for every degree of rising temperature, people undress 0.23 pieces of clothes (you could calculate how warm the flat should be that your significant other walks around naked). The next step is to test this function, so we take some data from 60 years ago and check if the transfer-function fits as well. If it does, we can use this function to calculate the temperature of past times by just measuring the amount of clothes.

Of course, clams and other marine organisms are not particularly known for wearing clothes so we have to use other proxies and there is a huge amount of proxies for all kinds of different parameters (temperature, salinity, nutrient concentration, etc.) such as elemental ratios, isotopic ratios, morphological parameters, etc. However, not all proxies work in every organism and not all proxies have the same transfer-function when used on different species.

One of the most used proxies is the elemental ratio Mg/Ca (Magnesium/Calcium). Contrary to the clothes-proxy, Mg/Ca ratios increase with rising temperatures. This is caused by the fact that the incorporation of magnesium into the calcium carbonate is an endothermic process (the process consumes energy / heat). Consequently, the amount of magnesium in the calcium carbonate shells of clams increases with temperature. Scientists can measure this concentration and can therefore determine the water-temperature the clam lived at. Of course, these reconstructions are not 100% precise and usually include an error. Another problem that makes these reconstructions more complicated is that most proxies are not controlled by only one parameter. Mg/Ca ratios for example are also slightly controlled by the salinity and maybe even other effects that aren’t even known yet. And of course, as already told, not every proxy works in every organisms. Mg/Ca ratios might give good results when used on Clams or Foraminifera (single-celled organisms that usually have a shell), but when used in corals the results are very difficult to interpret and not trustworthy so far. Nevertheless, when handled carefully, proxies give reliable results that can be used for all kinds of different scientific questions. Want to know what happens when the CO2-concentration in the atmosphere rises further? Just check out the Cretaceous period (145-66 million years ago), during that period the CO2-concentration was at least four times higher than today.

Of course, there are not only proxies for the marine environment but also for terrestrial environments. Tree pollen can be used for temperature reconstructions as well and the calcium carbonate in stalactite caves can be used similarly to the calcium carbonate from marine organisms. The possibilities are endless; however, it would be far too much to explain everything in this blog post. Of course, if you are interested in hearing more about this vast field of science, don’t hesitate to ask questions.

Nico Schleinkofer