[German translation below]

On-board experiments

Thirteen days on-board and the experiments are running smoothly. All those wires and cable ties for what, you ask?

Well, my main task on this vessel is to run respiration incubations. I have had help from Tina for a few days and now she has been replaced by the PhD student, Øystein, of our group at IMR. Basically, we do laboratory work, except that instead of being in a lab and sleeping at home, we work on a moving boat and we don’t sleep much.

Sun is up – like me, at 4:15 AM. Picture: Narimane Dorey.

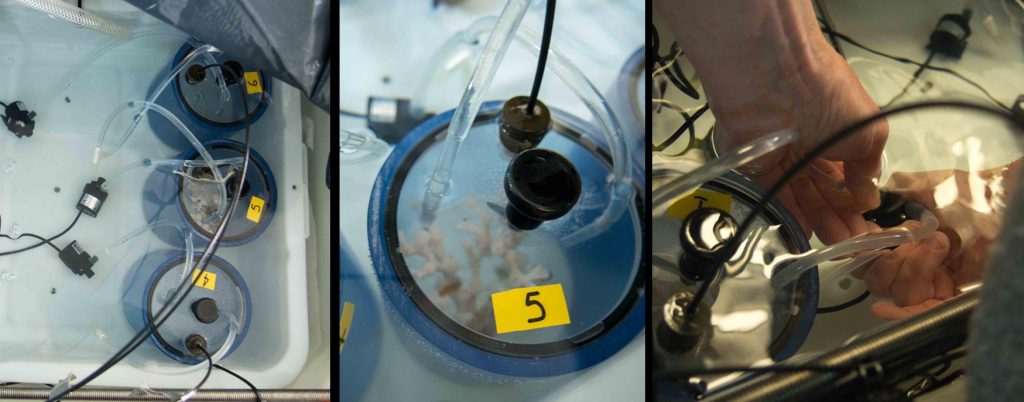

Our very tidy on-bard set-up made of fish tanks, cables, cable ties, and zip-block bags. Picture: Narimane Dorey.

This has big advantages though: we get very fresh corals and seawater, directly from the ocean behind us and we don’t have to transport and acclimatize our corals to lab conditions and can start experiments immediately in conditions that are closer to what happens in reality.

The main question for us is to look at how our corals respond to stress. So, we put them in a water bath (a big tank where we can regulate temperature) and raise the temperature quite rapidly. We start at 5°C increase the temperature to 15°C by steps of 2 degrees every 12 hours. So far, we were quite surprised by the resistance of corals. They look still healthy at 15°, although they live at around 5-8°C in their reef habitats here in Norway.

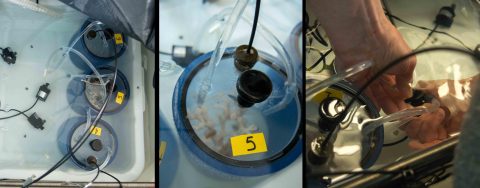

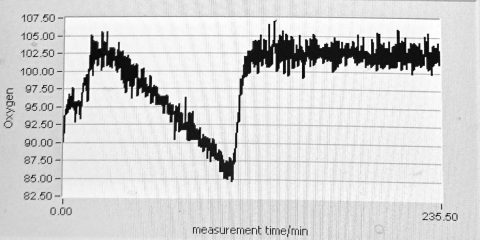

But this is just preliminary “impressions”. We actually measure some numbers, too. We put the coral fragments in closed chambers and we measure oxygen decrease in the seawater of those chambers over time: the drop in oxygen in the chamber is a measure of the respiration of the coral pieces in the chamber that consume the oxygen while breathing. Today and until tomorrow we’re working on corals from the third reef location we are aiming to analyse, with Øystein opening and closing the respiration chambers and me writing down notes.

Corals are in the chambers and pumps for water circulation are being connected. Picture: Narimane Dorey.

What we should see is that respiration goes up with temperature “stress”. It is a bit similar with humans: respiration varies with different parameters: for example when you run, you need to increase your input of oxygen to be able to “feed” your muscles with oxygen. Corals (and many other invertebrates) don’t work exactly like humans, but their respiration increases when temperature increases. This is not new, but what we are particularly interested in is if corals from different reefs respond differently to stress.

For various reasons, we think that the coral reefs that are closer to the coastline of Norway will be more resistant to this temperature stress than the corals that are further away from the coast. This is our working hypothesis for this cruise and this experiment.

Oxygen decrease when we put the coral in the respiration chambers. Picture: Narimane Dorey.

Now, to test this hypothesis, we do the experiment that I described above. We will look at respiration, but we also have other markers of stress that we will look at later in the lab when we are back in Bergen. We hope to see more respiration in the “more stressed” fragile corals and we hope to see differences between different reefs. That would confirm our hypothesis. But, if our hypothesis is not confirmed, it will also be very interesting. This information is very important, especially looking at climate change. If the sea temperature rises by 2 to 4° by 2100 due to climate change as the models predict, it will be very valuable to know which reefs are more “fragile” and need more protection from us.

What is very nice with the crazy shifts that we do on-board is that light is up at all hours and we can see the Lofoten from the vessel in full daylight at 3 AM. This is quite an experience and makes you less tired when getting up in the middle of the night than it would usually do.

Sunset at 3:30 AM at the Lofoten. Picture: Narimane Dorey.

Narimane Dorey

Bord -Experimente

13 Tage an Bord und die Experimente laufen gut. Ihr fragt euch wofür diese ganzen Kabel und Drähte gut sind?

Nun ja, meine Hauptaufgabe auf dem Schiff besteht darin Inkubationen zur Messung des Sauerstoffverbrauchs durchzuführen. Dabei half mir für ein paar Tage Tina Kutti, die nun aber von dem PhD-Studenten Øystein Gjelsvik aus unserer Arbeitsgruppe am IMR (Insitute of Marine Research) in Bergen ersetzt wurde. Eigentlich machen wir normale Laborarbeit, allerdings führen wir die Experimente anstatt in einem Labor auf einem sich bewegenden Schiff aus und anstatt in unseren eigenen Betten zu schlafen, schlafen wir nur wenig und in Schichten, um die Messungen unter Kontrolle zu halten.

Das mag sich hart anhören, hat aber entscheidende Vorteile: wir bekommen frische, lebende Korallen und Meerwasser direkt aus dem Ozean unter uns und müssen die Korallen nicht erst lange transportieren. Dadurch sind die Bedingungen im Hälterungstank an Bord auch viel näher an der Realität im Riff als im Labor zu Hause und die Korallen müssen sich nicht so lange eingewöhnen.

Die Frage die uns besonders beschäftigt, ist, wie Korallen auf Stress reagieren. Um sie unter Stress zu setzten, werden die Korallen in in ihrem Hälterungstank in mehreren Schritten immer höhreren Temperaturen ausgesetzt. Wir starten bei in situ Temperaturen von 5°C und steigern die Temperatur in 2°C Schritten auf 15°C alle 12 Stunden. Bis jetzt sind wir ziemlich fasziniert vom Durchhaltevermögen der Korallen, die bei 15°C noch ziemlich gesund aussehen, obwohl sie im Riff bei 5-8°C leben.

Das sind natürlich nur vorläufige Eindrücke. Natürlich messen wir auch ein paar Zahlen. Dazu setzen wir Korallenfragmente in geschlossene Kammern und messen die Atmung der Koralle. Heute und morgen arbeiten wir noch mit Korallen aus dem Steinavaer Riff. Øystein öffnet und schließt die Kammern und ich mache Notizen zu sämtlichen Beobachtungen.

Was wir sehen sollten, ist das die Atmungsrate ansteigt, wenn sie dem Temperaturstress ausgesetzt sind. Das ist wie bei Menschen, deren Atmung durch verschiedene Parameter beeinflusst wird. Zum Beispiel atmen wir schneller, wenn wir rennen und unsere Muskeln zusätzlichen Sauerstoff benötigen. Korallen und andere Wirbellose funktionieren natürlich nicht genau wie Menschen aber ihre Atmungsrate steigt mit steigender Temperatur. Das ist keine neue Erkenntnis, aber was uns besonders interessiert, ist, ob Korallen von unterschiedlichen Riffen auch unterschiedlich auf Stress reagieren.

Wir nehmen an, dass die Korallenriffe die sich näher an der Küste befinden, nicht so stark auf den Stress reagieren wie Korallen die weiter von der Küste entfernt leben. Das ist die Arbeitshypothese für diese Expedition und dieses Experiment.

Die oben beschriebenen Experimente dienen dazu diese Hypothese zu testen, aber wir benutzen auch weitere Stressmarker neben der Atmungsrate, die wir im Labor messen, wenn wir zurück in Bergen sind. Worauf wir hoffen, ist, dass wir stärkere Atmung in den gestressten Korallen messen und wir hoffen Unterschiede zwischen den verschiedenen Riffen zu finden. Das wäre die Bestätigung für unsere Hypothese.

Aber auch wenn unsere Hypothese nicht bestätigt wird, wäre das sehr interessant. Die gesammelten Informationen sind besonders in Anbetracht des Klimawandels interessant. Wenn die Wassertemperaturen gegen Ende des Jahrhunderts um 2100 um 2 – 4°C gestiegen sind, ist es wichtig zu wissen, welche Riffe besonders empfindlich sind und deshalb besonderen Schutz benötigen.

Wirklich schön an den verrückten Schichten an Bord ist, dass die Sonne immer scheint und wir dadurch die Lofoten um 3 Uhr morgens in vollem Tageslicht genießen können. Das ist eine tolle Erfahrung.