The smallest life at the seafloor (Deutsch s.u.)

by Batuhan Yapan, MPI and Dr. Julia Otte AWI/MPI

The deep sea seems very far away from the perspective of our daily life on land. For comparison, the deep seafloor in the northern Pacific is as far away as the clouds in the sky – about 4000 m far away! From this distance, the seafloor could look a little bit “empty” – in terms of living organisms. A few small animals around the manganese nodules are not what we would call a paradise full of life.

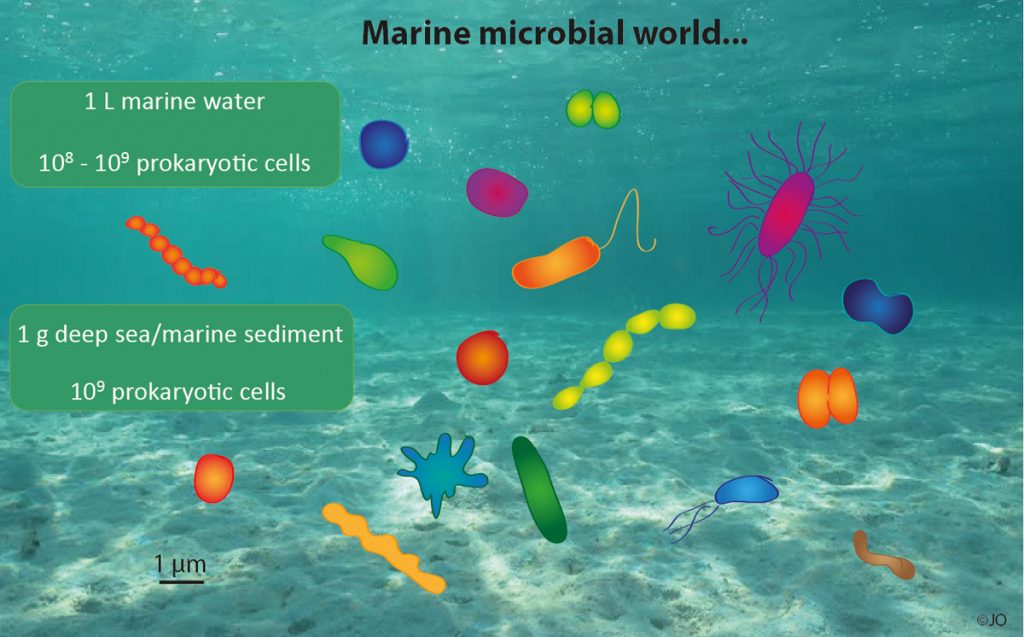

However, if you take a closer look at the seafloor sediments and the bottom seawater (that’s exactly what we are doing on board); you would “see” a crowded and amazingly diverse group of the smallest inhabitants of the deep sea: Microbes! Microbes, or microorganisms, are organisms which can be observed through a microscope. Their size is in the 1-µm range. The definition of microorganisms involves many species from different groups of small life forms: e.g. Bacteria, Archaea, Fungi, and also Viruses (Figure 1 above).

Archaea and Bacteria are in the focus of our recent study. Those organisms are called prokaryotes due to lack of a nucleus and membrane-bounded organelles in their cell in comparison to eukaryotes (e.g. animals and plants). Prokaryotes are everywhere on Earth! So far, it is known that there are microbial communities from several kilometers depth in the Earth’s crust to the upper layers of the atmosphere and they also manage to thrive under ice shelves of Antarctica or in hot springs. In addition, they live very close together! You could count more than a million of them in a drop of ocean water or in the sediment. Deep-sea sediments and also manganese nodules are no exceptions, and they are perfect habitats for deep-sea microorganisms.

Despite their small size, prokaryotes have an enormous effect on life on Earth, global energy and material cycles (e.g. oxygen production, CO2 sink, control gas emission, biomass production, organic matter remineralization, fermentation, nitrogen fixation). Understanding their distribution and activity has crucial importance on understanding life on Earth. On the scientific expedition SO268-2 we try to understand microbial communities and their activity in the seafloor of the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone (CCZ) in the Northeast Pacific.

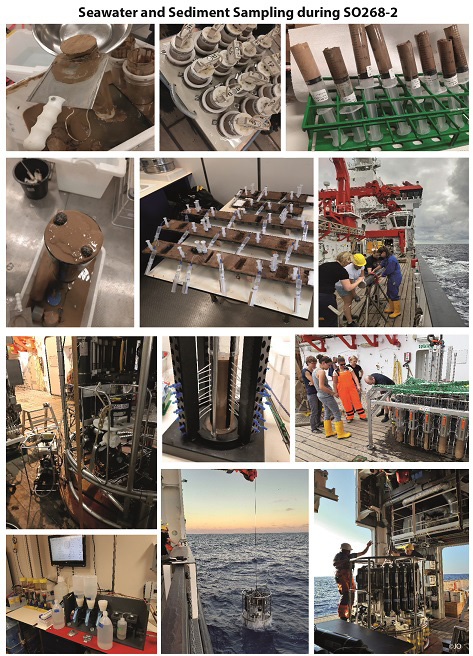

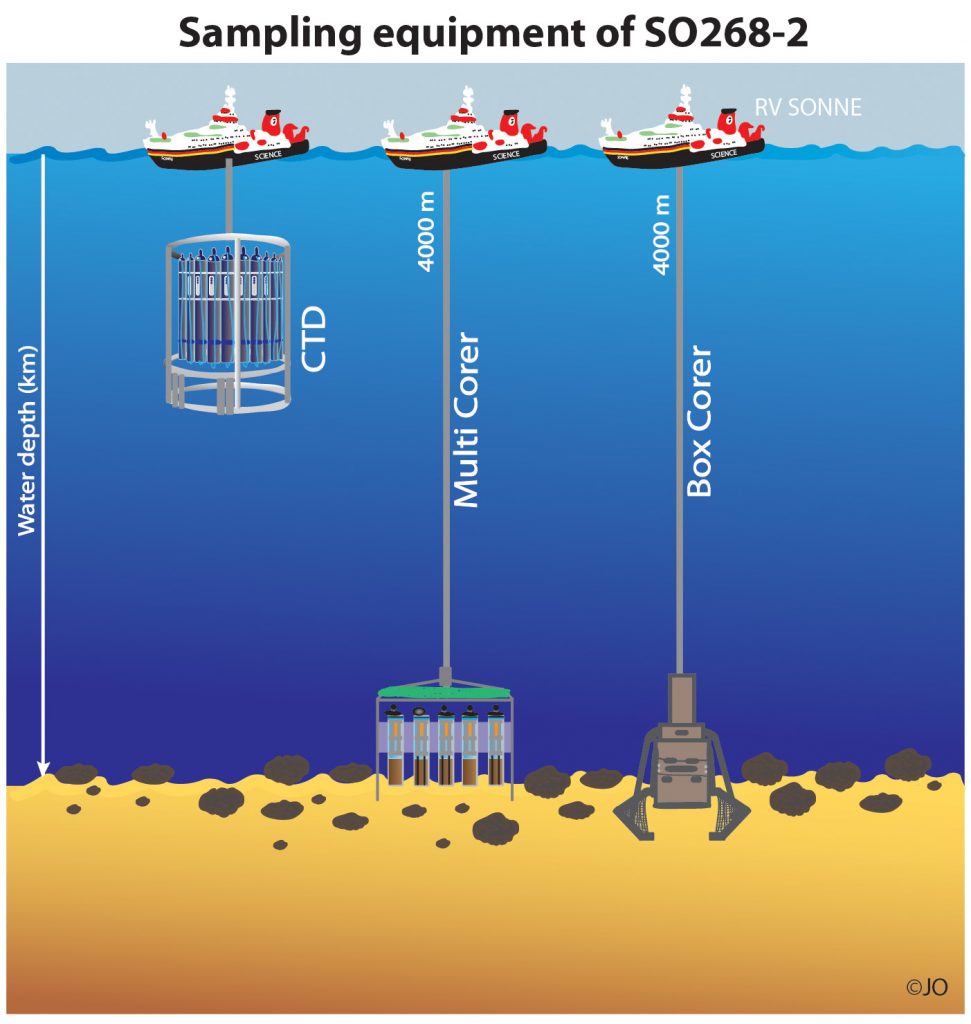

The two investigated areas during SO268-2 have different characteristics: depth, topography, density and size of manganese nodules, and concentration of nutrients coming from the upper water layers. These differences might cause differences in structure and function of seafloor ecosystems. As the microbiology team of SO268-2 we try to answer these questions: Which microbes live at the seafloor? Are they active in the deep-sea sediments and in the manganese nodules? How do they live there? What do they “eat” and how do they impact the global biogeochemical cycles? In addition, how would the microbial community change after mining of the manganese nodules? Can we detect changes in the community before and after a collector deployment? To answer those questions we take samples from (1) manganese nodules, (2) sediments up to 20 cm depth below sediment surface, and (3) seawater samples from different water depths in the Germany and Belgium contract areas (Figure 2 and 3 below).

What are we – as microbiologists – doing on board of SO268-2? Besides slicing sediment cores, filtering of seawater and sampling manganese nodules, we perform microbial activity analyses. The principle of those enzymatic tests is very simple: we give different kinds of “food” to the microorganisms in our samples, and those diverse “food types” are labeled with specific fluorescent dyes. In our experiment we can detect the level of “appetite to different substances” which shows the metabolic activity of the microbes in these habitats. Microbial substrate conversion gives information about functioning of microbial community in this specific ecosystem and the activity level of the microbes at this location.

With the help of extracted DNA and RNA we get details about who is living there in the complex deep-sea community and how do they live; and we will have the opportunity to find new species which give us new perspectives on the microbial world at the seafloor. With cell count analysis microbiologists can answer the question about the total number of microbes and the population size of specific microbial groups.

The potential impact of industrial deep-sea mining on the microbial communities is another important research question of SO268-2. Changes of microbial communities and their activities due to a disturbance might have major effects on global biogeochemical cycles. Therefore, it is important to understand and estimate potential impacts of deep-sea mining on microbial ecosystems. To evaluate impacts, we also took samples from an experimental impact area to compare microbial communities and their activities before and after the disturbance. Preliminary results show already that there is a difference in microbial activity and with the huge amount of collected samples and large data sets we gain a better picture, how the smallest organisms are living in the abyss and how deep-sea mining can impact this fascinating microbial world 4000 m far away from us.

Das kleinste Leben auf dem Meeresboden

von Batuhan Yapan, MPI und Dr. Julia Otte, AWI/MPI

Die Tiefsee scheint – von unserem täglichen Leben an Land – außerordentlich weit weg zu sein. Zum Vergleich: Der Tiefseeboden im nördlichen Pazifik ist so weit entfernt wie die Wolken am Himmel, etwa 4000 m weit weg! Aus dieser großen Entfernung wirkt der dunkle Meeresboden da unten für viele von uns wahrscheinlich sehr “leer” – besonders in Bezug auf lebende Organismen. Die wenigen kleinen Tiere, die einige von Bildern aus der Tiefsee kennen, ist nicht das, was wir ein Paradies voller Leben nennen würden.

Wenn man sich jedoch die Sedimente des Meeresbodens und das Meeresbodenwasser genauer ansieht (genau das tun wir hier an Bord), “sieht” man eine überfüllte und erstaunlich vielfältige Ansammlung der kleinsten Bewohner der Tiefsee: Mikroben! Mikroben oder Mikroorganismen sind Organismen, die durch Mikroskope beobachtet werden können. Ihre Größe liegt im Bereich von 1 µm. Die Definition von Mikroorganismen umfasst viele Arten aus verschiedenen Gruppen kleiner Lebensformen: z.B. Bakterien, Archäen, Pilze und auch Viren (Abbildung 1 ganz oben).

Archäen und Bakterien stehen im Mittelpunkt unserer aktuellen Studie. Diese Organismen werden Prokaryonten genannt, da in ihrer Zelle im Vergleich zu Eukaryonten (z.B. Tieren und Pflanzen) kein Kern und keine membrangebundenen Organellen vorhanden sind. Prokaryonten sind überall auf der Erde! Bisher ist bekannt, dass es mikrobielle Gemeinschaften gibt, die in kilometerlangen Tiefen der Erdkruste bis hin zu hoher Atmosphäre existieren können und es auch schaffen, unter den Eisschelfen der Antarktis oder heißen Quellen zu leben. Außerdem kommen sie meist in sehr engen Gemeinschaften vor! In einem Tropfen Meerwasser oder im Sediment kann man mehr als eine Million Mikroben zählen. Tiefseesedimente und auch Manganknollen bilden da keine Ausnahme und sind perfekte Lebensräume für Tiefsee-Mikroorganismen.

Trotz ihrer geringen Größe haben Prokaryonten enorme Auswirkungen auf das Leben auf der Erde, besonders auf die globalen Energie- und Stoffkreisläufe (z.B. Sauerstoffproduktion, CO2-Senke, Kontrollgasemissionen, Biomasseproduktion, Remineralisierung organischer Stoffe, Fermentation, Stickstofffixierung). Das Verständnis ihrer Verteilung, Diversität und Aktivität ist von entscheidender Bedeutung für das Verständnis des mikrobiellen Lebens auf der Erde. Auf der wissenschaftlichen Expedition SO268-2 versuchen wir, mikrobielle Gemeinschaften und ihre Aktivitäten auf dem Meeresboden der Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone (CCZ) im Mittleren-Nord-Pazifik zu verstehen.

Die beiden untersuchten Gebiete der SO268-2 Expedition weisen unterschiedliche Merkmale auf: Tiefe, Topographie, Dichte und Größe der Manganknollen und Konzentration der Nährstoffe aus den oberen Wasserschichten. Diese Merkmale können zu Unterschieden in Struktur und Funktion der Meeresboden-Ökosysteme führen. Als Mikrobiologie-Team der SO268-2 Expedition versuchen wir, diese Fragen zu beantworten: Welche Mikroben leben im Meeresboden? Sind die Mikroben im Tiefseesediment und in/auf den Manganknollen aktiv? Wie leben sie dort? Was “essen” sie und wie wirken sie auf die globalen biogeochemischen Kreisläufe? Darüber hinaus, wie würde sich die mikrobielle Gemeinschaft nach dem Abbau der Manganknollen verändern? Können wir Veränderungen in der mikrobiellen Gemeinschaft vor und nach einem Kollektoreinsatz erkennen? Um diese Fragen zu beantworten, nehmen wir Proben von (1) Manganknollen, (2) Sedimenten bis zu 20 cm Tiefe unter dem Meeresboden und (3) Meerwasserproben aus verschiedenen Wassertiefen im deutschen und belgischen CCZ-Gebiet (Abbildung 2 und 3 oben).

Was machen wir – als Mikrobiologen – an Bord von SO268-2? Neben dem Schneiden von Sedimentkernen, der Filtration von Meerwasser und der Entnahme von Manganknollen führen wir mikrobielle Aktivitätsanalysen durch. Das Prinzip dieser enzymatischen Tests ist sehr einfach: Wir geben den Mikroorganismen in unseren Proben verschiedene Arten von “Futter”, und diese verschiedenen “Nahrungsmittel” sind mit spezifischen Fluoreszenzfarbstoffen markiert. In unserem Experiment können wir den Grad des “Appetits auf verschiedene Nahrungsmittel” feststellen, der die Stoffwechselaktivität der Mikroben in diesen Lebensräumen zeigt. Die mikrobielle Nährstoffumwandlung gibt Aufschluss über das Funktionieren der mikrobiellen Gemeinschaft in diesem spezifischen Ökosystem und das Aktivitätsniveau der Mikroben an diesem Ort.

Mit Hilfe von DNA und RNA erfahren wir, wer dort in der komplexen Tiefseegemeinschaft lebt und wie sie leben; und wir haben die Möglichkeit, neue Arten zu finden, die uns neue Perspektiven der mikrobiellen Welt auf dem Meeresboden eröffnen. Außerdem können Mikrobiologen anhand von Zellzählanalysen die Frage nach der Gesamtzahl der Mikroben und der Populationsgröße bestimmter mikrobieller Gruppen beantworten.

Die möglichen Auswirkungen des industriellen Tiefseebergbaues auf die mikrobiellen Gemeinschaften sind eine weitere wichtige Forschungsfrage an Bord von SO268-2. Veränderungen in den mikrobiellen Gemeinschaften und ihren Aktivitäten aufgrund einer Störung des Ökosystems können erhebliche Effekte auf den globalen biogeochemischen Kreislauf haben. Daher ist es besonders wichtig, die möglichen Folgen des Tiefseebergbaues auf die mikrobiellen Ökosysteme zu verstehen und abzuschätzen. Um die Auswirkungen zu bewerten, haben wir auch Proben aus dem experimentellen Testbereich (sogenannte „trial area“ nach einem „dredge“ Versuch) entnommen, um mikrobielle Gemeinschaften und ihre Aktivitäten vor und nach den Störungen zu vergleichen. Erste Ergebnisse zeigen bereits, dass es einen Unterschied in der mikrobiellen Aktivität gibt.

Mit der großen Menge an gesammelten Proben gewinnen wir ein besseres Verständnis davon, wie die kleinsten Organismen in der Tiefe leben und wie z.B. ein zukünftiger industrieller Tiefseebergbau diese faszinierende mikrobielle Welt – 4000 m von uns entfernt – beeinflussen kann.