On board of the Research Vessel Meteor, we are currently sailing through the western tropical Atlantic. This region is particularly interesting for me, Josephine Herrford, and other oceanographers, as it represents a crossroad for different currents transporting water from all kind of remote regions around the globe. In oceanography, “water masses” are a fundamental, but also sort of an abstract concept. Atmospheric conditions like precipitation, temperature or winds influence the characteristics of water at the ocean surface. In certain regions, this leads to the formation of dense waters, which – being heavier – have to sink down and stratify themselves according to their density. As soon, as those waters leave the surface, we assume they behave like enclosed volumes, keeping the characteristics imprinted on them at the surface. These “packages” or “water masses” are typically captured by the currents and then transported away.

In the western tropical Atlantic off Brazil different currents and water masses meet: In the upper 1000 meters of the water column, salty water masses coming all the way from the Indian Ocean encounter really fresh water masses formed in the strong Antarctic Circumpolar Current. At deeper layers, enormous volumes of highly oxygenated waters formed in the North Atlantic sandwich in above the coldest and densest water of all oceans formed on the Antarctic shelf, both creating an abyssal stratification.

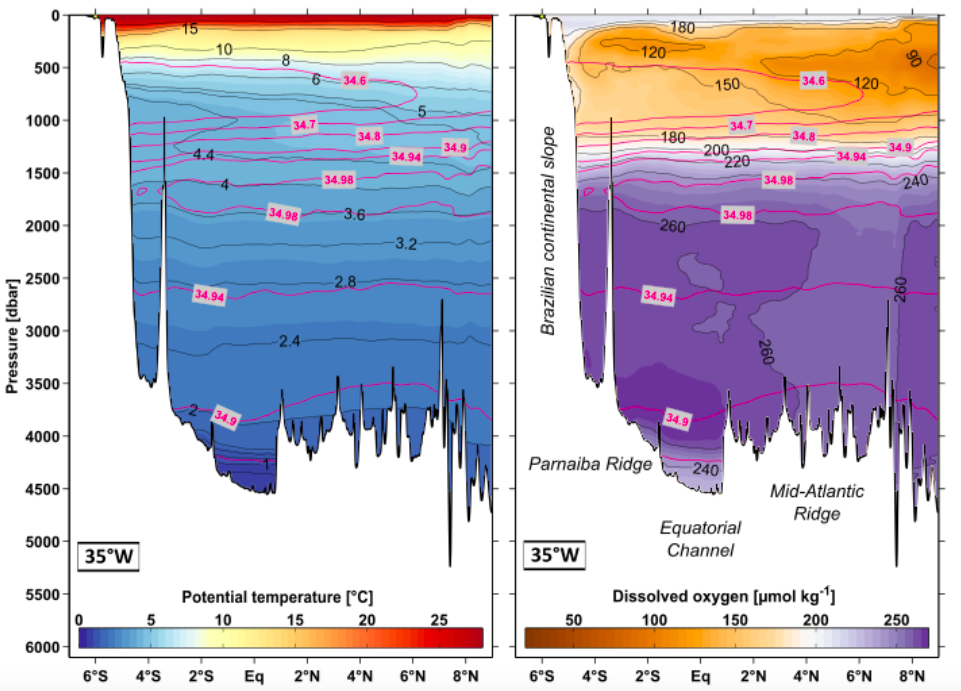

After working on that topic for a couple of years now, I am still fascinated by the scales: Some of these water masses have been isolated from the surface for several decades, just travelling through the ocean and interacting only a little bit with other water masses or the topography. Some had to travel ten thousands of kilometers until they arrived off the coast of Brazil. Some make up 20 – 30% of the global ocean volume. The coldest waters formed around Antarctica, for example, have been found to fill all abyssal planes of the Southern Hemisphere. And, we oceanographers can come to this special region with a ship, lower some sensors attached to a CTD (conductivity-temperature-depth; see figure 2) on a rope down to 4000 to 5000 meters depth and look at the measured temperature or oxygen distributions (see figure 1). With this – also fairly old – technique we are able to recognise all of the water masses mentioned above as well as to infer their origins.

Written by Josephine Herrford, GEOMAR 2019

Does the CTD – measurements follow a systematic survey design and how can you infer the origins of the water masses from ‘simple’ CTD – measurements?

Dear Eva-Lisa,

thanks for your question. Water masses get their characteristics imprinted on them at the surface, when in contact with the atmosphere. As soon, as they leave the surface and travel with the currents, these characteristics are kind of preserved for quite some time and over large distances. At a certain ship-station, the CTD-system is lowered down to the ocean bottom, recording all kinds of variables on its way. In the vertical distributions of temperature, salinity, oxygen etc. we can see different minima, maxima or curvatures, which are related to the characteristics of single water masses. For example, Antarctic Intermediate Water can be found almost everywhere in the South Atlantic and easily identified by its pronounced salinity minimum.

What do you mean with “systematic survey design”?

Cheers,

Josefine