Dobar dan from Pula, Croatia!

A few months ago, nobody even planned that there would be a “Team Croatia”. In fact, all three of us team members – Marie & Franz from Kiel, Germany and Anamarija from Umag, Croatia – were having different plans and never expected to spend the summer together in the wonderful city of Pula.

But let’s start at the beginning. About one year ago, in the spring of 2020, the first preparations for the GAME project 2021 started. We successfully registered as participants and chose our preferred countries of destination to conduct our experiments. Franz planned to go to Cape Town in South Africa, Marie was eager to travel to Penang Island in Malaysia and Anamarija aimed to gain practical experiences with a stay abroad.

As you might imagine, things changed a bit: COVID-19 entered the scene. While the virus was turning our day-to-day lives upside-down, we waited anxiously how the situation and our travel plans would develop. In December 2020, after a lot of hoping and some back-and-forth, it became clear that Franz would not be able to go to his initial destination because of the pandemic. That was the moment, when the Morska škola in Pula as an alternative site and, a little bit later, Anamarija as his team partner, came into play. Finally, in May 2021 it was clear that also Marie would not be able to go to Malaysia and she was then kindly invited to join Team Croatia. Voilà – that’s how we became the first 3-partner team in the history of GAME!

To set the stage for our project, all GAME participants met in an online seminar in March 2021 to work out the experimental design and statistical approaches. During this month, we defined the aims of our study and planned our laboratory set-up. Numerous passionate debates about tiny experimental details were interspaced with the classic challenges of the Zoom format (“Can you hear me? Hello?”, “My internet is a bit sl-l-l-ow right n-n-n-ow.”, “I think he’s frozen again. Okay, yes. Yes, he’s gone.”)

Once everything was clarified in theory, we moved into the practical planning phase: we ordered equipment, such as LEDs, light loggers and cameras. And after we received our final “Go”, we were on the way to Croatia!

Our research base for the next four months is the welcoming Morska škola (or “Meeresschule”), which is located in one of Pula’s countless little bays, near the southern tip of the Istrian peninsula. And yes – we wake up every morning with a charming view on the Adriatic sea. At Morska škola, we found a supportive team, as well as a highly dedicated on-site supervisor (Hi, Gerwin 🙂 ).

Topic of the GAME project 2021 is to investigate the effect of artificial light at night on benthic invertebrate grazers. Light pollution is an emerging anthropogenic issue of global significance, driven by e.g. increasing coastal populations, global shipping trade and tourism. Over 20% of the world‘s coastlines are currently exposed to light pollution, with the consequences for marine species not yet fully understood. Many marine animals regulate their behaviour by using light as an important source of information. Disruption of the day-night cycle can therefore affect the activity of benthic species and subsequently alter food web interactions.

For GAME 2021, we wanted to take a closer look at two possible effects of light pollution on grazers. For this, we will expose our test animals to three light regimes and assess changes in their feeding activity, as well as in their grazing behaviour. Our control group will be kept under a normal day-night rhythm, while our two treatment groups will experience low intensities of artificial light at night with different exposure times.

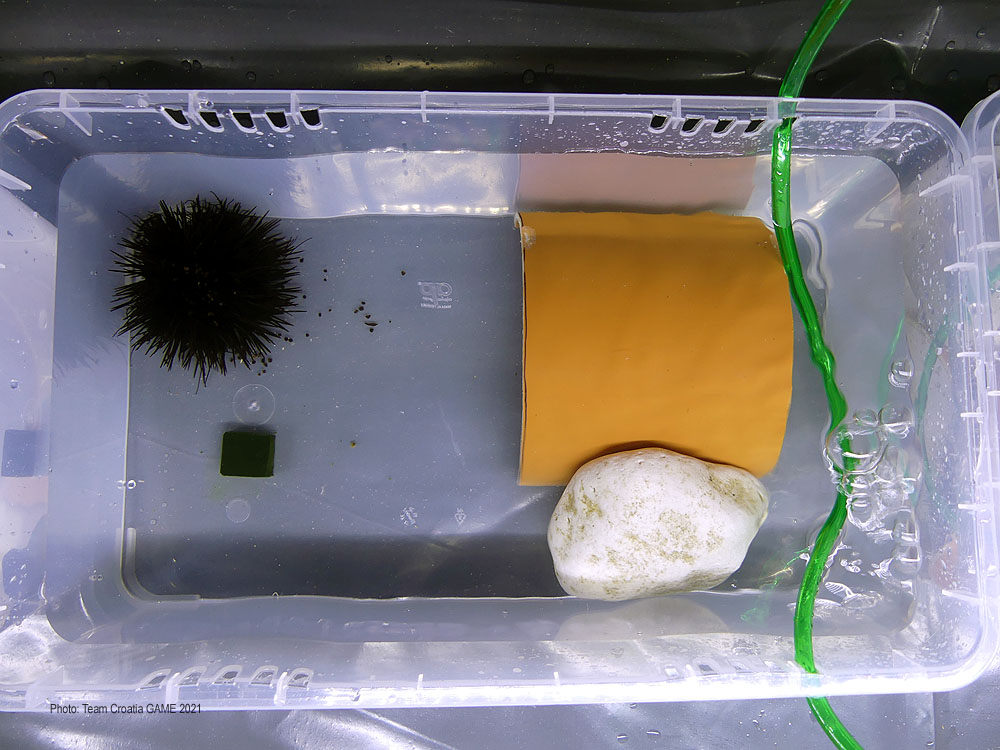

On site in Pula, we chose two typical sea urchins of the Mediterranean, Paracentrotus lividus and Arbacia lixula, and the snail Cerithium vulgatum, as study organisms. Collecting sea urchins can be a bit of a challenge, since they are often firmly attached to the rocky ground and their spikes can easily break when too much force is used to detach them from the substratum. During our snorkeling trips at the collection site, we therefore carefully detached our specimens by hand. Fortunately, our third test animal, the snail Cerithium vulgatum, is a common inhabitant of the shallow subtidal, and thus quite easy to collect (if their shells are not inhabited otherwise – looking at you, hermit crabs).

Since it is the first time that Morska škola is participating in a GAME project, we had the exciting chance to build our laboratory set-up vastly from scratch. Gerwin was more than enthusiastic to provide us with all the lab space, tools and personal expertise that we could have possibly hoped for.

Building an experimental set-up is much like assembling IKEA furniture: You start by knowing what you‘re doing, then something doesn‘t work, so you take it apart again – and in the end, it works, but you‘re not entirely sure why. Seriously though, our set-up is actually quite simple. So, let us give you a short overview of what we have been tinkering together in the last couple of weeks.

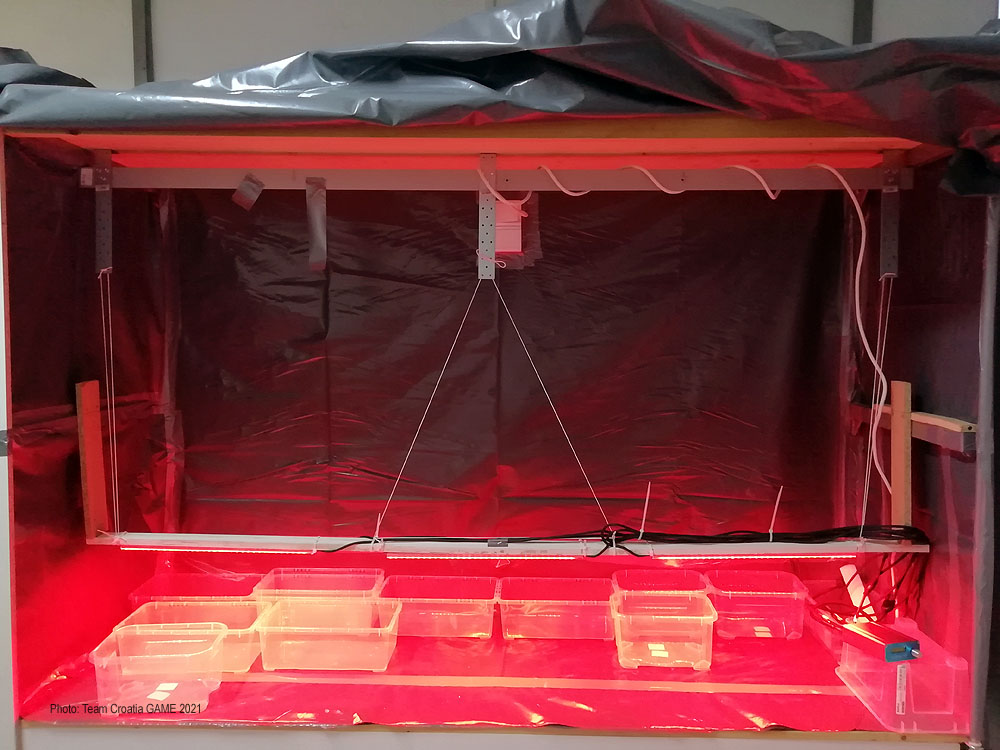

The most important thing for our set-up is to spatially separate the different light treatments, so that the experimental groups cannot influence each other. Luckily for us, our lab room already had a large shelf with three rows installed. We decided to use one shelf row per light treatment. We then enclosed the rows individually with light impermeable black foil, which we sealed with (lots and lots of) duct tape.

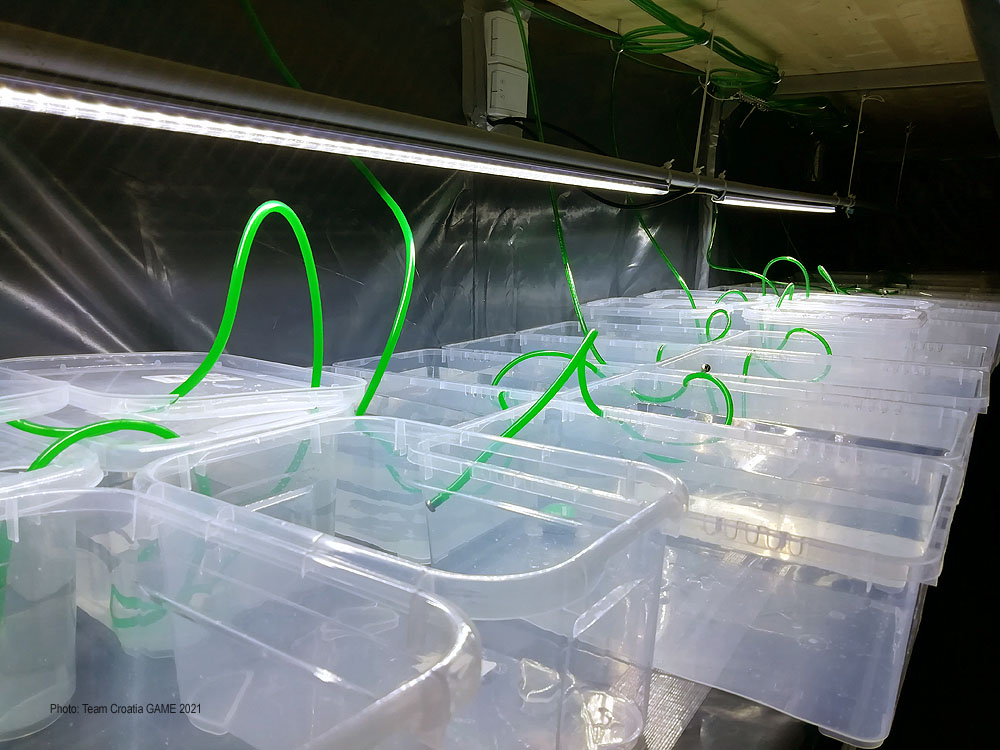

Having set up our shelves, we installed the aquaria. Aside from food, not much is needed to keep our sea urchins and snails happy in the laboratory – mostly just this: clean seawater and oxygen. To ensure good water quality, we installed a large header tank, which can be used for regular water exchanges. For a steady oxygen saturation in the aquaria, we put up an air pump with a distributor system.

Additionally, we decided to provide our test animals with shelters. Shelters are meant to make the experiments more realistic, since animals in their natural habitat can often avoid light pollution by hiding in shaded areas of the rocky shore. For our shelters, we used PVC pipes which we cut into dome-like „roofs“ with a jigsaw (no fingers lost, so far).

Lastly, we installed our LEDs and automatic light dimming system, ensuring that the animals are exposed to equal light intensities. To mimic the natural day-night rhythm, we programmed our dimmers to local sunrise and sunset times.

Once we had finished preparing our set-up, it was time to get our first animals into the lab. For the sampling, we picked a pristine (and very beautiful) beach on the shore of Stoja, Muzil bay. The bay sustains a high biodiversity of flora and fauna and is fully protected from light pollution – thus, perfect for our animal collection.

When sampling animals, it is important to work quickly in order to minimize stress. Thankfully, we found many committed helpers at Morska škola who assisted us during our collection trip. After two hours of snorkeling, we had found enough animals to run our pilot studies. But the hardest part was still ahead – the transport. To avoid stress, we put a maximum of five animals in one transport box and carefully drove them back to the lab. Upon arrival, we noticed that the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus had started spawning. Many enthusiastic water exchanges later, we were relieved that all animals survived.

To keep our animals well fed, we started to produce food pellets from agar and algae powder. After having tested more cooking recipes than Gordon Ramsay, we ultimately found the perfect formula that rewarded us with magnificent food pellets, made in Croatia™.

Most recently, we have started with our red light pilot studies. Purpose of the pilot study is to determine whether our species are insensitive to red light. This would allow us to use timelapse photography under red light conditions for our main experiments. For the pilot study, we have a simple experiment running for 24h: A control group experiences a day-night rhythm with simulated daylight during the day and darkness during the night. Meanwhile, the red light group experiences an identical day-night rhythm, however, with darkness substituted by dimmed red light. During the 24h period, we are providing the animals with food pellets to assess their feeding activity.

Beside the work, we also have some free time to appreciate the beauty of Istria. The historic city of Pula and surrounding areas offer a lot to see and do: ranging from an Roman amphitheatre to numerous nice beaches and caves. To enjoy the Mediterranean flair, we are going on snorkeling trips, dives and dolphin observation tours. In the meantime, the Croatian cuisine is keeping us in good spirits (truffle cheese, gelato and too much olive oil…) and we are looking forward to our remaining stay here in Croatia.

Ciao and sunny greetings from Pula,

Anamarija, Marie & Franz