So in this year’s Portugal GAME project, we are Joana from Lisbon, Portugal, and Katrin from Munich, Germany! We worked together on the beautiful island of Madeira and here is our tale of our time there!

Joana is a Marine Ecology Master who heard about this project from a former advisor in her favourite area – intertidal ecology – and Katrin is a Marine Biology Master’s student at Rostock University who took advantage of the great opportunity to compile and write her Master’s thesis within the GAME programme in experimental ecology.

We arrived in Madeira in early April and the first thing that struck us was the great weather – never too cold or too hot. The landscapes are also gorgeous and were completely new to both of us: For instance, within maybe half a kilometre from the shore you can reach several hundred metres in altitude and no matter how steep the slopes Madeira’s people built roads and houses right on the edges. The vegetation is incredibly dense and diverse, while most of it was introduced by the first explorers of the island. This made Madeira become the “Flower Island” because all year round plants blossom beautifully in all colours you can imagine – and locals eagerly take advantage of this richness in their many “festas” (local festivities).

During our first days at the Canning-Clode Marine Laboratory (a research group at MARE – Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre; check www.canning-clode.com) we got to know the international team there, who were immensely helpful, motivated and who genuinely love what they do. Our mentor was João Canning-Clode, but quite often we also got precious help from Ignacio, Sole, Patrício and Susi (the last two are both former GAMiEs – same as our boss!).

Our mission, which we developed during the GAME planning phase in Kiel in March, was first and foremost to assess the feeding behaviour of a local marine grazer (= algae-eater) at different water temperatures. Second, if possible, expose a local alga, which serves as a natural food source for the grazer, to similar temperatures and measure its growth. Thirdly – ideally – to test if algal growth changes when grazing pressure is induced.

We started by making a plan about which grazer and algal species to look at. This sounds easier than it was, because the waters of Madeira are characterized by very low nutrient concentrations. Hence, there are hardly any macroalgae around and as a consequence not many herbivore species as well – let alone in abundant numbers. Nevertheless, we went to a couple of beaches that had intertidal rock pools to look for possible “candidates” and we went snorkelling to include subtidal areas in our investigations.

After much back and forth, decision-making and confusion we finally settled on two species of local sea urchins – the ‘Black sea urchin’ Arbacia lixula (left picture below) and the colourful ‘Rock sea urchin’ Paracentrotus lividus (right picture below).

We started with running some pilot studies to see how the urchins do under the laboratory settings and conditions. This was also done to get a feeling for what kind of algae they like, how much oxygen they need, how an happy sea urchin looks like (spines erect, ambulacral feet happily trawling through the water) or what should be interpreted as alarm signals (e.g. flat spines, discarding spines, spawning, or not attaching themselves to the container anymore).

It turned out that they were not the easiest animals to handle in the lab – not just because their spines are actually spiky and can prick through human skin if you hit them in the right angle, but because they are somewhat picky eaters. Furthermore, the first time one of them spawned we were sure it had died overnight! The thousands of tiny, dark red eggs looked like a bloodbath inside that bucket! But after a while at least the colourful rock sea urchins seemed to be quite content in the lab.

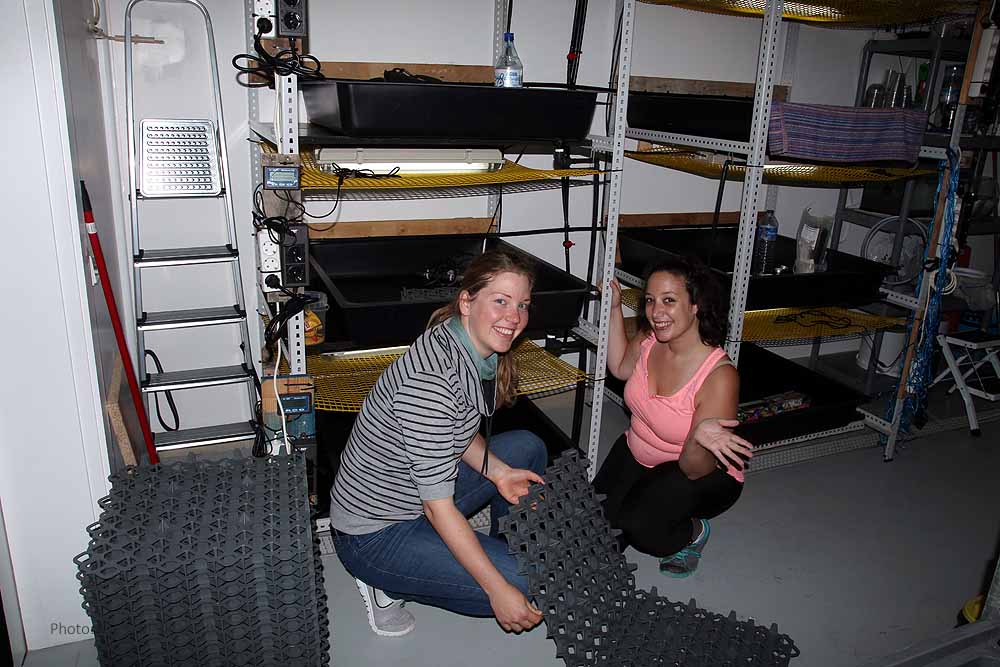

Meanwhile we had also begun to order the missing equipment and consumables we needed for the first part of our experiment. Because our lab had only recently moved to its current location and was still very (!) empty, we pretty much had to start from scratch. We started off with 6 empty shelves for which we neither had fitting waterbaths nor adequate buckets for keeping the urchins, let alone water or air supply. To provide fresh seawater and aeration to our animals, we had to acquire a lot of tubing and flow regulators and we had to build a water distribution system to get the water to the different shelf levels. Quite soon we realised that it would be impossible for us to produce our own dry algal material for the feeding assays, because there are simply not enough green algae in the waters of Madeira. Therefore, we started chasing down people worldwide that might sell us Ulva sp. powder…

Now, keep in mind that we were on an island, which is 1hour and 30 minutes by plane away from mainland Portugal. There is no regular ferry connection and airplane landings depend on the wind conditions. Therefore things can take veeeery long to reach Madeira and our material needed 2 months to arrive – from the moment we issued the first order until the last item arrived. The things that were the fastest to arrive – sometimes within the same week! – were those we ordered from Amazon such as the agar powder for the urchin feed. But some things that we ordered from Spain (the urchins buckets)…oh dear…Katrin was about to lose her nerves and Joana – who’s the Portuguese type of chill and should be used to this by now – wasn’t that far behind.

Luckily all things finally arrived! And you can’t imagine how relieved we were when even the lab’s precision scale arrived too – and the drying oven! However, time had been severely cut short (only four months left!) and therefore the algae growth and the grazer-algae interaction part of our experiment were compromised. But this was alright, since we had juuuust enough time to surely do the grazer part… right??

Unfortunately, some more promiscuous circumstances slowed us down further. One was that the local plumber, who had done most construction works in the laboratory’s wet lab, was so popular because of his decent work that everyone else wanted him to do things and so he didn’t find the time to finish the water supply system we needed. After Katrin finally learned the lesson that Portuguese time estimates (“tomorrow”, “next week”) should not be received with German punctuality, we at last got the “OK” from our boss to improvise our water supply ourselves. Enthusiastically, we were just about to put our set-up to life, when… the lab was closed for a couple of days due to construction works on the rocky hill right behind it. Luckily, the rock that indeed came down during these construction works crushed into the next door office and storage room but not into our lab… Puh! Some days after that, we finally managed to come back to the lab safely and completed the set-up in a few very intense working days.

However, a week and a half before we wanted to begin with our experiments, we discovered that salinity in the lab was too low due to a freshwater source near the intake location of the seawater pipeline. Who would have thought about that?!? This was complicated to solve in such a short time but flexible as we had become, we changed the water supply system for our urchins from a constant low-rate flow-through to a semi-flow-through. For this, we opened the outlet valves of the supply system manually twice a day to replace the water in each urchin bucket by water that came from storage tanks and not from the sea. We filled up these tanks manually every second day using a water pump that we deployed in the ocean. So, fun fact time: If your water pump is not strong enough to pull water quite a few meters upwards and is not adapted somehow to deal with saltwater, be prepared to bust up a couple of water pumps!

2 ½ months after our arrival at Madeira we finally got started with the first of the grazer experiments… and all 180 urchins died/were dying within the same week. It turned out that the long transportation was far too stressful for the urchins, especially for the black ones – unless you put very few of them together in a well-oxygenated bucket. Hence, instead of getting them all from the faraway place in Funchal, where both species are well accessible because they live in rock pools, we got Joana’s rock sea urchins from the small beach near the lab, while Katrin’s black sea urchins were collected by apnoea diving (we needed more than 100 individuals!) in the subtidal next to it. We had to take urchins into the lab in excess so we could narrow in the size range of the animals we wanted used in the experiments. So the first thing we did with all candidates was measuring and weighing them before we distributed them into the single urchin containers. Due to restraints in lab space we divided our experiment into two halves that were conducted one after the other. This allowed us to realize more temperature regimes. Our first half started at the end of June, the second in the beginning of August.

The experiment – once it started for real – actually went very well considering the initial difficulties. Katrin still had some trouble with her urchin species Arbacia lixula. They showed increasing mortality rates even before they reached the targeted temperatures and we could not figure out why this was the case. At some point she made the best of it and started collecting their beautiful coronas.

During the course of the experiment that consisted of (a) acclimatisation to lab conditions, (b) acclimatisation to the targeted temperatures and (c) final feeding tests we checked our animals every day, exchanged the water, took notes, made sure the aeration tubes hadn’t popped out and elevated the temperature in small steps. We also solved another conundrum: We learned from a GEOMAR recipe how we were supposed to produce our urchin food. We planned to make pellets out of agar and Ulva powder, but we did not manage to get the consistency right! There’s a lot of science behind how to cook and when to stir agar in the microwave, but eventually, of course, we mastered the art of pellet making.

During our experiment, luckily the busy plumber found time to solve our lab salinity problem, so from August on our storage tanks were refilled automatically. How wonderful it will be for the next GAME generation to come and work at Madeira, when everything is in place already! 😛 We at least would go back very happily now!

But not all was work! We had fun with our team and can certainly say that we have good friends and colleagues in them. At lunchtime it was always funny to listen to the Portuguese and Spanish fighting about who makes the right paella or the Italian giving us introductions into REAL pasta and pizza. Past and still-to-come diving tasks and adventures were shared and compared, while, during the release of the latest Game of Thrones season, you sometimes would find people leaving heated discussions – either with a strange annoyed-amused look in their face or loudly singing with the fingers popped into their ears to avoid any spoilers. Every once in a while someone brought food for everyone which was much appreciated 😊

The people of Madeira are incredibly and genuinely nice and the landscape is absolutely impressive. We got to go around the island together and separately and we advise that you do the same. The food (if you’re not vegetarian) is delicious. For vegetarians, though, you can usually choose between a salad or fries or bolo do caco (traditional sweet potato bread with garlic butter). If you’re lucky, maybe you’ll find an omelette. If you’re very lucky, maybe even an omelette with mushrooms. But almost all year around there’s an incredible selection of yummy fruit available – on Madeira they grow bananas (a local type that is a bit smaller than usual and very fruity), avocados, persimmons, papayas, figs, melons, oranges, cactus fruit, multiple types of passion fruit, cherimoyas,….

Only two things are perhaps amiss in Madeira – almost all beaches are made of stones/rocks (only 3 have sand) and there are veeery few flat surfaces. Most of the island consists of humongous hills and you’ll likely do quite a bit of hiking, whether you intend to or not (haha!).